(MARCUS YAM / LOS ANGELES TIMES)

During the 2024 medium term budget policy statement on 30 October, the government of national unity (GNU) re-emphasised its commitment to “attracting more foreign investment”.

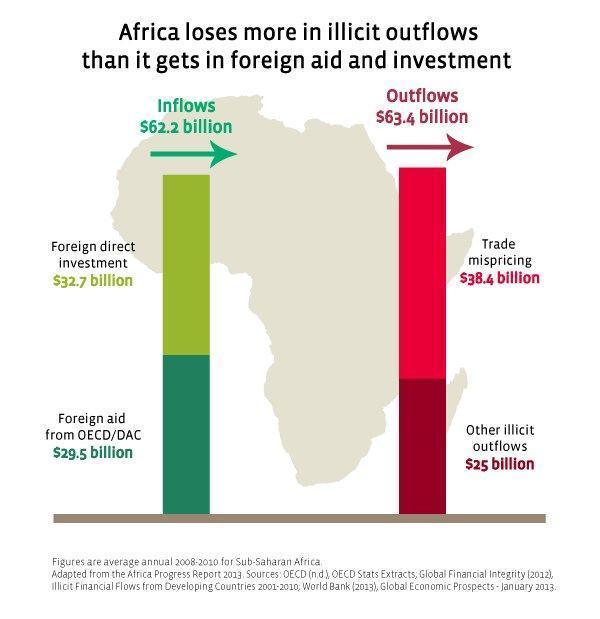

The latest iteration of the worn-out “investor-friendly” mantra is a desperate attempt to lure foreign capital into South Africa. Yet, history has shown that this strategy is a mirage, promising prosperity while delivering little.

The case of Samancor, the second-biggest chrome mining company in the world, is a stark reminder of the predatory nature of unchecked foreign investment.

While “investor-friendly” policies might temporarily attract foreign capital, they have not been found to result in investments that further developmental goals, create long-term economic growth and/ or result in improved social equity.

The story of Samancor Chrome is a textbook case of how “investor-friendly” policymaking has enabled corporate plunder, at the cost of long-term development.

Once a South African-owned industrial powerhouse, Samancor was allegedly stripped of its profits by foreign entities through a web of financial arrangements.

According to an ongoing case lodged by the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), along with the Alternative Information and Development Centre and a whistleblower ex-director, R7.5 billion was syphoned out of the country over the course of just 4 years. This deprived the state of vital tax revenue, workers’ and community trusts of income, and the nation of a valuable asset.

