Local government is approaching a critical crossroad after more than two decades of mismanagement. Municipalities are at the service delivery coalface. At this level of government, the citizens and voters deal directly with the government and local government is the face of government. At the general election in 2024, will the governing ANC be punished for its failure at the municipal level?

The total local government budget was R509-billion last year, approximately 25% of the total national government budget. If local government continues to fail to deliver, government in general, including national and provincial government, fails. Over the past two decades, the level of service delivery and the financial health of local government has deteriorated to a point where many analysts predict a system shutdown. Structural change is urgently required. The question is: Can the “local government boat” be turned towards a positive trajectory or will we continue on this downward spiral towards the collapse of local government as we know it?

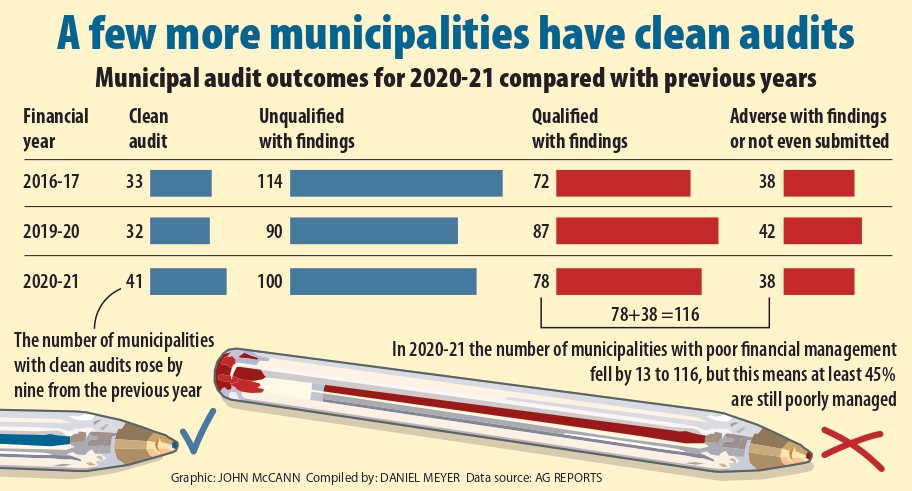

An important issue that needs to be taken into account is that long-term poor financial management ultimately leads to poor service delivery, therefore, it’s crucial to assess the state of financial management in municipalities. In the latest auditor general report on local government audit outcomes for 2020-21, released last month, the situation regarding financial management at most municipalities seemed dire.

There are 257 municipalities which include 205 local municipalities (with a total combined budget of R176-billion and an average annual budget of R860-million), 44 district municipalities (total combined budget of R35-billion and an average annual budget of R790-million) and 8 metro municipalities (combined budget of R247-billion and an average annual budget of R30.8-billion).

Regarding the equitable share, the local government receives an annual amount of about R135-billion from the national government. In contrast, provincial government receives an amount of R661-billion. The question should be asked: should local government not receive much higher financial support from the national government?

In Poland, the fastest-growing western economy, for example, local governments are allocated as much as 40% of personal tax collected in the municipal region, resulting in well-sourced and well-functioning municipalities. Local taxpayers are more willing to pay tax if it is spent in their area. This income is in addition to the normal rates and taxes collected.

In Poland, local independence and decentralised decision-making are important concepts. Meanwhile, in South Africa, municipalities are underfunded, taking into account their mandate, and are not sustainable. A total of 33 municipalities are currently under administration by the relevant provincial governments.

The main reasons for this dysfunctionality are poor financial management, lack of service delivery and lack of capable staff. In 2020-21, the auditor general found 185 material irregularities with a financial loss of R3.9-billion, including the VBS Bank case.

It might be asked if the provincial government could step in and manage the growing number of dysfunctional municipalities. The answer is, in most cases, “no”, due to the lack of provincial government capacity and the highly political environments in municipalities. In many instances, the appointed administrators are consultants and appointed at huge cost.

The table on this page summarises the auditor general audit outcomes for 2020-21. Although the number of municipalities with clean audits has improved from 33 in 2016-17 to 41 in 2020-21, the number of municipalities with qualified audits, adverse audits and those municipalities that did not even submit audit reports increased to 116. This means at least 45% of municipalities have poor financial management. But another 100 municipalities also had unqualified audits with negative findings.

