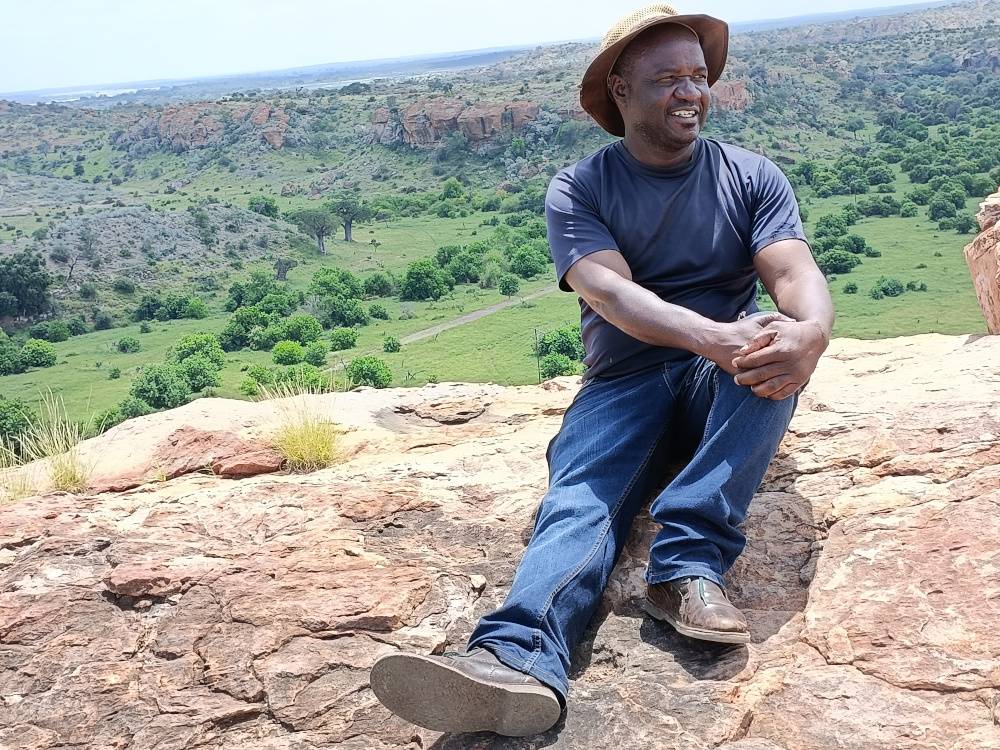

Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture Zizi Kodwa at one of the many cultural events that took place during National Heritage Month.

Looking back at a vibrant Heritage Month

As September draws to a close and Heritage Month nears its end, this is a time to reflect on the diversity and rich tapestry of cultures, traditions and heritage that make up the rainbow nation. The spotlight is on South Africa’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, which incorporates those from Africa, Asia and Europe. According to the Department of Sports, Arts and Culture, the 2023 theme of “Celebrating our cultural diversity in a democratic South Africa” offered an opportunity to honour those who came before us, reflect on how far we have come and pave the way for the generations to follow.

September aimed to showcase unity in diversity, an apt theme in a nation that has endured centuries of division under colonialism and apartheid. “Our rich and diverse cultures should unite us as a nation to promote and preserve our unique heritage by safeguarding it as a valuable resource for current and future generations,” explained Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture Zizi Kodwa. The aim this year, he added, was to depart from formal events and rather promote interactive celebrations.

In doing so, South Africans would be reminded to appreciate the unique things that set them apart, as well as the shared opportunities that bring them together. This, according to the department, is crucial to instil and enhance values of social cohesion and nation-building, especially among the youth.

Showcasing South Africa’s heritage and ‘Living Treasures’

The launch event, held in Limpopo in early September, featured captivating performances that showcased diverse indigenous music, dance and poetry. This also set the scene for the launch of a series of books featuring five “Living Human Treasures” — a gift from esteemed individuals who have dedicated themselves to preserving and passing on cultural knowledge to younger generations.

This included the late Koos Meiki Masuku, an indigenous conservationist who promoted medicinal knowledge; poet and novelist Themba Magaisa who writes in Xitsonga; dance teacher Tshimangadzo Sinyegwe who imparts cultural knowledge; Khoi and San leader Petrus Vaalbooi who shares history; and musician Thomas Chauke who does the same through song.