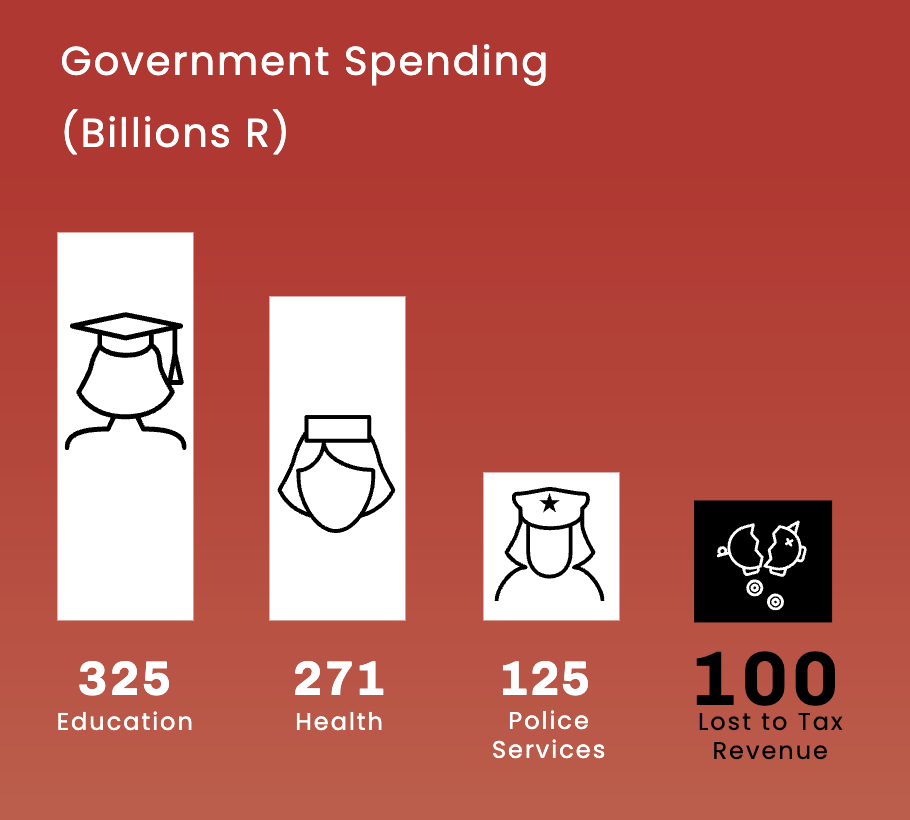

The amount of wealth lost to profit shifting and illicit financial flows is staggering. Estimates suggest the total level of illicit financial flows amounts to 4% of South Africa’s GDP (roughly R300 billion) every year, while every year R100 billion is lost to tax revenues alone. This is almost equivalent to the entire government budget for police services or more than a third of the health budget.

* source: National Treasury 2024-25 Budget, authors’ calculations.

The looting of Samancor

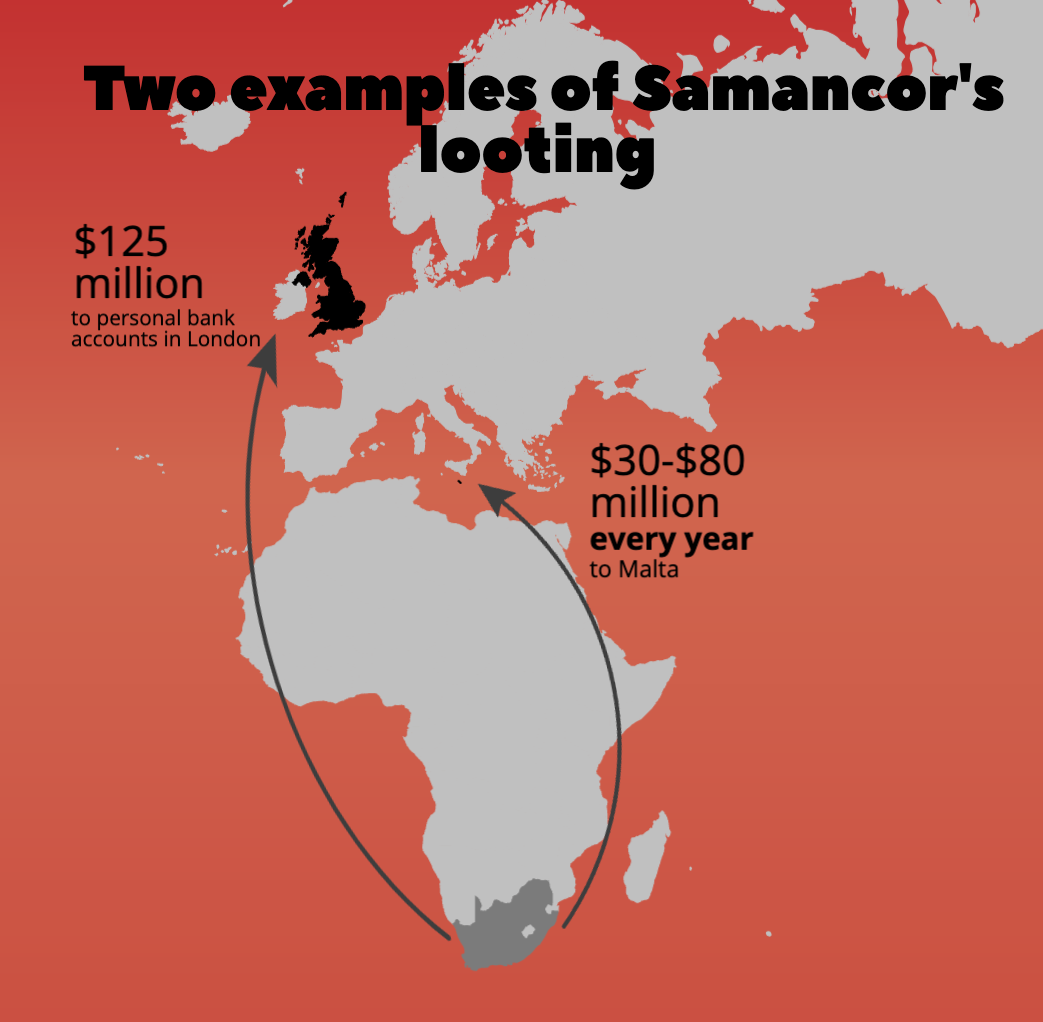

One of the core allegations against Samancor involves the establishment of a Malta-based subsidiary, Samchrome.

