President Cyril Ramaphosa. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

President Cyril Ramaphosa has argued in papers filed to the constitutional court that the section 89 panel that recommended he face an impeachment inquiry strayed beyond its mandate.

“It was also unfair to me because it raised matters to which I was never invited to respond,” he said in his application asking the court to set aside the report that has plunged the ruling party into existential crisis.

Ramaphosa said in his submission to the panel, headed by former constitutional court justice Sandile Ngcobo, he confined himself to speaking to the four charges set out in an impeachment motion tabled by the African Transformation Movement.

He stressed that he had had six working days to respond to the letter from the panel, sent on 28 October, which asked him to reply to the “all relevant allegations against me”, and read this to mean those set out in the motion.

“I understood the panel’s invitation to mean that I was invited to respond only to the allegations relevant to the four charges against me.”

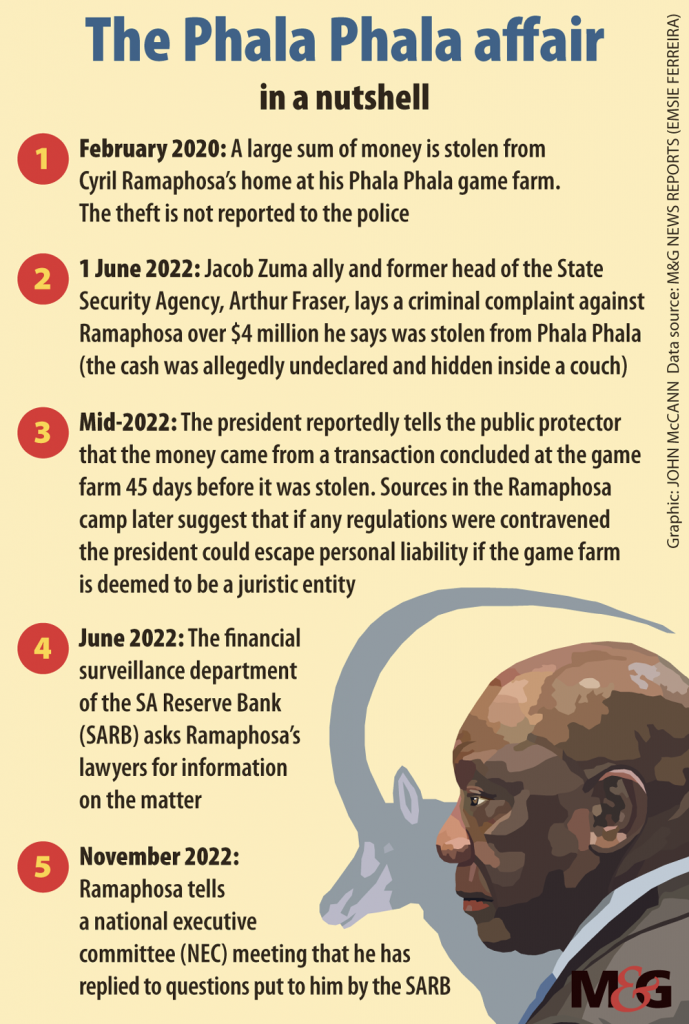

It was expected in legal circles that Ramaphosa may raise this argument in defence to the report’s assertion that his version of events surrounding the burglary at his Phala Phala game farm in 2020 was “vague and leaves unsettling gaps”.

The panel found that the president may have a case to answer on charges that he breached the law and the Constitution, particularly with regard to the source of the money stolen from his farm, the actual amount that was taken and the efforts that ensued to recover it.

It further concluded that there was prima facie evidence that the president breached anti-corruption legislation by failing to ensure that the theft of more than half a million US dollars was duly reported to the police.

But in his papers, the president argued that the rules governing the process for removing the president in terms of section 89 of the Constitution defines the panel’s mandate as making a value judgment as to whether “sufficient evidence” exists to show that he committed a serious crime or violation of the Constitution or was guilty of serious misconduct.

“It seems clear that it misunderstood its mandate in at least two aspects.”

First, it seemingly conflated the meaning of “prima facie evidence” and “sufficient evidence”, where the latter is the more stringent and correct test.