Throughout Heritage Month vibrant carnivals were held in districts across the country, where people dressed up in traditional outfits, listened to indigenous music, tasted traditional foods, and immersed themselves in their diverse cultures.

Throughout Heritage Month vibrant carnivals were held in districts across the country, where people dressed up in traditional outfits, listened to indigenous music, tasted traditional foods, and immersed themselves in their diverse cultures.

Throughout the month vibrant carnivals were held in districts across the country, where people dressed up in traditional outfits, listened to indigenous music, tasted traditional foods, and immersed themselves in their diverse cultures. This allowed all South Africans to actively participate in Heritage Month in their own communities.

The celebrations culminated in a vibrant Heritage Day festival in KwaZulu-Natal on 24 September, led by Deputy President Paul Mashatile. The many stalls featured traditional arts, crafts, attire, instruments and an array of indigenous foods. Stages came alive with local music and dance from across cultures — African, Indian, Afrikaner and more.

The event also marked the official opening of the 17th edition of the National Indigenous Games Festival (IGF), a week-long sporting event to honour the impact of sport on national identity and heritage. IGF is a school-focused sports programme that encourages young people to be active and participate in the games — instilling the significance of indigenous games at a school level, with the aim of one day making the games mainstream throughout the country.

Crucial to this is sports development and advocating for an active nation as aligned to the departmental mandate under various flagship programmes like #IChoose2Bactive – How about you?

Looking to the past for a better tomorrow

For South Africans, Heritage Month recognises how far the country has come on its healing journey. Divisions spawned by centuries of colonialism and decades of apartheid rule instituted a hierarchy of race, dispossessed black South Africans of land, suppressed indigenous culture and engineered tribal differences to divide and conquer.

The advent of democracy in 1994 brought about efforts to rediscover and unite our diverse heritage. This included repealing race-based laws, developing policies like the National Heritage Council Act to protect heritage, and embracing previously suppressed cultural traditions.

South Africa still grapples with challenges such as inequality, poverty and lack of social cohesion. Heritage Month aimed to spotlight the positive progress made towards uniting diverse cultures into a cohesive rainbow nation.

The vibrant music, dance, cuisine, crafts and more showcased during the month of September demonstrated the wealth of heritage that South Africans inherit. This can provide a foundation to continue building an inclusive and equitable society.

As the Department of Sports, Art and Culture, we reflect back on Heritage Month 2023 and acknowledge how it provided an opportunity to celebrate how far South Africa has come in recognising diversity as a strength. By valuing the varied threads that make up its cultural fabric, the rainbow nation can continue weaving itself into an ever more coherent tapestry.

The last words came from Minister Kodwa: “Unless and until we as Africans start documenting our stories and ways of life, we will continue to lament the disappearance of our indigenous knowledge systems. Let us therefore continue to celebrate our rich and unique cultures.”

Indigenous Games Festival unites South Africa through shared traditions

Indigenous Games Festival is an opportunity to celebrate Heritage Month by spotlighting nine traditional sports that have been passed down through generations, providing a thrilling showcase of indigenous games coming alive through friendly provincial competition. Teams from all nine provinces battled for bragging rights across the various codes. The line-up of traditional games on display included Dibeke, Drie stokkies, Iintonga, Jukskei, Diketo, Kgati, Ncuva, Kho-kho and Morabaraba.

Dibeke is a running and kicking game similar to football, but with an exciting aerial element. Teams score by kicking the ball over a centre line and completing runs between the attacking boxes.

Driestokkies tests balance and explosive power as players sprint and hurdle over sticks. Iintonga is a combat game in which opponents duel with sticks, aiming to strike their rival while defending themselves with a shielding stick.

Jukskei has similarities to the game horseshoes, with competitors pitching sticks at a target peg in a sandpit.

Morabaraba is a strategy game using cows on a wooden board, much like checkers.

Diketo and Ncuva rely on hand-eye coordination to scoop or place stones in patterned holes, while Kgati is all about rhythm and fitness, with players choreographing skipping routines. Finally, kho kho involves fast-paced tagging and chasing to “catch by pursuit”.

