Professor Eddy Maloka, Chief Executive, APRM Continental Secretariat, says our assumptions often alter only when there are cataclysmic changes in the world. (Photo: UCT News)

COVID-19 — Africa’s Response

I have been working on African issues in different capacities for some 30 years — as an academic, in the policymaking space, and as foreign policy practitioner. But I didn’t see the phenomenon that is COVID-19 coming.

The reason for this is in our assumptions, or paradigms — that is, assumptions we make about the external world as something that exists independently of us.

We are part of this reality as a biological life form, and we can only experience the external reality via our senses.

Through these senses, we build what we consider to be a body of knowledge; in some cases, this body of knowledge poses as science.

We live in the realm of doubt and probability because, factually, we don’t really have a full picture of what is out there, the reality that exists outside of our senses.

These assumptions are reflected in the tools we have developed to assist our senses make better and proper sense of reality and the future, which also resides in the domain of the unknown.

These tools range from our microscopes and telescopes to formulae and theories we have to help our senses process and make sense of external reality.

For us who work for bodies such as the African Union, we have analytical and forecasting tools that we use to determine and generate data about the physical facts of our world.

We analyse this data and try to make projections about the future. The problem with assumptions is that, in as much as they empower our senses to enable us to engage with the external reality in a better way, they also create blind spots for us.

Assumptions are like a vehicle – a beautifully built vehicle. We sit inside it and drive on the highway. But this vehicle has blind spots.

Its structure and your sitting position may prevent you from seeing certain things; even things that could be of danger to you and your car.

We make up for this weakness in our cars by turning our necks to check the blind spots, but in life we don’t always turn our necks. We take our assumptions for granted and as being self-evident.

We miss so many things because of the many blind spots; we miss even those things that pose an existential danger to us.

Our assumptions are not fixed. Some are scientifically determined; others are the product of our socialisation and culture; and others are derived from our religious beliefs. These assumptions are also not fixed; they change with time.

In many cases, our assumptions alter because of cataclysmic changes in the world, or within countries, such as a world war, a famine or a flood.

The end of the Cold War at the beginning of the 1990s was one such cataclysmic change, one that led to not only the end of the former Soviet Union, but also led to the creation of new states in Eastern Europe. The independence of South Africa was also a product of this historical moment.

We are now at another turning point in history due to COVID-19, and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) will be affected, particularly its methodology and tools.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed the first recession in 25 years, with a devastating impact on lives and livelihoods.

Vaccines have not reached many African countries: the rollout systems are exposing weaknesses within governance and social systems, and testing our countries’ abilities.

The average African economy contracted by 2.5% in 2020, while massive job losses, businesses closing and lack of access to resources have further exposed underlying inequality. The number of people living in poverty in Africa is expected to rise by an alarming 29-million in 2021 alone, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

These challenges continue to prove to be beyond any government or stakeholder group’s scope to address on their own. Fortunately, a growing movement of open government champions across Africa — arising from governments and civil society — is showing an alternative, more hopeful path forward.

For years to come, historians will debate not only the impact of COVID-19, but also whether it was exacerbated by negligence on the part of decision-makers who had assumed, across the board, that humanity had triumphed over disease because of our advances in science. A disease doesn’t become pandemic on its own. This happens when humans, who are themselves vectors of the disease, fail to cope with it.

Our belief in our “triumph” over disease was not unfounded. Thanks to our microscopes, disease is no longer invisible to us; most are not invincible in the face of our vaccine technology and effective medical treatment.

In her article How pandemics shape social evolution, published in the October 2019 issue of the journal Nature, Laura Spinney refers to “a pervasive, dangerously complacent attitude in the late 1960s”, whereby “international public-health authorities were predicting that pathogenic organisms, including the parasite that causes malaria, would be eliminated by the end of the twentieth century”.

Christian McMillen observed in his “Pandemics: A Very Short Introduction” (2016): “The 1918 influenza pandemic was an event. Unlike malaria and tuberculosis — the perpetual pandemics — influenza comes and goes. In this way it is more like smallpox or plague. Of course those two diseases are no longer major global threats. Influenza is. When H5N1 appeared in humans in 1997, and the novel strain of H1N1 turned up in 2009, the world was reminded of the possibility of another 1918. It has not happened yet.”

Motivated by a duty to contribute to how Africa can respond to this pandemic, the APRM thought it would be worthwhile to establish how its member states are acting to combat the spread of the virus and to deal with its impact on their people and economies.

It has compiled a report that recounts efforts by various institutions and provides recommendations for countries to adopt, such as ensuring their COVID-19 containment measures protect human rights.

This report seeks to provide comprehensive information on COVID-19 and the various governance responses, measures and strategies that have been implemented by member states.

More importantly, the report seeks to facilitate evidence-based policy responses to the crisis and to enable information sharing.

It employs a scientifically sound, horizon-scanning consolidation of trends with a view to mapping out the multi-sectoral policy responses across the continent.

Its primary methodology was the collection of data through APRM national structures and to study the context and responses to the pandemic in all African states across all five regions.

