Fresh burials in Westbury Park Cemetery in Johannesburg, South Africa, on Thursday, June 24, 2021. With Africas most developed nation recording one of the worlds fastest pace of deaths from Covid-19 infections, large swathes of the country are being deluged with offers of burial insurance. Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Thousands of bodies are waiting at the government mortuary while families beg for them to be returned to be buried. The bodies are decomposed, burned beyond recognition, or are the remains of victims of crimes. They lie in the morgue like hostages as the police DNA backlog grows.

In 2019 Felicia Ndlovu went missing. Her family searched for her. They reported her missing at the local police station, but there were no leads. Three months later, as the police were investigating three other women who had also gone missing in the area, Felicia’s body was found.

She was murdered and buried in a shallow grave together with four other young women three years ago.

Kenneth Shabangu from Masoyi near White River talks about the pain his family goes through as they wait for the body of his 21-year-old niece Felicia.

“It has been three years. We can’t do any rituals for her. She is in a government mortuary, cold and alone, not with her ancestors. Three years.”

Desperate families in Mpumalanga have now approached the president of the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa (Contralesa), Chief Mathupa Mokoena, the South African Human Rights Commission and the South African Council of Churches to intervene after numerous requests to the police.

The letter, dated January 2022 and which the Mail & Guardian has seen, is not long but it is emotionally charged. In it, families express their pain as they explain why they are looking for intervention.

“We are writing to you to ask for your help regarding the remains of our family members who have been in the government mortuary for a long time. They were killed by the criminals and their bodies could hardly be recognised even though we have managed to identify them. The South African Police Service (SAPS) has been refusing to release the remains on the grounds that they had been waiting for the results of the DNA. We are asking for your intervention. As community leaders and influential people, we believe that you can also try to assist us.”

The chief then met the two families who authored the letter. He told the M&G it was a difficult meeting.

“It pained me to see these families broken and pleading. I felt I had to do something. Keeping bodies in the morgue for such long periods of time is not African. There are rituals that must be done to ensure the people find peace. This can’t be done waiting for years to bury a loved one.”

The M&G contacted the SAPS provincial offices on several occasions but all questions were referred to the national office, which failed to respond to them despite undertaking to do so.

Last year, in March, Police Minister Bheki Cele and his management team conceded to parliament’s police portfolio committee that there was a serious backlog in DNA test results. They apologised and promised to improve. The backlog has negatively affected the work of the police, courts, victims of crime and their relatives as DNA evidence plays a vital role in many criminal cases.

Thousands of families across the country are affected.

The family of Sphamandla Khumalo, 33, who died when an inferno destroyed the Malacca Road informal settlement in Durban North, waited for more than a year to bury him.

The family of Linah Madonsela, who was killed with five other people when a Putco bus caught fire in Moloto Road just outside Pretoria in May last year, are still waiting for police to release her body.

Felicia’s family adds to the list. Distraught, her uncle, Shabangu, lays out a macabre tale of how the family was told that Felicia’s body would be released to the family in two weeks.

“We bought a cow preparing for the funeral.”

But months passed. Felicia’s grandmother, who had raised and adored her, was beset with worry. When she died, the cow, bought months ago, was used for the grandmother’s funeral instead.

“The fact that Felicia’s body had been kept in the mortuary for such a long time caused her granny some complications, which led to her death. They were best friends.

“As a family, we are worried about this situation, because we no longer believe that her remains will be released. We tried and failed to convince the police to speed up the process and nobody communicated with us,” Shabangu said.

As Felicia’s body languishes in the state mortuary the trial of her alleged killer continues to crawl. Julius Thabiso Mndawe appeared before the Mpumalanga highourt this week where he pleaded guilty to five counts of murder and five counts of defeating the ends of justice. The state has rejected this plea, which is based on his account that all the murders, including that of Felicia, were committed on the spur of the moment.

Mndawe’s list of charges stem from alleged crimes committed between March 2018 to May 2019. According to the National Prosecuting Authority, all victims were reported missing by their families, and all had connections with the accused.

“They were later found buried in the shallow graves in Numbi Trust, at the accused’s place of residence.”

Another family, the Mametje clan from Bushbuckridge, has approached the authorities with a similar tale of woe. Their 31-year-old son Given Shabangu’s (who is not related to Kenneth) remains were only released at the end of January after Chief Mokoena confronted the police after the families wrote to him. Shabangu was killed and burnt by criminals in Marite, Bushbuckridge in January 2020 and his body had been in the morgue for two years.

Rose Mametje explains how her son Given Shabangu was murdered and burnt by criminals in Marite, Bushbuckridge, in Mpumalanga. After waiting more than two years, Mametje finally received the body of her son a few days ago after Chief Mathupa Mokoena, who is the president of the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa (Contralesa) intervened and pushed the police to redo DNA tests

Rose Mametje explains how her son Given Shabangu was murdered and burnt by criminals in Marite, Bushbuckridge, in Mpumalanga. After waiting more than two years, Mametje finally received the body of her son a few days ago after Chief Mathupa Mokoena, who is the president of the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa (Contralesa) intervened and pushed the police to redo DNA tests“After we contacted Chief Mokoena the police came and took some blood samples and promised that they would release the body. Last week the remains were released and this weekend we are going to bury my son,” said Given’s mother Rose Mametje. He was finally due to be buried on Thursday, 3 February.