Not only are these games steeped in history, but they also build values including teamwork, discipline and sportsmanship. The games provide an active way for South Africans to connect with their heritage, representing indigenous knowledge passed between generations, often associated with ceremonies and milestones.

The festival promotes inclusivity, with teams composed equally of men and women. This allows female athletes the opportunity to compete and challenge stereotypes, providing a platform for greater representation at a high-performance level. While the games themselves take centre stage, the carnival atmosphere is also a huge drawcard, as the provincial teams march with pride and supporters come out in force to soak up the festivities. The colourful uniforms, official ceremonies, drums and dance create an electric mood.

The competitions cater to all skill levels, from grassroots entrants to seasoned provincial stars with junior, senior and masters divisions across the codes. This accessible approach helps drive mass participation by creating local heroes and inspiring more South Africans to embrace active lifestyles through indigenous games.

For organisers and participants, the Indigenous Games Festival is about more than medals and trophies. It’s about keeping traditions alive in a modern world and using sport to unite a diverse nation. The crowds boast grandparents who played these games in their villages, parents sharing the experience with their kids and the youth discovering cultural connections for the first time.

South Africa faces challenges of inequality, high unemployment and lack of opportunities for young people and these games provide a positive alternative to the vices that can entrap the idle. The teamwork, discipline and ethic of striving instilled through sports can positively influence lives. With the exciting atmosphere, cultural attractions and provincial pride on display, the Indigenous Games Festival has firmly established itself as a premier event.

As a nation, South Africa continues to search for shared experiences that unite across divisions of language, ethnicity and class. Sport has a profound ability to bring people together through a common passion. By celebrating games and traditions passed down by our ancestors, the Indigenous Games Festival taps into a unifying spirit that resonates across the rainbow nation.

Fierce competition at the National Indigenous Games Festival

The competition was fierce as citizens celebrated the country’s unique cultural heritage through traditional sports. The aim was to revive history, heritage and culture, as well as promote social cohesion and nation-building. The programme also gave over 950 athletes from eight provinces the opportunity to compete for various honours.

#HeritageMonth2023

#CulturalDiversityZA

#IndigenousGamesFestival

#IGF2023

#IChoose2BActive – HOW ABOUT YOU!

www.dsac.gov.za | Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok @SportArtsCulturRSA and Twitter @SportArtsCulture

Celebrating unity in diversity during Heritage Month

Every September, the country pauses to acknowledge the rich cultural heritage of South Africa — and that of each person who calls this country home. As Heritage Month draws to an end, the Mail & Guardian spoke to South Africans from all walks of life to find out what heritage means to them.

Henry Day

My heritage is pretty mixed! While my mom was born here, her parents came to South Africa in the 60s so she is French. I don’t identify with that culture as I don’t speak the language and struggle to understand the lifestyle. My dad was 100% South African. One of his ancestors came over from England around the time of the Anglo-Boer War and never left. I don’t see myself as English, Afrikaans or French — I’m South African! I celebrate with French cheeses and dishes paired with local wines. I also celebrate the small stories of good that come out of SA. I identify as South African, and that includes all the good and all the bad of this place we call home.

Nombulelo Mzobe – age 15

Heritage Day is a public holiday in South Africa that celebrates the roots and history of our diverse culture. The day was initially known as “Shaka Day” to commemorate the legendary King Shaka Zulu on the day he is presumed to have died in 1828. Today, Heritage Day recognises and celebrates the cultural wealth of our nation but I feel like Heritage Day should not be only about celebrating different cultures that make up the population of South Africa, it should be more like becoming together as one and being proud of who we are. Heritage Day should be about celebrating our background and the diversity of our country. The different kinds of clothes we wear when celebrating Heritage Day and the exquisite colours that make up those attires — this is therapeutic and influences me to be a walking proud black woman. Our heritage is so beautiful that I wish we could celebrate it every day.

Vivien Katzav

“My heritage is multicultural and multi-faceted and goes deeper than just superficial concepts like what I look like — which is Asian-German. It includes religious exposures of Buddhism, Catholicism, Judaism, and the awakening of consciousness and soul identity. My identity has been shaped by experiences of poverty and not fitting in under the Apartheid regime, with all the rejections, marginalisation and bias; in hindsight a gift that taught me the lessons of tolerance, resilience, acceptance and learning to love who I am. We celebrate Xmas and Chanukah, Easter and Pesach and of course births, birthdays and deaths — always with food! We blend our celebrations together to enjoy feasts together. You will never go hungry in my house! On birthdays we always make mein or noodles. This Chinese tradition bestows long life on the individual, so we make sure to keep our noodles long!”