The report notes that the outbreak of COVID-19 has compelled governments and multilateral agencies across the globe to reflect on the nature and effectiveness of public institutions.

It concludes with a set of recommendations for consideration by the African Union (AU), member states and the APRM. — Professor Eddy Maloka is the Chief Executive, APRM Continental Secretariat

APRM’s report represents collective effort to counter spread of COVID-19

Professor Fatima Zohra-Karadja, chairperson of the APRM Panel of Eminent Persons

Professor Fatima Zohra-Karadja, chairperson of the APRM Panel of Eminent PersonsHumanity is facing an unprecedented health crisis, one that has taken the lives of millions of people around the world and has repercussions for all socioeconomic sectors. This crisis has transformed our everyday habits and behaviour.

The cause of this health crisis is a virus called COVID-19, which originated in China and has spread across the world exponentially.

Even today, the coronavirus continues its ravages; specialists in epidemiology and public health only predict the end of the health crisis in several years’ time.

The nature of COVID-19 response measures and how states go about enforcing these measures have led to the emergence of a wide range of governance and human rights problems. The concern is that we face the danger of the COVID-19 pandemic descending into a human rights emergency.

It is not simply a health challenge. Even as a health challenge, for us it also essentially constitutes a pressing human rights issue. The morbidity and mortality that the virus causes represent a serious threat.

COVID-19 is also a human rights issue. It threatens the right to health and the right to life, the most fundamental of our rights. It is on this account that the African Commission issued the first statement of the AU human rights system, on 28 February 2020.

This has underscored the imperative and legal necessity within the framework of Article 1 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights to proactively take measures for protecting people from the threat that COVID-19 poses to their health and lives.

Each region and country in the world is organising to curb the spread of this virus and to mitigate its socioeconomic impacts by taking a series of measures.

In Africa, the specialised institutions and organs of the African Union as well as the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are co-ordinating with the governments of member states to overcome this pandemic and to relieve the populations of the negative effects.

In this regard, the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) is working hard in a co-ordinated manner with the African Union Commission and Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) to propose adequate solutions to member states, so a robust response to this pandemic can be formulated.

The APRM as a self-assessment instrument on governance in Africa must also do its introspection in light of this unprecedented situation to adapt and to improve its tools and methodological approaches in order to respond in advance, and to propose solutions to member states in terms of resilience to shocks and disasters of this type.

This preliminary report on the response of AU member states to COVID-19 is the contribution of the APRM to the collective effort to counter the spread of the virus and to mitigate its effects in Africa.

The report gives an overview of the health situation in AU member states, and particular in terms of lethality, morbidity and mortality due to the coronavirus, as well as the various measures and strategies put in place by AU member states to counter the effects of this pandemic.

After a scientifically conducted analysis, based on the reality of the facts reported by the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and the countries, the report presents recommendations on matters of governance that the member states should implement individually and/or collectively to achieve the following: curb the spread of the virus, mitigate its effects, and prepare a response in the event of a disaster such as this in the future.

The purpose of this preliminary report is to provide content that can be used to enrich the debate on the governance response to COVID-19 on the continent. The report is not the final statement on the question of an effective governance response to the pandemic. It seeks to support the articulation of evidence-based governance responses in member states and to facilitate sharing of tested approaches on the governance response to COVID-19.

Additionally, the report provides a basis for the assertion that an effective governance response would enhance the effectiveness of efforts in the public health, biomedical, economic and social spheres.

This report will also be included in all the knowledge products developed by the AU organs and governments of member states on this subject in order to guide decision-making for the response and to guide reforms in governance in Africa.

The report is addressed primarily to AU organs, the regional economic communities and the governments of the member states.

As regards the member states, the report recommends, among others, that governments should establish inclusive national institutional and legislative mechanisms for disaster management. Governments should also decentralise responsibilities and capacities for disaster management, while implementing containment measures within a framework that respects the rule of law and the human rights of citizens.

Secondly, the report is addressed to the general public, particularly to academia/researchers and all those who are interested in governance in general.

As pertinent governance questions arise regarding the balance between human freedoms and public health and safety concerns in relation to COVID-19, the world, including Europe and North America, continue to suffer steady economic and social declines as a direct result of their lockdown policies, which constrain movement in the populations, and constrict the movement of goods and provision of the full spectrum of services. The implications for economic, civil, political and social freedoms are clear. These freedoms have now been rolled back and limited as countries pursue the public health and safety goals needed to curb the pandemic.

The civil liberties of African citizens are at risk during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, which may have serious repercussions for human rights. (Photo: Luca Sola/AFP)

The civil liberties of African citizens are at risk during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, which may have serious repercussions for human rights. (Photo: Luca Sola/AFP)

A challenge for governance during the epidemic is determining the form and duration that this policy may be applied without a significant rollback in development gains, livelihood and/or infringement of fundamental human rights. To date no quantitative benchmarks have been established by multilateral institutions, in either public health epidemiological terms or national economic terms, to guide countries in the phased implementation of these measures.

The application of the policy remains experimental and the political ramifications for Africa may be serious if the proportion of the population in favour of lockdowns diminishes due to pressures the policy imposes on livelihoods.

