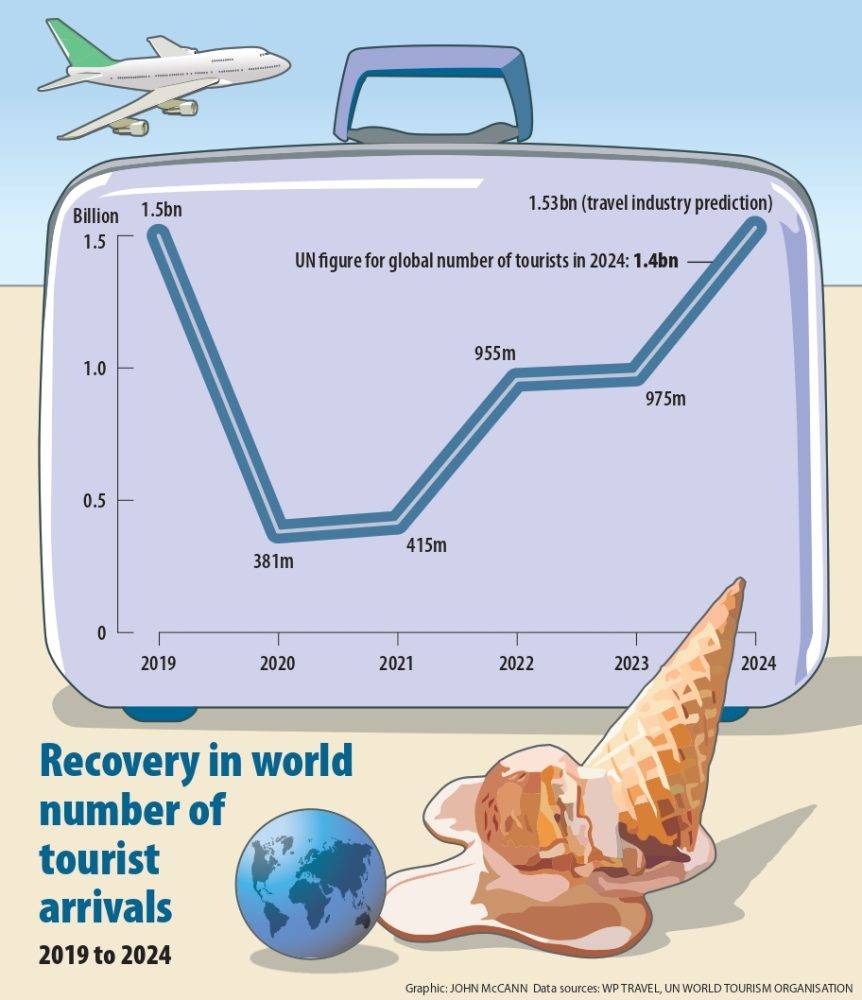

After the stall during 2020’s pandemic, travellers have come storming back exponentially each year

For almost the entirety of her existence, the idea of luxury travel was absurd to Homo sapiens. Fraught with danger, long-distance crossings were reserved for desperate migration in search of land and resources.

But 21st-century convenience has given birth to a new creature. His caricature is striped with tan lines, holds a vanilla ice cream cone dribbling into his beach flops and sports an ill-suited sun hat. Renowned for his slothfulness, he is sought-after for his foreign currency and insatiable desire to consume.

He is the tourist.

As meek as he appears, he is not innocuous. And he is far from inconsequential. For even on our planet — where we face unprecedented uncertainty and devastating conflicts — he may well have one of the biggest roles in the near-term shaping of our lives on a global scale.

After the stall during 2020’s Covid pandemic, travellers have come storming back exponentially each year. The United Nations World Tourism Organisation estimates that this culminated in 1.4 billion international tourists in 2024 — a return to the highs of 2019.

Those numbers are having a profound effect on our way of living in multiple ways. Whether directly or indirectly, our ubiquitous urge to travel has become a civil and geopolitical talking point.

A new resource

“My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his son will ride a camel.” — Commonly attributed to Dubai founding father Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, who warned of the need to diversify from oil more than 50 years ago.

No nation is likely to capture the headlines in this regard, this year and beyond, like Saudi Arabia.

There the promise of tourism will not just move mountains, it will cover them in snow in the middle of the desert. And that is precisely what must happen to prepare Saudi Arabia to host the 2029 Asian Winter Games. In 2022, it was selected to become the first Middle Eastern country to do so.

The games will take place in Trojena — a tourist destination centred around a ski resort that doesn’t yet exist (official estimates put its completion at 2026). While snow is not unheard of in the region’s upper peaks, artificial white frosting will undoubtedly have to be generated to keep the slopes open for skiing for the planned three months of the year.

That’s not easily done in a country with no natural rivers or lakes, necessitating the scalping of valleys to create cavernous reservoirs for water.

As divinely celestial as the project is in scope, it is only one limb of the Neom behemoth. Announced by ruler Mohammed bin Salman in 2017, Neom — a portmanteau of the Greek prefix for “new” and first letter of the Arabic word Mostaqbal, meaning “future” — is arguably the most ambitious (the pessimist would say ludicrous) megaproject in history.

While the new manufactured beaches, port and subterranean “upside-down skyscraper” are all stories in and of themselves, it is the audacity of The Line that has lured the most international attention. Envisioned to be the world’s first linear city, its final length — now pushed to 2045 — will be 170km. In April, Bloomberg reported that development is well behind schedule and only 300 000 people are expected to move in by 2030, significantly short of the 1.5-million resident target. The Kingdom has denied the lag.