Kgabisi Motene – age 16

“I am Tswana and we are known for our music, dance, clothing and passion for education. We originate from Botswana and my heritage is something I inherited. It is something you are born with, depending on your tribe and your family culture, on where you are from and how you identify. Heritage to me is something that sets each of us apart from the rest of the world and embraces who and what we are, and shows other people the beauty of our culture. As a young person I see my heritage influencing me to show me I belong and this helps me to understand myself and other different cultures, and helps me to understand identity.

Jayson Naidoo

“I define my heritage as an African Indian, but I am African first, born of South African soil. My heritage goes far back to the 1860s, when many Indians came to South Africa as indentured labourers through British colonialism. My heritage is celebrated through a South African feast of a traditional braai with a twist of Indian spices on the meats we braai. We usually have family over and celebrate our beautiful rainbow nation. My heritage influences my identity as African first by embracing the spirit of Ubuntu. I am because we are! I celebrate our diversity, inclusion and equity by being tolerant, inclusive and welcoming people with my values of love, integrity, generosity, humility and thankfulness. I live this through servant leadership and random acts of kindness and care.”

Akwande Moyo – 14 years old

My heritage, the Zulu culture, is a tradition that has been upheld and passed down from many generations ago. We Zulu people celebrate this tradition by spending some momentum moments together, singing and dancing to our traditional songs, eating delicious feasts and most importantly, wearing our traditional Zulu clothing. To me, heritage is like a pathway that we always need in our daily lives to distance ourselves from all our daily problems and stress. We can just focus on embracing our beautiful culture, spending more time together and reflecting more on our customs that have and always will be in our hearts.

Elna Schütz

Culturally I am a German South African and I feel like I’m celebrating my heritage whenever I’m in my community. When I am doing cultural activities like the German Christmas Market or singing songs in our language or eating certain foods … that plays a big part in how I see my heritage. But I also relate to things that feel South African — a good old braai where you look around and everybody looks different and seems different on paper and yet all are connected. I think of how diverse our country is and how all of that in some way, whether it’s similar to me or different, influences the world I live in. Being from a relatively small cultural group in South Africa makes me understand that everybody is a little bit different while making me so appreciative of all people.

Leilah Moodley – 15 years old

I am proudly a South Indian-South African. Rich aromatic spices, arms and necks adorned with heavy gold jewellery and palms tattooed with the most intricate henna patterns … these are just a few of the wonderful things associated with my culture. My family is Tamil but has been in South Africa for longer than I can trace back. My grandparents are still fluent in Tamil, and while I am not as linguistically gifted, I still love listening to Tamil music and songs. Music helps me feel connected to my family and my heritage. This, along with dressing up and cooking traditional foods such as idly and dosa are just a few ways I like to acknowledge my heritage. Being South African has allowed me to embrace my culture as well as the myriad of other cultures around me and to be proud of it all. That is the true spirit of the Rainbow Nation.

Exploring South Africa’s complex cultural archive

A crucial part of understanding South Africa’s rich cultural heritage involves examining archives and artefacts that provide glimpses into our past. As South Africa celebrates Heritage Month this September, however, we must approach these historical materials with a critical lens, considering whose narratives have been captured and whose voices may be missing or suppressed.

Amogelang Maledu is an interdisciplinary art practitioner working as an independent curator and researcher. “It’s crucial to be sceptical of official historical documents like archives, particularly in a country like South Africa, where a particular kind of knowledge was historically created on behalf of black people,” she cautions. “Historical narratives have been manipulated to serve certain interests, and archives are where these narratives reside, but they often contain inconsistencies, gaps, and questionable knowledge.”