My thanks also go to all my fellow members of the APRM Panel of Eminent Persons who, through their very relevant comments, have improved the quality of this report.

Finally, I would like to thank the members of the working group from selected APRM member countries for their support in drafting this report.

Finally, I would like to thank all those who contributed to the preparation of this report, starting with the Chief Executive of the APRM Secretariat, Professor Eddy Maloka, who has spared no effort to carefully supervise the technical production of this report, despite the difficult situation of lockdown imposed in South Africa.

I invite member states to take ownership of the recommendations contained in this report and implement them effectively. — Professor Fatima Zohra Karadja is Chairperson of the APRM Panel of Eminent Persons

APRM launches Africa’s governance response to COVID-19

On 8 June 2020, the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) held a virtual launch of its Preliminary Report on Africa’s Governance Response to COVID-19 attended by various stakeholders, including APRM’s chief executive, Eddy Maloka.

The virtual launch came shortly after several African Union member states went into strict lockdowns, introducing severe COVID-19 restrictions, travel bans and quarantine measures in a desperate bid to curb the spread of the pandemic and to minimise physical contact.

This preliminary report presents the outcomes of a study conducted to examine Africa’s governance response to the new coronavirus. It presents a summary of the immediate measures, and medium-term and long-term policy responses to COVID-19, which was designated a pandemic on 11 March 2020.

The aim of the study, which recounts efforts by the African Union led by President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa and the various agencies of the Union, was meant to place governance at the centre of the response to COVID-19 pandemic in the African continent.

According to the Africa Centres for Disease Control (Africa CDC), the scale and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa constituted a cause for great concern.

The preliminary report highlighted commendable policy responses that have been adopted during this period and presents recommendations for the AU and member states in the biomedical, public health, economic and governance spheres.

These included the ratification of the African Risk Capacity Treaty (ARC Treaty) as well as the assessment of the scientific, technological and institutional capacities of member states, including their capacities for vaccine research and development, to contribute to enhancing their ability to prepare for and manage disasters.

Recommendations for AU member states called for countries to ensure that their COVID-19 containment measures protected human rights, among others.

During his opening remarks, South African Public Service and Administration Minister Senzo Mchunu emphasised the wisdom of collective action and collaboration in order to defeat the pandemic.

Both Mchunu and Maloka said that the report was an indication of what could be achieved through working together as African states without negating national sovereignty, but rather banding together to solve a crisis that had engulfed the entire continent.

“The APRM is a mechanism envisaged to promote good governance and socioeconomic development through the adoption of policies, standards and good practices that will lead to political stability, economic growth and sustainable development on the African continent. The APRM uses a holistic review process that distinguishes the mechanism from other institutions through inclusive dialogue, independent and objective reviews, peer learning and compliance monitoring,” said Mchunu.

The Minister of International Co-operation, Dr Naledi Pandor, also attended the virtual meeting and applauded the AU’s ability to continue working during these trying times as well as the establishment of the African COVID-19 Response Fund, which has thus far received $26-million in pledges, and the Africa CDC, which had also raised $35-million in pledges.

“This is commendable considering that nine African countries have had their credit ratings downgraded to junk status since the breakout of the pandemic in Africa,” said Pandor.

She added that the pandemic had exposed the inequalities in healthcare and further brought to light research and innovation gaps.

During his opening remark, APRM Focal Point in Chad, Khayar Oumar Deffalah, cautioned that COVID-19 had almost eclipsed other pandemics that Africans are grappling with; as a result, they receive little or no media attention.

He urged that the final report should include strategies for malaria, Ebola and other diseases, as their effects were also devastating on the African continent, especially on children.

The first case of COVID-19 in Africa was reported in Egypt on 14 February 2020. By 16 May 2020, 54 countries in Africa had reported more than 81 613 cases and about 2 707 deaths from the new coronavirus.

Although African countries have resources to pay for the reagents, they are unable to purchase them because of restrictions on export of medical materials in most countries.

The epidemiology of the epidemic in Africa presented below, therefore, may offer a mere indication of the actual situation.

From a governance response perspective, such a challenge requires multilateral interventions in mediating and reshaping international cooperation in times of crises.

Co-operation across Africa is starting to happen, and Africa CDC had a plan to distribute one million test kits by mid-May 2020 across the continent. — Charles Molele

The data below is presented by regions of the African Union

(The data keeps changing as governments report new cases of COVID-19 infections, deaths and recoveries)

NORTH AFRICA

The first case of coronavirus in Africa was detected in Egypt in February 2020. The virus was thereafter detected and reported in Algeria and other countries. Egypt remains the country with the highest number of confirmed cases (11 719) and deaths (612), followed by Algeria with (6 821) confirmed cases and (542) deaths associated with the virus. More people are recovering from the virus in Morocco (3 487) than Algeria (3 409) and Egypt (2 950). The fatality rate in North Africa indicates huge differences across the states in the region. Mauritania has the highest fatality rate (10%) followed by Algeria (7.95%) and Egypt (5.22%) in the region, and later detected in the rest of Africa.