“It interpreted its remit to ‘determine whether sufficient evidence exists’ to mean ‘whether there is a prima facie case against the president,” he argued. “The panel was thus mistaken.”

The panel further failed to understand that a potential finding of serious misconduct or a serious breach of the Constitution or the law, as defined by the rules of the National Assembly, is confined to instances where the president acted deliberately and in bad faith.

That it did not follow its brief was evident in a passage in the report where it ventured that its task was to conduct a preliminary assessment of the charges advanced in the motion to determine whether he had a case to answer, the president argued.

This meant it failed to restrict itself to consider whether these, if proven, would be grounds for impeachment and was supported by sufficient evidence.

“I am advised and I submit that the panel set itself on the wrong path. It could not conduct a rational inquiry nor could it reach a rational conclusion.”

The panel located grounds for a case to answer not only in the narrative former intelligence boss Arthur Fraser told the police when he brought charges against Ramaphosa in relation to the burglary, but in what it termed the evident holes in the president’s version of what happened at his farm.

Ramaphosa said his submissions seemed to have diverted the panel from the inquiry it was meant to conduct, as per the rules.

Its work should have not have started with the presumption that the charges stood, and then moved to consider whether his version was strong enough to defeat those charges.

Instead, it should only have considered his version if the charges were substantiated.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)Here, he continued, it erred from the outset by not following the default rule in excluding hearsay evidence, despite writing that he was correct in criticising “Fraser’s statements as full of hearsay”.

“Save for the limited evidence I introduced in my response, there was no evidence before the panel.”

Ramaphosa said the panel committed the further fatal error of not considering whether information put before it by Fraser was credible or lawfully obtained, including a confidential Namibian police report.

“It is likely that the Namibian report, if it is at all legitimate, landed in Mr Fraser’s hands unlawfully.”

The same applied to audio clips said to be of suspects being interrogated. The panel failed to question the credibility of the material. and could not escape an obligation to do so by saying its mandate did not allow it to conduct an investigation or test the veracity of information.

“In situations like this there is every incentive to hoodwink decision-makers to make rushed decisions based on half truths,” the president argued.

“This is what appears to have happened.”

The report is set to be debated in the National Assembly on Tuesday. Only a simple majority is needed for it to be adopted, in which case the legislature must then establish a committee of members from all parties to conduct an impeachment inquiry.

There were calls from allies of the president on Monday for the debate to be postponed given that the matter is now before court.

Ramaphosa, who was last week pulled back from the brink of resigning by his allies, is reliably understood to be loath to subject himself to the long and distracting process of an impeachment inquiry.

Asking the apex court to overturn the report is not only a legal strategy but also a political one and in that sense it has worked so far.

In the public space, the president has shifted the focus away from the panel’s doubts about the credibility of his account about what happened at Phala Phala to the credibility and integrity of its findings.

And in the ANC’s crisis meetings on the subject, it has allowed the Ramaphosa camp to argue that it would be rash to recall him on the basis of a report that could be struck down.

The rules governing the section 89 process for removing a president were written in response to a 2017 constitutional court ruling — Economic Freedom Fighters and Others vs Speaker of the National Assembly and Another.

The applicants were opposition parties who charged that parliament failed to put processes in place to hold then president Jacob Zuma to account for breaching the Constitution by failing to heed the public protector’s findings on the Nkandla scandal.

In a majority judgment, the court held that the Constitution requires a specific procedure, and therefore a specific set of rules, for impeachment.

Specifically, the majority judgment said, parliament must participate in a process to determine whether the constitutional conditions for removing a president had been satisfied before calling an impeachment debate and vote.

The Phala Phala scandal marks the first time that these rules are being applied, and the panel marks the first step in that process.

The case, often simply referred to as EFF2, ironically became better known for a debate about whether the court should intervene in a dispute involving the processes followed by the legislature to address the misconduct of the executive, than for its conclusion.

Chief justice Mogoeng Mogoeng objected, in a dissenting judgment, that his colleagues erred in prescribing to the legislature and that this risked rendering an eventual impeachment process rigid.

In a scalding criticism he demanded be read out in court, Mogoeng called it “a textbook case of judicial overreach – a constitutionally impermissible intrusion by the judiciary into the exclusive domain of parliament”.

Read the full report of the Section 89 independent panel below