Amogelang Maledu in front of a body of artworks by Thembakazi Matroshe, Ranji Mangcu and Yonela Makoba collected by UCT WoAC committee at the Michaelis Galleries in 2020. Maledu brings a critical, contemporary perspective in her archival work. (Photo: Lerato Maduna)

Amogelang Maledu in front of a body of artworks by Thembakazi Matroshe, Ranji Mangcu and Yonela Makoba collected by UCT WoAC committee at the Michaelis Galleries in 2020. Maledu brings a critical, contemporary perspective in her archival work. (Photo: Lerato Maduna)

Maledu’s work provides an invaluable perspective on working with archives, especially those related to black popular culture in South Africa. Her academic background in anthropology, visual culture studies and curatorship are critical to her curatorial lens, bringing a critical, contemporary outlook to her archival work.

Essential conversations for contemporary researchers

She says it is important to retain a sense of caution when dealing with institutional archives that carry remnants of colonial approaches to knowledge production.

In her role as a curator, she focuses on questioning the credibility of research conducted by outsiders. One collection Maledu has worked with is the Percival Kirby Instruments Archive at the University of Cape Town’s music department. She focused on one specific instrument from the collection, which contains over 600 musical instruments used in Southern Africa, most collected by Scottish ethnomusicologist Percival Kirby in the 1940s.

Maledu notes that one must be critical of Kirby’s position as an outsider collecting and cataloguing instruments of African origin and the context in which he acquired these instruments: “This raises questions of ethics. How did he acquire these instruments and gain access to such a vast material heritage? These are important questions.”

She says this also highlighted issues related to the gaze of ethnomusicology and anthropology, which often involves othering and fetishising certain material cultures. “My responsibility is to raise questions about the credibility of such research while highlighting the continued relevance of these musical instruments in contemporary life,” she explains.

In examining the Percival Kirby Instruments Archive, one particular drum caught Maledu’s attention — an instrument dubbed “Isighubu” in Zulu, purportedly used during the Bambaataa Rebellion against British rule in 1906.

Beyond its specific historical significance, the drum’s name evokes broader ideas of spirituality, healing and transcendence in African cosmologies. “This drum fascinated me; it’s a register of history that continues to resonate in contemporary music-making,” she explains. “It remains relevant in various musical practices today, and I explore these discussions and consider isighubu in relation to popular music, specifically a musical genre in South Africa referred to as Gqom.”

The drumbeat of history echoes to this day

This genre, she explains, primarily consists of electronic music produced on computers without traditional instruments. Instead, electronic software recreates drums to produce percussive, heavy music. This music is created by black youth, many of whom come from townships and backgrounds marked by scepticism toward the country’s post-apartheid progress. ”These young artists find autonomy and agency. They create paths to success through their creative practice of electronic music production, leading to upward social mobility,” she says.

The connection between the 1906 drum and modern Gqom music highlights the continuity of music as an expression of resistance across generations of black South Africans facing oppression: ”Music, born out of necessity, becomes a source of defiance, echoing the historical significance of the drumbeat in our country’s history. Music, as a timeless and self-referential art form, plays a significant role in this process, connecting different generations through practices like interpolation and remixing. This remains a significant marker of defiance throughout generations, revealing commonalities and shared impulses in our history, and allows us to trace threads of history, making archival work an ongoing process.”

Silencing the past

Beyond interpreting archives, Maledu says it is also important to engage with the absence of sound in many museum collections of African instruments. While preservation is key, the collection of these instruments effectively silences them through restrictive exhibition practices that echo colonial mindsets: “Working within the Kirby collection, I noticed how these instruments were locked away in cabinets of curiosity. They were presented as objects to be gawked at rather than heard. As a curator interested in instruments’ sound and musicality, this kind of display was insufficient to the modality of their utility — music and sound.”

She says these instruments were silenced by the colonial gaze, “It didn’t make sense to me that these objects with the inherent utility of making music were captured and silenced by colonial processes; even in the contemporary moment, they remained silent within the music collections at the University of Cape Town.

To address this, she removed the isigubu from its cabinet and contextualised it within its historical frameworks. “Curators have a responsibility to surface questions and explore the relevance of artefacts like isighubu within the context of today,” she explains.

She encourages reinterpreting archives in ways that uncover meanings and narratives relevant to the current sociocultural moment while remaining aware of the gaps and missing voices in many official archives that reflect broader processes of exclusion and marginalisation. “Despite their limitations, there is utility and value in the Archive; sometimes, we need to reevaluate the archive in ways that are relevant to the present moment.”