WEST AFRICA

The West Africa region is also confronted, in selected parts, with the triple human security threats in the form of conflict, migration and the pandemic.

Ghana has registered the highest cases of COVID-19 in the region, with 5 735 confirmed cases, 29 deaths and 1 754 recoveries, followed by Nigeria with 5 621 confirmed cases, 176 deaths and 1 472 recoveries.

The country with least cases is The Gambia, with 23 confirmed cases of COVID-19, one death and 12 recoveries. West Africa has registered the second highest number of infections, but the second lowest rate of fatality. Seven countries out of the 15 countries of the West Africa region have registered less than 2% fatality rate.

CENTRAL AFRICA

According to the 16 May 2020 data from the WHO and Africa CDC, the situation in Central Africa remains fluid as countries confirm cases as and when they occur. Cameroon has registered the highest cases of COVID-19 in the region, with 3 105 confirmed cases, 140 deaths and 1 567 recoveries.

The Central African Republic has 327 confirmed cases, no deaths and 13 recoveries. The Republic of Chad registered 474 cases, 50 deaths and 111 recoveries.

Congo-Brazzaville has since registered cases, 15 deaths and 87 recoveries. DR Congo has registered 1 455 cases, 61 deaths and 270 recoveries and Equatorial Guinea has a total of 594 cases, seven deaths and 22 recoveries. Gabon has 1 320 confirmed cases, 11 deaths and 224 recoveries.

And finally, Sao Tome and Principe has registered 235 cases with seven deaths and four recoveries.

While Central Africa has registered the second least number of cases on the continent, it has the second highest fatality rate. Within the region, Chad has the highest fatality rate (10.55%) followed by Cameroon (4.51%) and DRC (4.19%). The Central Africa Republic did not register any COVID-19 related deaths up to 16 May 2020.

EAST AFRICA

The East Africa region, despite its broad human security challenges, has registered the least cases of COVID-19 infections.

The region has the third highest fatality rates on the continent. Within the region, Kenya is the country which registered the highest fatality rates (6.02%), followed by Sudan, which registered 4.24%, and Tanzania with 4.13%.

This was followed by Somalia, with 1 357 confirmed cases, 55 deaths and 148 recoveries, and Djibouti with 1 331 confirmed cases, four deaths and 950 recoveries.

The countries with less cases are Seychelles and Burundi with 11 cases, no deaths and 10 recoveries; and 27 cases, one death and seven recoveries respectively.

SOUTHERN AFRICA

As of 16 May 2020, only Lesotho remains as the country in the region with just one reported case of COVID-19. In southern Africa, the highest number of COVID-19 confirmed cases has been reported in South Africa, which registered 90.31% of the total number of infection cases in the region.

The other countries of the region have less than 10% of the total confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the region. South Africa is the most globally connected country in the region, with ports that have relatively much higher traffic with the rest of the world in comparison to its neighbours.

Within the region, Zimbabwe is the country with the highest fatality rate (9.09%), followed by Malawi (4.62%). These high fatality rates owe to the small number of cases that are mostly captured (tested) when persons report signs and symptoms or present themselves at medical facilities sick. There is no broad testing. Currently, half of the countries of the region have less than 2% fatality rate. These countries are Lesotho, Zambia, Eswatini, Namibia, Mozambique, and South Africa.

Policy dilemmas: how Africa’s lockdown preventative and containment measures for the pandemic were implemented

