8 September 2021: Clothes hang to dry at the Nancefield Hostel in Klipspruit, Soweto. (Oupa Nkosi)

Celumusa Dlamini grew up in an impoverished home in Emangweni village in Ladysmith, KwaZulu-Natal. His childhood dream was to become a taxi driver. In 2016, he packed his bags and travelled more than 475km to the City of Gold in search of economic opportunities, where he moved into the Nancefield Hostel in Soweto.

A businessman from his village who owned a fleet of taxis and some goats at the hostel had organised him a job. “The deal was that I would look after his goats for two years and after that ubab’ uMbuyisa would take me to the driving school to get my licence,” said the 25-year-old. Mbuyisa took care of Dlamini’s accommodation and food while he looked after the goats.

Two years passed and Dlamini now works as a taxi driver, driving the local route from Kliptown to the Bara taxi rank. He also helps intern Kwanda Dlangalala, 24, who also comes from Emangweni village, through the same process.

Dlamini considers himself lucky. His dream has come true, whereas many others who live at the hostel, who came to the city hoping for a better life have given up on finding a job. “I’m grateful to be able to send money home to my parents and also be able to save some for rainy days,” he said.

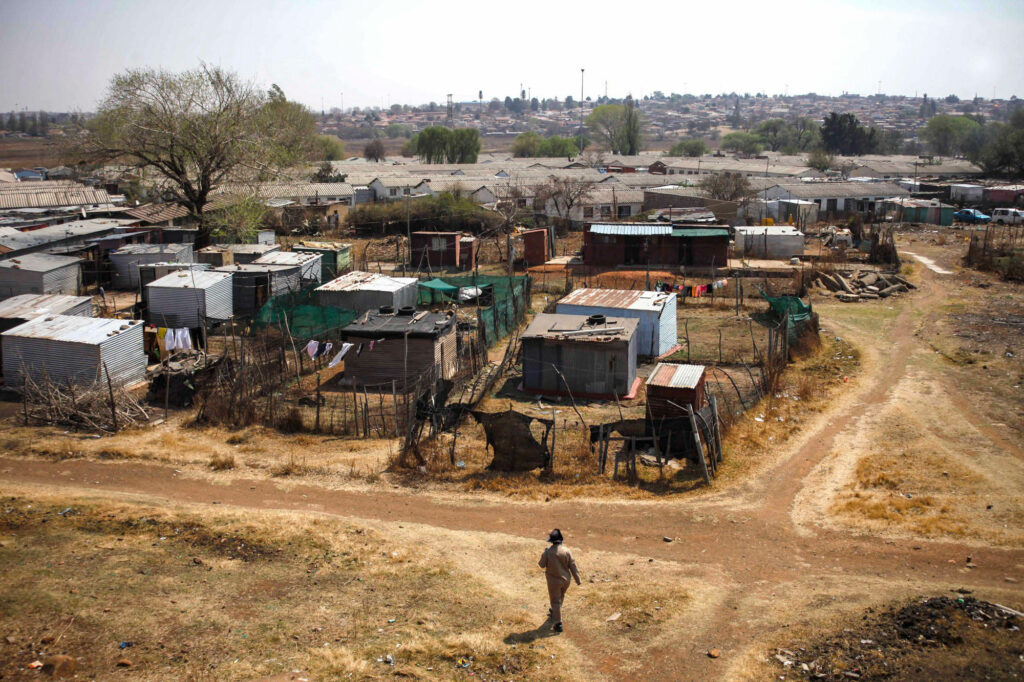

6 September 2021: Nancefield Hostel with shacks in the foreground in Klipspruit, Soweto. (Oupa Nkosi)

6 September 2021: Nancefield Hostel with shacks in the foreground in Klipspruit, Soweto. (Oupa Nkosi)

The establishment of hostels

Hostels in South Africa were built in townships designated as African residential areas during apartheid, located far from the cities and towns where white people lived. These transit camps offered affordable accommodation for impoverished migrant workers who lived in rural areas.

The hostel dwellers were never properly integrated into township life. Their wives or partners and children were not allowed to visit them, resulting in children being raised by their mothers, grandparents or members of their extended families.

Twenty-eight years after democracy, the Nancefield Hostel, which was built in 1958, is old and dilapidated — like many hostels. The view from the Maponya Mall down Moroka Nancefield Road is one of shacks, their density hiding the gigantic old dormitory blocks of the hostel. The structures are cracked and some have fallen apart, posing a danger to the occupants. Most broken windows are covered with flattened cardboard boxes to block out dust or the cold wind in winter.

Despite being banned in 2008, broken asbestos roofing sheets still top all the buildings. Streets are untarred, except for a few main roads that take you in and out of the hostel. Laundry hangs on makeshift lines strung from tree to building.

The showers in the old blocks still don’t have geysers and residents have to boil water on their stoves to wash, although constant power cuts make this impossible at times.

A mobile clinic visits on Mondays and Wednesdays to provide healthcare services. Recreational facilities for children are still not available and goats feed on stagnant spilled sewage that runs in the streets.