As a curator, Maledu aims to bridge past and present, finding relevance between historical artefacts like isighubu and contemporary cultural practices. The past, she says, is ever-present: “My approach to archives isn’t limited to the present; I view them through a continuum of past, present, and future, emphasising the circularity of history and life.”

Bridging the gap between then and now

By giving a new voice to archival materials, Maledu’s work provides a model for critically engaging with South Africa’s complex heritage. As South Africa confronts the biases of the past and subsequent omissions in and of many official narratives, emerging perspectives from researchers like Maledu allow for reflection and reframing through a contemporary, socially-conscious lens.

The nation’s diverse cultural heritage belongs to all South Africans, and it is the duty of archivists, curators and artists to ensure these stories are told in ways that empower rather than silence. — Jamaine Krige

Reviving ancestral wisdom and traditional food systems

On the outskirts of a town in South Africa, a grandmother carefully tends her crop of millet, using organic farming methods passed down through generations. She speaks knowledgeably about the land and seasons, informed by decades spent honing the practices passed down to her from her grandmother. She is not alone. Across southern Africa, a movement is growing to reclaim such ancestral wisdom and promote indigenous food systems as a solution to modern crises.

Food and agriculture are deeply intertwined with the cultural heritage and identity of communities across South Africa. Experts emphasise that preserving and promoting traditional farming methods and cuisine is key to empowering rural farmers, promoting food sovereignty and building resilience against modern challenges such as climate change, inequality, food insecurity and environmental degradation.

Director of EarthLore Foundation Method Gundidza says there is an undeniable link between traditional knowledge, ecosystems, food and culture.

John Nzira, founder and programme manager of Ukuvuna, explains that concepts like permaculture and agroecology have ancient roots in Africa. “You cannot separate us from our culture, food or environment, and permaculture is about creating healthy systems where life can thrive.”

Reviving and celebrating traditional practices as part of South Africa’s living heritage is an opportunity to remember the interconnectivity of social, ecological and cultural dimensions that shaped indigenous food systems. “Healthy ecosystems produce healthy plants, and healthy plants sustain healthy individuals and societies,” he explains.

Preserving communal values

Dr Brittany Kesselman is a food systems researcher and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Cape Town. She says it is important to remember that food systems — historically and today — encompass more than just farming practices; they entail all activities and every person involved in not only the production but also the processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food.

Digging deeper into South Africa’s food heritage reveals a complex interplay between cultural values, environments and historical forces that have shaped the country’s food systems over time.

Pre-colonial food systems in South Africa upheld values like hospitality, reciprocity and a close connection with nature. Practices like ilima and letsema — collective community farming initiatives — stem from and reinforce mutual reliance and interdependence. “These practices integrate animal and crop systems, extensive knowledge of wild plants and natural cycles, festivals and celebrations that ensure the sharing of resources,” Kesselman explains.

This critical connection with nature is ingrained in various aspects of the region’s indigenous food systems. “Traditional agricultural calendars linked the times for sowing and harvesting to natural phenomena like the flowering of certain trees, the arrival of certain bird species or the position of certain constellations,” she says. “This showed a very close connection to natural cycles, which are reflected in the names of the months in many indigenous South African languages.”

John Nzira, founder and programme manager of Ukuvuna.

John Nzira, founder and programme manager of Ukuvuna.

Traditional practices reflect close observation of local ecological contexts — in contrast with industrial farming’s attempt to override natural limitations, dominate the natural world and prioritise profit over people. Unequal land distribution and exploitative labour conditions became entrenched as agriculture served colonial markets.

“Traditional food systems were developed over an extensive period of time, in particular places, responding to specific needs. There is great wisdom in these systems, and we need that wisdom to face today’s challenges,” she says.

Remembering our roots

Director of EarthLore Foundation Method Gundidza agrees. “We have entered into a period where we have really forgotten how to live in harmony with nature, how to farm in a responsible way, how to harvest and eat responsibly and how to protect the environment,” he says.

Gundidza says there is an undeniable link between traditional knowledge, ecosystems, food and culture. “Nothing was done just for the sake of it,” he explains. “Everything, even spirituality and spiritual practices, was embedded in the ecological understanding of local ecosystems.”