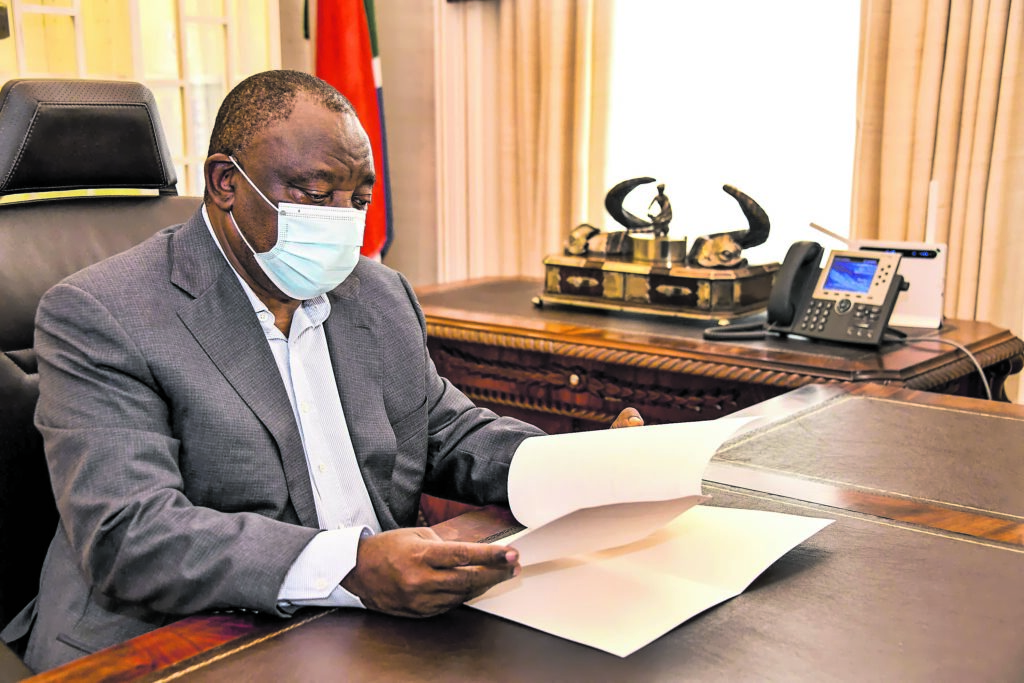

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who is also the Chairperson of the African Union, announced the first lockdown in March 2020, which was later extended. (Photo: Baba Jiyane)

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who is also the Chairperson of the African Union, announced the first lockdown in March 2020, which was later extended. (Photo: Baba Jiyane)

The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) report on Africa’s governance response to COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted at its core the issue of preventive and containment measures.

The preventive and containment measures include total or partial lockdowns, which have either been applied to entire countries or only parts thereof.

Take South Africa, for instance. Since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in South Africa on 5 March 2020, the national government has taken steps to minimise the spread and impact of the virus.

On 18 March 2020, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Minister of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, issued regulations to prevent an escalation of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa.

On 23 March 2020, nine days after detection of the first locally transmitted case, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a nationwide 21-day lockdown. On 9 April 2020, the President extended the lockdown for a further two weeks. The lockdown restrictions were among the most extreme globally.

According to the report, the duration of these lockdowns varies, ranging from 10 days in Libya, for example, to indefinite, as is the case in South Africa, although here the government periodically scales down the applicable preventive and containment measures.

These lockdowns entail the closure of schools; the banning of public gatherings, including religious gatherings in most cases, (Tanzania was an exception); restrictions of movement and the closure of businesses, save for providers of what the government declares to be “essential services,” which included transport services, essential food and medicine production and retail operations, health workers, and those who maintain key infrastructure such as power, water and sanitation.

Some countries have established thresholds for public gatherings. In Zambia, for example, a meeting of less than 50 people is not considered a public gathering.

“It should also be noted that what amounts to essential services may vary from country to country. In some countries, such as Egypt and Kenya, the preventive and containment measures also entail dusk-to-dawn curfews, which again are either imposed nation-wide or only in regions or localities considered to be most affected,” states the report.

“Countries such as Algeria have imposed total lockdowns in their most affected areas or provinces, while permitting free movement in other areas. Conversely, countries such as Egypt and Ethiopia have imposed nation-wide curfews. Unlike most countries, Tanzania has imposed the least restrictions on its citizens. Here, government and private enterprises continue to operate normally.”

Invariably, the prevention and containment measures have either been preceded, or accompanied by declarations of national states of emergency, or national disaster, as in the case of Malawi and South Africa, or national alarm as in the case of Equatorial Guinea. The result is that most countries are under both states of emergency and lockdowns.

Countries have also closed their borders, particularly with a view to reducing their exposure from high-risk countries.

In addition, countries such as Uganda have suspended refugee reception services, says the report.

Other commonly used containment measures are quarantines, the tracking and tracing of the contacts of infected persons, the encouragement of social distancing, encouraging citizens to wash their hands frequently, and the wearing of protective and preventive equipment such as face masks.

With respect to hand washing, the report notes, Sierra Leone has installed hand washing stations in many of its health facilities, markets and schools.

The quarantines are administered in different ways. In some cases, the affected individuals are required to self-quarantine. In other cases, they are quarantined in government facilities or hotels, either at their expense or at the expense of the government.

For example, in Kenya and Ethiopia, affected travellers are quarantined at their own expense. A common challenge, however, is that the affected travellers may not be able to afford the quarantine expenses. In addition, requiring infected persons to meet the quarantine costs may be counterproductive, as it could discourage people from getting tested.

Another challenge for member states has been ensuring the availability and accessibility of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Egypt has sought to resolve this challenge by tasking its state-owned enterprises linked to the military to produce the required preventive and protective equipment.

Similarly, Mozambique has sought to redirect its industrial sector toward the production of goods required for the prevention and mitigation of the pandemic.

As far as treatment of those suffering from COVID-19 is concerned, Cameroon has established specialised treatment centres in its regional capitals. Senegal is also spearheading the development of affordable ($1) testing kits, working with its research institutions.

The disease containment and prevention measures have implications for citizens’ enjoyment of human rights. For example, quarantines may have adverse impacts on the ability of vulnerable groups to earn a living (since they are likely to lose their jobs as they cannot go to work) and access basic necessities such as food and healthcare.

Such groups also often do not have access to social security, and so measures such as quarantines are likely to have harmful consequences for them.

These measures should therefore be imposed and implemented within a framework that respects the rule of law and the human rights of citizens.

In this respect, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights permits states to take measures that deviate from their obligations under this covenant in emergency situations.