The reason for this race to dystopia is not difficult to surmise. Our world is ostensibly going green — or at least its leaders are under exponential pressure to prove they are moving towards sustainability. With the halcyon days of unrepentant fossil fuel guzzling gone, Saudi Arabia, like most petro-economies, must diversify.

The United Arab Emirates, with its glossy skyscrapers (wholly unnecessary in a desert landscape), has proven the tourist path. Qatar has sought to follow, and now Saudi Arabia.

The problem for the latter is that it is carrying decades-old negative perceptions of repressive gender policies, a reputation for migrant labour abuse and the indelible stain of journalist Jamal Kashoggi’s dismemberment. The untold billions spent by Bin Salman on marquee sporting events — epitomised by the recent awarding of the 2034 Fifa World Cup — to scrub its image have earned the term “sportwashing” a prominent place in the modern lexicon.

There was loud international condemnation when the World Cup was hosted in Qatar in 2022, based on credible reports of inhumane labour conditions. With the hitherto unseen scale of tourist attraction efforts exponentially increasing across the oil-rich world, it will be one of the predominant issues not just of 2025, but the coming decade.

But these are not novel strategies. Kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko organised history’s most infamous act of sportwashing when he emptied the former Zaire’s coffers to lure George Foreman and Muhammad Ali to the Rumble in the Jungle in 1974.

Decades later, eastern neighbour Rwanda is investing heavily in attracting visitors; Premier League fans will know that “Visit Rwanda” has sponsored Arsenal, one of the biggest teams in the world, since 2018.

President Paul Kagame’s critics will tell you that this is an attempt to endear himself to Western sentiments in the hope that they will look past his strongman regime. As Michela Wrong, author of Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad, has written, Rwanda offers a pristine facade — tourists come for the gorillas, stay in cushy hotel rooms on clean streets, and forego any true experience approximate to that of a regular Rwandan.

That effort is doubled when world leaders are expected and the city is “transformed into a gleaming conference hub. The flowerbeds have been meticulously weeded, every kerb will have been freshly painted, there won’t be a homeless person in sight. But the explanation for that latter detail — before important get-togethers, the government relocates homeless people to ‘transit centres’ for ‘reeducation’.”

Kagame was re-elected last year by an unashamedly claimed and inconceivable 99.18%. Tourists must ask themselves if that is something they are comfortable with.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

No fun in the sun

Visitors to Barcelona last July were enjoying an early afternoon sangria when they were assailed with water pistols by nearly 3 000 protestors marching through the streets chanting “tourists go home” and “Barcelona is not for sale”.

Protests continued sporadically throughout Spain’s hotspots over the following months. One of the more creative guerilla actions saw protesters — exasperated by the disregard for water usage during a shortage — invade a hotel and wash their dishcloths in the swimming pool in front of bemused sunbathers.

While superficially humorous, the peaceful nature of these protests belie what is a boiling frustration. Annoyance with imposing visitors is nothing new but, as Nick Beake reported for the BBC: “This year it feels like something has changed. The anger among many locals is reaching a new level.”

The sentiment has spread to many of Europe’s other popular haunts such as Venice, Berlin and Greece. It has reached the extent that British tabloids are now guiding their readers on where to holiday; as typified by The Times headline: “Europe’s hostile holiday hotspots — and where to go instead”.

The anger has its roots in several factors. There is the primordial annoyance we all experience at having our living space invaded. On this point, the quality of tourists also matters a lot to a lot of people. Better to have aesthetes who will spend heavily at museums and restaurants, than British bachelor parties blazing through town on a cheap booze-fuelled bender. Some Barcelona bureaucrats are even toying with proposals that might close the tap on the latter and encourage the former.

But the kernel of the issue is that most universal of modern human complaints — the cost of living.

The tourist’s tendency to spend indiscriminately drives up rental prices, local goods and services. Add to this the rise of the digital nomad, another issue altogether, and residents begin to feel that their home is no longer built for them.

Arguably the biggest villain in this scenario is not our solitary tourist but tech giants such as Airbnb. Such platforms encourage financiers to scoop up property and set it up for holiday letting, eliminating rental options entirely.

‘Plague of locusts’

For all the simmering antipathy, there isn’t a consensus that these trends are wholly negative.

Many pundits are beguiled by the prospect of ever-increasing raw figures flowing into any given economy. Consider The Economist’s rebuttal in November, insisting “that noisy protesters in European cities are only a small minority”.

It wrote: “To take advantage of the economic opportunities tourism offers, cities blessed with visitors might want to avoid putting up barriers, and instead enhance their readiness to welcome travellers.”

The momentum, however, is carrying the continent in the opposite direction.

From a proposed fee to see Rome’s Trevi Fountain, to Amsterdam’s imminent move to redirect cruise ships away from its centre in an attempt to — as one local politician phrased it — limit the “plague of locusts” swarming into the city, tourist-mitigating policies are very real and are talking points that will probably only louden.

It’s not only Europe. Hawaii — the archetypal tourist destination — received prominent mainstream media attention last year for the disquiet brewing among many locals who must contend with 10 million visitors every year.

The Pacific island state has always relied on its substantial income from tourism — but is there a dollar too far?

That question is being asked more and more in our globalised zeitgeist. It’s only a matter of time until we get an answer.