Offering the first fruits to the land shows gratitude for nature’s bounty, and helps sustain the forests and the creatures that reside there. “It is to understand and honour the role of the forest, of the river, of the mountains and animals and insects in the production of food,” he says. “Because the insects do not live on our farms, but we cannot farm without them. And for me, these are the critical issues that have been forgotten.”

The Johannesburg-based organisation works with communities in South Africa and Zimbabwe to revive ancestral wisdom, traditional seeds, indigenous farming methods and land-honouring rituals. In doing so, food security can be enhanced, climate change navigated and the balance between the cultivated and the natural that has for too long been ignored can be restored.

Preserving traditional practices against the odds

Colonialism and apartheid subjected traditional foodways to immense disruption and repression. Kesselman says it’s “amazing that any traditional methods still exist today, given the level of disruption and repression that colonialism and apartheid entailed”.

She explains that until recently, there have been attempts to impose “green revolution” style industrial farming involving chemicals, hybrid seeds and machinery, often to the detriment of both local communities and environments. “Smallholders are often on marginal lands without access to water, while large-scale commercial farmers continue to have the best land — or what was the best land before years of extractive production.”

Nzira says many smallholder farmers continue to employ ancestral methods that reflect close cooperation with nature — despite relentless pressure to “modernise” and adopt Western industrial farming techniques. Practices like seed saving, using natural fertilisers and medicines, and protecting sacred species like baobab trees are not uncommon in rural South Africa.

Agrobiodiversity — cultivated through strategies like intercropping, crop rotation and manure to promote soil health — also boosts resilience. Leaving fields fallow periodically conserves fertility. “This is traditional knowledge that dates back millennia; it has been dormant but it is still there,” notes Gundidza.

Resilient seeds for resilient communities

He says locally adapted seeds do not require yearly purchases, thus increasing self-reliance and food security: “We put production back in the hands of the people, and this promotes self-sufficiency and economic empowerment.”

Seeds like millet, sorghum, amaranth and cowpeas are nutritious staples that uphold food security. Nzira adds that small-scale farmers traditionally cultivated a wide variety of hardy, resilient crops that were nutritious and well-suited to local conditions. “Our indigenous crops are climate resilient and very nutritious,” he adds.

Gundidza agrees that the diversity of traditional seed varieties builds community resilience to climate shocks. Some seeds are drought-resistant, others are more resistant to heavy rainfalls; some thrive in hot weather while others survive frost. Having these varieties helps farmers harvest successfully despite erratic weather patterns.

As younger generations move to cities for jobs, traditional knowledge is not passed down, despite the fact that these practices hold wisdom for addressing modern sustainability challenges and strengthening community resilience.

For Gundidza, ancestral wisdom should be the foundation upon which new solutions are built. “If we abandon it, we lose that solid grounding,” he warns. “Modern knowledge should build on what our ancestors knew, because the way our grandmothers did things worked, even if they did not know why.”

The path to a sustainable future

As movements like food sovereignty gain ground, traditional knowledge offers solutions to empower farmers, nourish communities and conserve nature for future generations, showcasing how equitable and sustainable food systems work.

Policies are needed to support smallholder farmers with inputs like open-pollinated seed versus GMOs or chemicals. Agricultural education and training is vital, as is documenting indigenous knowledge. Building home gardens and community gardens grows a culture of healthy, local eating.

To secure the future of traditional agriculture, land reform is needed and the government must invest in programmes that recognise and promote agroecology as a viable, sustainable option.

Kesselman says enhancing local production and distribution should be prioritised over export monocultures: “Government should support people to produce healthy foods for their communities to be distributed via alternative, localised markets. This is how traditional food systems worked.”

Revitalising the ancestral wisdom embedded in indigenous foodways is an opportunity to remember our profound connection to the land and nourishing a more just and sustainable future. Kesselman says this is the only way “to ensure our food systems can feed us in the face of the climate crisis, and stop contributing to inequality, poor health outcomes and environmental destruction”.

Gundidza stresses that returning to Africa’s roots holds promise for the future: “Being traditional isn’t backward — it’s the sustainable way forward. We build resilience by honouring ancestral wisdom.”