However, the covenant only permits such deviations when a state officially proclaims a state of emergency and the measures it proposes are proportional, meaning that they are strictly required by the exigencies of the emergency.

The covenant prohibits deviations from certain fundamental rights, including the right to life, prohibition of cruel or inhuman punishment, and the principle of legality. In contrast, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights does not allow member states to deviate from their treaty obligations during emergency situations.

In countries such as Kenya and Malawi, the courts have therefore ruled that declarations of states of emergency must be made within the framework of the law, and that the use of force in enforcing curfews is unreasonable and security forces need to respect citizens’ rights to life and dignity.

These courts are also insisting that individuals who are being temporarily held in quarantine are to be treated at all times as free agents, except for the limitations necessarily placed upon them in accordance with the rule of law and on the basis of scientific evidence.

Thus, the containment and prevention measures should not constitute punishment. Further, member states need to ensure that these measures are implemented in a manner that does not undermine livelihoods, particularly of vulnerable populations. — Charles Molele

Case Studies

NAMIBIA

Since the first recorded case on 13 March 2020, the government of Namibia has moved swiftly to implement measures that counter the spread of the virus. National efforts to contain the virus began by the declaration of a State of Emergency on 17 March 2020 and adaptation of other containment measures. These include the establishment of isolation treatment facilities, 14 days of mandatory quarantine, a community awareness campaign, a call centre to report suspected cases of COVID-19, as well as contact tracing, and a once-off grant payment to the most vulnerable.

Despite having one of the lowest infection rates so far on the continent, the government of Namibia has also rolled out economic stimulus and relief packages to mitigate the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic.

These include direct support to business, households and the labour market; support to the hardest-hit sectors, namely travel, tourism, aviation and construction; and a food and water subsidy. In addition, the government has directed the private sector to ensure no retrenchments of workers takes place during the lockdown period.

The government has also unveiled plans for free water and a food subsidy during the lockdown, to ensure that all Namibians have access to food and potable water during the lockdown, and in order to ensure that public hygiene is maintained.

TOGO

Togo has been proactive in combating the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country by instituting the following measures:

• A two-week suspension, with effect from Friday 20 March 2020, of all flights from high-risk countries: Italy, France, Spain and Germany;

• The issuance by the president of the Republic of a decree establishing an inter-ministerial body to manage the health crisis caused by COVID-19, known as the National Coordination for Response Management in Togo (CNGR COVID-19).

• The establishment of a local response management committee, which reports to the national co-ordination body;

• The dedication of a hospital (CHR Lomé Municipality) to patient care, as well as a hotel in the capital for quarantine;

• The creation of a five-thousand-man strong special anti-pandemic force;

• The establishment of mobile laboratories for screening within the country;

• The launch of a cash transfer programme for the most vulnerable, called Novissi; and

• The introduction of specific support measures to sustain agricultural production and ensure food self-sufficiency, and the establishment of a National Solidarity and Economic Recovery Fund of 400-billion CFA francs.

Humanitarian impact of COVID-19 Pandemic – APRM Report

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on African economies. In countries where there are conflict zones, this effect has been exacerbated, and international aid or grants have been requested to help the most vulnerable. (Photo: Kate Holt/Unice)

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on African economies. In countries where there are conflict zones, this effect has been exacerbated, and international aid or grants have been requested to help the most vulnerable. (Photo: Kate Holt/Unice)

By all accounts, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a global threat for the least developed or most vulnerable countries, and poses an additional level of risk to an already complex situation.

The outbreak has wreaked havoc on states in west and central Africa where conflict, violence, displacements of population, natural disasters, climatic or economic shocks have weakened the resilience capacity and where systems are on the verge of collapse.

The pandemic is definitely not just a health crisis and its impact has devastated the region, putting millions at risk and requiring an urgent scale-up of inter-sector support and resources.

Mali dedicated $10.4-million to dealing with the pandemic while Togo established a $663-million National Solidarity and Economic Relief Fund to support agricultural production and ensure food security.

Countries such as Angola, Djibouti, Mozambique and the Republic of Sudan have substantially increased their healthcare spending to respond to the coronavirus and are granting tax exemptions for humanitarian aid and donations.

According to the APRM report, various countries have established special funds to help them manage the social and humanitarian impacts of the pandemic.

South Africa established special funds to cater for workers with an income below a certain threshold for the duration of four months, assist SMMEs under stress — particularly the tourism and hospitality sectors — and help the most vulnerable members of society to absorb the economic impact of the pandemic.

Several other countries, such as Sao Tome and Principe, have received grants from international institutions such as the World Bank to fund their emergency responses.

Kenya received funding from the World Bank, as a contribution to its COVID-19 Emergency Response Project Fund. Zimbabwe also launched a domestic and international humanitarian appeal for $2.2-billion to cater for the pandemic, including critical health spending, water and sanitation, hygiene, food security and social protection.

Morocco and Tunisia have tasked their national social security institutions with responding to the vulnerabilities introduced by the pandemic. Their strategic monitoring committees support employees who are registered with national security institutions. They also assist the vulnerable, particularly those in the informal sector, who are vulnerable to shocks and require economic, social or medical protection.