The family is now looking to find closure. “I would like to thank Chief Mokoena, the human rights journalist, the Human Rights Commission and others for assisting us to force the police to release the body of my child. Now I am praying that other families who are also in a similar situation get the assistance. The chief was [horrified] when we told him that we have been waiting to receive my son’s body for more than two years,” Mametje said.

During the parliamentary debate in March last year, the police minister had said the delays could be attributed to several reasons, including “budgetary allocations, contracts management and the shortage of DNA consumables, which are very critical [to] DNA sampling in our forensic laboratories”.

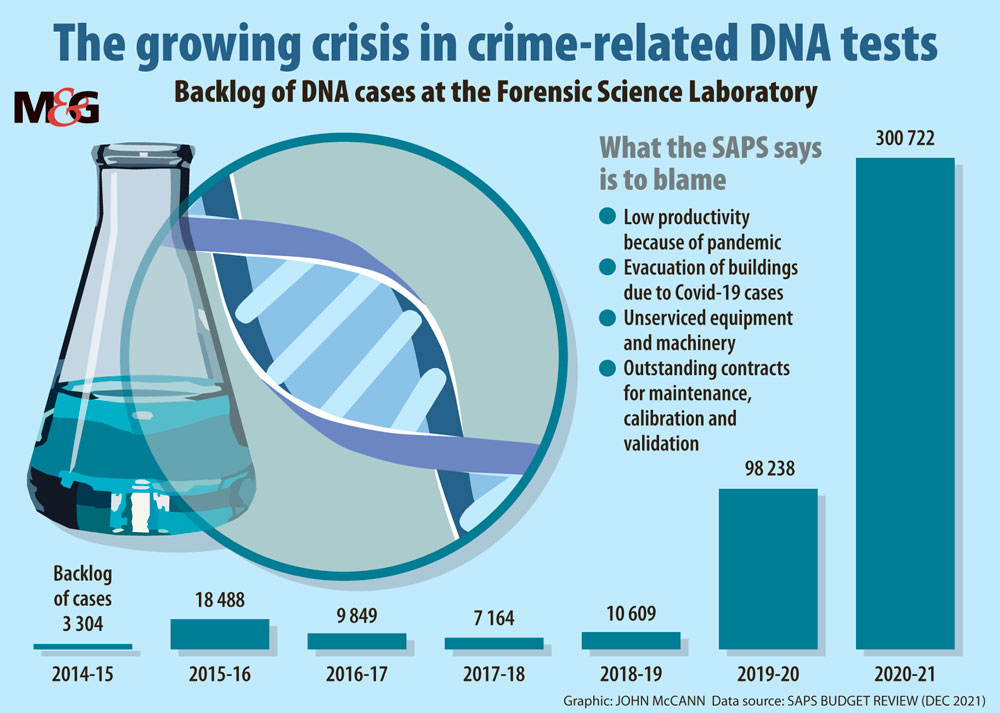

At the time, Cele said the backlog at the labs stood at 208 291 cases.

In the SAPS’s budget review the portfolio committee noted that at the end of the 2020-21 financial year the Forensic Science Laboratory had 300 722 cases that were yet to be finalised. The backlog increased from 27% to 84%.

This surpasses the international norm of 10% by 74%.

“According to the SAPS, the backlog had a negative impact on the criminal justice system, particularly with the detection and conviction rates,” reads the report.

The SAPS did not achieve its performance targets for improving detection rates for contact crimes and crimes against women and children that year.

Furthermore, the SAPS annual report states: “The increased backlog has unfortunately negated the incremental investment made by the South African government, during the period 2010-11 to 2017-18, to improve the efficiency of the criminal justice system.”

Families have asked the Congress of Traditional Leaders and the Human Rights Commission to intervene after waiting years to bury their loved ones. (Photo by GUILLEM SARTORIO / AFP)

Families have asked the Congress of Traditional Leaders and the Human Rights Commission to intervene after waiting years to bury their loved ones. (Photo by GUILLEM SARTORIO / AFP)

The committee noted that although the pandemic can be blamed as one of the reasons for the decline in performance during 2020-21, “the significant decline in the Forensic Science Laboratory environment started long before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Worryingly is the latter two reasons, namely non-operational equipment and machinery due to outstanding service and outstanding contracts for maintenance, calibration and validation of the equipment.”

Chief Mokeona is meanwhile pleading with the SAPS to fix these problems.

“My heart is bleeding when I see the parents crying to be given a chance to bury their children. It is so unfair to families because their children died a painful death and they were supposed to be [able to forget] what happened to them. I am still waiting for other families to come and see me so that we can also see what we can do,” Mokoena added.

[/membership]