In terms of the capacity of financial departments at municipalities, chief financial officers are in the position for an average of 45 months, or just under four years, with 20% vacancy rates. They are usually appointed on five-year contracts and most do not complete these contracts.

The capacity of financial departments is generally lacking and cadre deployment has also affected these departments and other departments in municipalities. Consultants are usually contracted to assist with financial audit reporting at municipalities. In 2020-21, this accounted for R1.26-billion or R8.2-million a municipality. A total of 62% of municipalities appointed consultants for this purpose.

Consultants’ fees increased by 100% from 2019-20 to 2020-21. The total amount used for support was R11.7-billion. The auditor general found that only 28% of municipalities had proper financial record keeping, and the rest did not have the systems to compile quality financial statements.

Skills transfer also seems not to take place. Most municipalities that spend vast amounts – more than R20-million – on consultants for accounting and audit purposes did not achieve clean audits but poor outcomes from the audit process. The financial health of local government is of grave concern, with only 16% classified by the auditor general as in a good state, while the rest are in growing difficulties. Also, 28% of municipalities are in danger of short-term failure to continue as a going concern.

Further proof of financial mismanagement is that municipalities took, on average, 240 days to pay creditors. In comparison, the national government guideline is 30 days. Furthermore, municipalities owe Eskom approximately R55-billion and water boards a further R13-billion. The amounts are rising fast. A total of R1.96-billion was lost in 2020-21 due to fruitless and wasteful spending and 64% of municipalities incurred unauthorised expenditure of more than R20.5-billion. This means that money was spent but not budgeted for. By the end of last year, 47% of municipalities owed more than they had in the bank.

Municipalities are also not responding well to essential infrastructure spending on repair and maintenance. National government guidelines indicate that municipalities should allocate at least 8% of the total infrastructure asset value for this purpose, while only 3% is currently allocated, on average. More than 40% of municipalities only spend 1% on repair and maintenance.

Water losses are out of control. On average, 50% or R9.8-billion of water is lost annually due to old infrastructure and leakages. We can not afford to have any losses, considering the water provision crises across the country.

Another shocking statistic is that only 11% of the 257 municipalities complied with supply-chain management legislation contained in the Municipal Finance Management Act when allocating tenders.

The auditor general, in the 2020-21 report, identified 64 municipalities that are red-listed and at risk to continue as going concerns. These are dysfunctional municipalities. Of the 64, only one is in the Western Cape (3%), five of the 11 municipalities in Gauteng (46%) and five in Limpopo (19%). Most municipalities in North-West (41%), Northern Cape (35%), Eastern Cape (23%), Mpumalanga (35%), KwaZulu-Natal (13%) and Free State (43%) are under threat. Most of these municipalities are under the control of the ANC – the ruling party. The perception is that there are no consequences for transgressors.

We need urgent intervention to improve the financial sustainability of municipalities and are of the view that the proposals listed below will go a long way in solving the enduring challenges in local government.

- Structural changes are needed in local government and the various spheres of government need to be relooked at. Do we, for example, need provincial governments if the national government has its focus on the newly proposed district development model? This new plan also seems to be a non-starter because the least capacity and funding exist at the district municipal level. Between 40% and 50% of municipalities are under financial stress and require substantial financial and management support.

- We require capable, ethical, accountable and citizen-focused leadership in all municipalities, committed to serving the local people as public servants. In 2020, 1 544 public officials were still illegally doing business with the government.

- Urgent improved financial management is needed with a focus on revenue increase, including revenue collection strategies. The financial allocation to local government, known as the equitable share, needs to be increased drastically but there also needs to be more efficient use and spending of funding.

- Financial losses and fruitless and wasteful spending must be prevented at all costs.

- Improved procurement and supply-chain management must be enforced.

- Improved asset management systems and allocation of funding for repairs and maintenance of infrastructure must be ensured to prevent the total collapse of local infrastructure. A strict water and electricity loss-prevention plan must be implemented with consequences for transgressors.

- All irregular expenditure and processes should be monitored and unethical and fraudulent staff should be removed. There must be consequences for transgressors.

- The use of consultants should be minimised and financial department staff should be capable and, if not, trained, to handle all the financial management and control needed as a minimum requirement.

- Government, at all levels, including local government, should only appoint the “best of the best” and have a lean staff component. Only well-trained, committed and ethical people should be allowed to work in the government sector.

Professor Daniel Meyer is an economic development specialist and policy analyst at the School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.