Egypt has extended social protection to support vulnerable families while Ghana has suspended the payment of utility bills for a period of three months, which terminates in June 2020.

Ghana has also established a Coronavirus Alleviation Program, which is a social protection initiative that seeks to support vulnerable households and SMMEs.

Some governments, such as Botswana and Lesotho, issued subsidies to supplement the wages of workers in the private sector affected by lockdowns.

According to the report, the Republic of Sudan is considering boosting its social safety net by $1.5-billion within three months. It has also announced a significant increase in the salaries of public sector employees and dedicated funds to support families affected by lockdown measures.

Togo has also launched a money transfer program to help citizens most affected by the crisis. It is also providing vulnerable social groups with free water and electricity for a period of three months.

CASE STUDY

COVID-19 Fund for SMMEs in Ghana

Soon after the confirmation of its first COVID-19 case on 12 March 2020, the Republic of Ghana, under the leadership of Nana Akufo-Addo, put in place a series of measures to curb the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

These measures include banning travel into Ghana; restrictions on movements; resourcing research and testing laboratories; and social interventions.

On 30 March 2020, the president announced the imposition of partial lockdown for an initial period of two weeks from March 30. After its extension by one more week, the lockdown was finally lifted on 19 April.

Additional measures include the local production and supply of personal protective equipment, enhanced surveillance, intensive contact tracing and laboratory testing, and public education.

The government established a COVID-19 National Trust Fund aimed at assisting the needy and the most vulnerable in the society.

The Ghanaian private sector also set up a COVID-19 Fund worth GHc100-million to complement the efforts of government. As part of its support to small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs), the government has allocated the amount of GHc600-million (about $109-million) in soft loans to SMMEs to sustain the country’s affected industries.

The president initiated a national dialogue with key national stakeholders, opposition political parties, organised labour and health professionals among others, to jointly discuss a co-ordinated approach in the fight against the deadly virus.

Fiscal and monetary measures in response to COVID-19 crisis: Strengthening confidence and resilience

South Africa’s Reserve Bank. The bank has accelerated reimbursements and tax credits, among other measures. Several African countries have introduced similar policies to provide some financial succour to businesses and consumers during the pandemic. (Photo: Alet Pretorius/Gallo Images)

South Africa’s Reserve Bank. The bank has accelerated reimbursements and tax credits, among other measures. Several African countries have introduced similar policies to provide some financial succour to businesses and consumers during the pandemic. (Photo: Alet Pretorius/Gallo Images)

Most African Union member states are implementing various fiscal and monetary policies to manage the pandemic and its economic impacts.

Through various measures, countries are helping businesses stay afloat, supporting households and helping to preserve employment.

South Africa’s Reserve Bank has accelerated reimbursements and tax credits and allowed SMMEs to defer certain tax liabilities. It has also reduced the lending rate by 100bps to 4.25% and instituted measures to ease liquidity strains in funding markets, while the government has launched a unified approach to enable banks to provide debt relief to borrowers.

In April 2020 President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that other measures included the release of disaster relief funds, emergency procurement, wage support through the UIF and funding to small businesses.

“We are now embarking on the second phase of our economic response to stabilise the economy, address the extreme decline in supply and demand and protect jobs,” said Ramaphosa.

“As part of this phase, we are announcing this evening a massive social relief and economic support package of R500-billion, which amounts to around 10% of GDP.”

Egypt announced a $6.13-billion relief package, part of which is intended to support its health and tourism sectors. It has also postponed the payment of real estate tax for three months, lowered energy costs for industries, lowered interest rates by 300 points, and postponed debt repayments by six months for firms and individuals alike.

“The package of decisions taken by the government reflects its determination to quickly support the industrial sector and confront [the] current repercussions,” Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly said in a cabinet statement.

Similarly, Tunisia has established an emergency package plan that entails the postponement and exemption of debt payments, and the rescheduling of taxes for low-income individuals. Angola has postponed the filing of taxes.

The Reserve Bank of Malawi deferred interest rate payments and imposed a three-month moratorium on interest and principal repayments for loans for microfinance institutions and financial co-operatives.

Namibia has launched an Economic Stimulus and Relief Package to meet increasing expenditures in health, wage subsidies, income grants, and guarantees to support low interest loans for small agricultural businesses and individuals.

Among others, Senegal has dedicated $490-million towards those economic sectors directly affected by the pandemic, including tourism, transport and agriculture. Part of these funds are being used to pay the salaries of retrenched staff. Cote d’Ivoire is facilitating the postponement of debt repayments, particularly for SMMEs.

The Gambia Revenue Authority has extended the filing and payment of 2019 taxes by two months. Senegal has escalated tax refunds to companies, deferred payment of taxes for small, medium and micro enterprises up to 15 July 2020 and provided support through the renewal of all fixed-term contracts.

In East Africa, Kenya’s central bank has lowered its policy rate by 100bps to 7.25% and lowered commercial banks’ cash reserve ratio by 100bps to 4.25%.