AMCU contends that Samchrome was a mere conduit for syphoning profits out of South Africa. The company allegedly generated exorbitant commissions with no value added, funnelling billions of rand to offshore entities with almost no corporate taxes, controlled by Samancor’s directors.

Another allegation involves the sale of a 50% stake in a Samancor subsidiary, Tubatse, to Sinosteel, a Chinese company.

The deputy minister of foreign affairs at the time, Aziz Pahad, proudly announced that “it was confirmed that the Chinese parastatal company Sinosteel was committed to investing $230 million (R1,7 billion) in a ferrochrome mine and smelter project with South Africa’s Samancor”.

However, Samancor’s 2008 annual report only reflects $100 million received in the books. The remaining $125 million was diverted to offshore accounts controlled by Samancor’s majority shareholder, Kermas.

This incredible affair is corroborated in email exchanges cited in the whistleblower’s affidavit. Nedbank Capital says that they “received $25 million and $75 million, by order of Sinosteel”. In a later email they say that they “can also confirm that Nedbank London has received $125 million on the account for Kermas”.

This illustrates how foreign investment often does not deliver the promised benefits and raises the question of how such a significant discrepancy could have gone unnoticed.

Given the high-profile nature of the transaction, it’s perplexing that entities like the accountants (KPMG), the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, the South African Revenue Service, the treasury and even Nedbank were seemingly unaware of the discrepancy between the publicised sale price and the actual amount received by Samancor.

This case underscores the importance of increased transparency and accountability for companies, particularly large corporations. Mandating the public disclosure of financial records for companies could help prevent such instances of corporate malfeasance.

It’s not just about lost taxes: wage evasion

The effect on South Africa extends beyond lost tax revenue. The diversion of funds from Samancor deprived the company’s workers of potential wage increases and undermined the company’s ability to fulfil its social labour plan obligations.

In a supporting affidavit to the court, AIDC called this behaviour of profit shifting and subsequent wage reduction “wage evasion”. Research on Lonmin as a part of the Marikana Commission found that profit shifting was directly linked to the illusion that the firm could not afford the wage increases that the rock drill operators were requesting. This highlights the direct impact of these practices on workers’ livelihoods.

The court ordered an independent assessment of the allegations against Samancor, which was conducted by BDO.

Samancor has claimed that the outcomes of the report show that no action is necessary. However, they have declined to share the report with AMCU, claiming that they are not obliged to under section 165.

AMCU disputes this, arguing that because section 165 allows for further recourse if such an investigation was argued to be irrational or incomplete, this right would be meaningless if they were not able to assess the results of that investigation themselves.

A court hearing on 5 November was to determine whether AMCU can access the report. A judgment is expected in early 2025.

This case of profit shifting at Samancor could be a watershed moment in South African corporate history. It marks the first time a trade union has launched such a high-stakes legal battle against a transnational corporation, demanding R1.5 billion in restitution for workers.

While unprecedented, it highlights the potential for unions to serve as corporate watchdogs. By demanding transparency around subsidiary finances and cross-border transactions during wage negotiations, unions can play a crucial role in preventing future corporate abuses.

The transformation of Samancor from a proudly South African company to a mere vehicle for foreign interests epitomises a troubling trend — the erosion of domestic control over what were once national assets.

Instead of thinking of illicit financial flow as resulting from the misbehaviour of a few “bad apples”, the state must look at how its larger-scale economic policy enables these flows and make changes where necessary. This includes reversing the Nineties relaxation of exchange and capital control and increasing reporting requirements for firms.

By prioritising the needs of its citizens over the profits of multinational corporations, South Africa can embark on a path towards a more equitable and prosperous future. The Samancor case is a stark reminder that the foreign investor-friendly model is a failed experiment. It is time for a radical departure from this destructive path.

Foreign investment as a threat to domestic development and sovereignty

The prioritisation of foreign investor-friendly policies speaks to removal of planning and controls, and the prioritisation of opportunities for profit-making, regardless of how they are linked or not linked to the rest of South Africa’s developmental goals, such as decreasing poverty, unemployment and inequality.

We cannot continue to view our developmental goals as benefits coming from growth rather than objectives on their own.

Chloé van Biljon and Jaco Oelofsen are programme officers at the Alternative Information and Development Centre. Further reading on the case can be found here: affidavits, court documents. This piece is also published in Amandla magazine.