8 September 2021: Philile Zikalala, 38, started the first creche at the Nancefield Hostel in 2017, but was forced to close when Covid-19 hit. She used to provide food for each child no matter what their parents could afford. (Oupa Nkosi)

8 September 2021: Philile Zikalala, 38, started the first creche at the Nancefield Hostel in 2017, but was forced to close when Covid-19 hit. She used to provide food for each child no matter what their parents could afford. (Oupa Nkosi)

Electricity issues

Thandiwe Zulu, 40, used to rent a room in Kagiso, Mogale City, before she lost her job seven years ago. Out of desperation, she moved in with her boyfriend at the hostel. “Life was wonderful and I felt welcomed here,” she said. Her pink dress brightens the dark room and her dynamic sense of humour makes the three women next to her giggle.

Their electricity mains box exploded in April 2021, and for seven months residents lived without power. The box was meant to supply a few blocks, but ended up supplying the many shacks that have been erected in and around the area.

Zulu points to the extension cable on the floor that leads to a two-plate stove where Mama Mntambo is cooking in the dingy open-plan kitchen and lounge. “We are now getting electricity from our block 23 neighbours and we take turns to cook, cool our fridges and light our rooms.”

“I spoke to people from Eskom, [saying] that they should fix the electricity. They did not come,” said Mashiya “Thisha” Shange, an induna at the hostel. The box was fixed only in December.

Sharing is caring: Thandiwe Zulu, who lives in Nancefield hostel, had no electricity for seven months last year after the mains box exploded. She now accesses electricity from a neighbour. (Oupa Nkosi)

Sharing is caring: Thandiwe Zulu, who lives in Nancefield hostel, had no electricity for seven months last year after the mains box exploded. She now accesses electricity from a neighbour. (Oupa Nkosi)

Not the only problem

Crime is another scourge. The hostel’s notoriety goes back to the 1990s, when killings intensified, creating perpetual tension between the township residents living in the surrounding areas. “It was perceived back then that the hostels were for the IFP [Inkatha Freedom Party] and the townships were for the ANC people,” said Shange, who has held his position for more than 20 years.

In May last year, four cars were burnt and a 45-year-old woman was reported to have been gang-raped by three men during a protest about lack of electricity. “To be honest, as a leader, I got hold of that information and thus far there has been no one or woman that has come to confront me about this issue,” Shange said.

According to The Herald, another woman was raped in 2019. Two men were shot and killed in 2020 while sitting inside a taxi association patrol vehicle. And six dead bodies were discovered in a field in 2007. “I tell people to honour and respect people. It does not matter if you are Venda, Xhosa, Tsonga, Tswana or Pedi,” Shange said, reflecting on the diverse community that lives at the hostel.

Restoration efforts

There is a glimmer of hope that the hostel is changing. Mlungisi Mabaso, the City of Johannesburg’s MMC for housing, is on a mission to improve the living conditions at hostels, undertake refurbishments and create jobs. The 31-year-old protested successfully against the proposed demolition of the Dube Hostel in 2017, where he once lived for nine years.

The City’s social housing company has invested R178-million in a project that aims to revamp the old administration office and create cleaning and maintenance jobs for 18 months from May 2021 to November 2022.

The Gauteng department of human settlements spent R230-million building new apartments in Meadowlands, Mzimhlophe, Dube and Diepkloof. The flats were completed between 2011 and 2012, but left unoccupied and some were vandalised because of a rent payment misunderstanding between the department and residents.

“We are working hard on all our projects aimed at hostel redevelopment. As things stand, it is currently not at the level of satisfaction that I would like. We are, however, attending to all issues of repairs and maintenance in all the hostels that are under our management,” Mabaso said.

Born and raised in Ulundi, KwaZulu-Natal, the Inkatha Freedom Party councillor is popularly known among his peers as “Last Born”, because he is one of the youngest MMCs. He served as a community leader for eight years at Dube Hostel before rising to prominence, and attributes his success to his willingness to help people.

Proud of the changes

8 September 2021: Nomvula “MaRadebe” Dyanti, 52, has lived at the Nancefield Hostel for 27 years. (Oupa Nkosi)

8 September 2021: Nomvula “MaRadebe” Dyanti, 52, has lived at the Nancefield Hostel for 27 years. (Oupa Nkosi)

“When I arrived here 15 years ago, the hostel was dirty, buildings were collapsing and sewage from burst pipes would be all over the streets,” said Philile Zikalala, 38, who is proud of the changes Mabaso has wrought.

Zikalala used to run the Philile Early Learning Site, which hosted 23 children and employed two staff members before it closed down in 2020. It was the first and only educational institution at the hostel.

“I love kids. I feel blessed when I’m around them. They make me forget about my problems,” she said.

Nomvula “MaRadebe” Dyanti, 52, grew up during apartheid in a family of strong ANC supporters in White City. Dyanti had always wanted her own home and recounts the difficulties she experienced moving from room to room, renting with her husband before they found an affordable place at the hostel in 1993.

She applied for an RDP house several times, but was unsuccessful.

Minister of Human Settlements Mmamoloko Kubayi told the media the database for RDP houses was so flawed that the department could not tell who had exited the programme or not been allocated homes, and that the backlog could be much higher than the estimated 2.5-million houses. The department admitted its budget is constricted and that the influx of people into the city has worsened the housing problem.

This is an edited version of a New Frame story first published on 5 April 2022.