It has also increased the maximum tenor of repurchase agreements from 28 to 91 days, announced flexibility for banks regarding loan classification and provisioning for loans that were performing up to 2 March 2020 but were restructured due to the pandemic.

Further, Kenya suspended the listing of negative credit information for borrowers whose loans became non-performing after 1 April 2020 for six months, and encouraged commercial banks to extend flexibility to borrowers’ loan terms.

Kenya’s measures include full income tax relief for persons earning below the equivalent of $225 per month, and reductions of the top pay-as-you- earn rate from 30% to 25%, lowered the base corporate income tax rate from 30% to 25%, the turnover tax rate on small businesses from 3% to 1%, and the standard VAT rate from 16% to 14%.

The Bank of Uganda has reduced its Central Bank Rate (CBR) by 1 percentage point, directed Supervised Financial Institutions (SFIs) to defer payments, provided liquidity to commercial banks, purchased treasury bonds held by microfinance deposit-taking institutions and credit institutions, and granted exceptional permission to the SFIs to restructure loans of corporate and individual customers. It has also issued guidelines for the SFIs on credit relief and loan restructuring.

The Gambia’s central bank has increased its monitoring of commercial banks’ forex net open positions and committed to maintaining flexible exchange rates to absorb balance-of-payments shocks. Many of the central banks are also increasing their financial surveillance.

Many countries have established special funds to manage COVID-19 and its impacts. Tunisia has established a special fund for businesses that the pandemic has affected significantly, while Botswana has established a relief fund and seeks to stabilise businesses and ensure the availability of strategic supplies.

Lesotho has set up a Contributory Fund and is using it to pay a subsidy to affected textiles workers, pay business rentals in May 2020 and defer certain taxes until September 2020, as well as improve credit facilities for SMMEs.

Zambia established an emergency fund to strengthen its preparedness and enhance public security during the pandemic. Ethiopia is planning to support enterprises and job creation in urban areas and industrial parks.

It is also working to expand its Urban Productive Net Program in collaboration with the World Bank. Cote d’Ivoire has established a $490-million fund to support communities and corporations. Ghana has established a $1.5-million National Trust Fund.

Countries are also bolstering their financial and banking sectors. Various central banks have sought to ease liquidity conditions by reducing reserve requirements for banks and easing payment system transactions.

Angola’s central bank, for example, has reduced the rate on its seven-day permanent liquidity absorption facility by 3%, provided about 0.5% of its GDP as liquidity support to banks, and created a liquidity line equivalent to $186-million for the purchase of government securities from non-financial corporations.

Zimbabwe has reverted to a multicurrency system, reducing the bank policy rate from 35% to 25%, reducing the statutory reserve ratio from 5% to 4.5%, and increasing private sector lending facilities from ZW$1-billion to ZW$2.5-billion. Its central bank has also moved from a managed floating exchange rate system to a fixed exchange rate management system.

The Bank of Uganda is providing exceptional liquidity assistance for a period of up to one year to financial institutions that need it, ensuring that the contingency plans of supervised financial institutions guarantee the safety of customers and staff. It has also instituted measures to minimise the likelihood of sound businesses going into insolvency due to lack of credit, and waiving limitations on restructuring of credit facilities at financial institutions that may be at risk of going into distress.

Yet another significant set of measures relates to taxation. In this respect, several governments have imposed various tax relief measures.

To minimize the use of bank notes, the governments of various AU member states such as Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia have persuaded mobile money operators to either reduce or remove user fees and charges for periods of about three months. These countries have also lowered fees and charges for other digital financial transactions.

There are also cases of innovation happening across the African continent that should be recognised. An example is the Senegalese Ministry of Health, which, in collaboration with the Virology Laboratory of the l’Institut Pasteur de Dakar, created the $1 COVID-19 diagnostic testing kit. — Charles Molele

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on constitutionalism and the rule of law

The government of Benin has been particularly proactive in the fight against COVID-19. It purchased 30-million surgical masks and made them available to the public at subsidised pharmacy prices, and screening for the virus has been widespread. (Photo: Yanick Folly/AFP)

The government of Benin has been particularly proactive in the fight against COVID-19. It purchased 30-million surgical masks and made them available to the public at subsidised pharmacy prices, and screening for the virus has been widespread. (Photo: Yanick Folly/AFP)

The APRM report has compiled an interesting overview of the COVID-19 situation with regard to constitutionalism and the rule of law.

AU member states have either deployed existing legal and institutional mechanisms or established new ones to respond to the pandemic.

The mechanisms thus introduced focus on i) legal and institutional measures; ii) disease prevention and containment measures, iii) social and humanitarian measures; and iv) fiscal and monetary measures.

The report investigates the effectiveness of these measures, in terms of the following: ensuring desirable outcomes; impacting the enjoyment of human rights; ensuring equal treatment of citizens; and facilitating the accountability of government to the public.

According to the report, the legal and institutional mechanisms deployed by African states in the management of the COVID-19 crisis have included national scientific commissions, monitoring committees, emergency committees and inter-ministerial committees. Several countries have also developed preparedness and response plans.

Some countries, such as Malawi and South Africa, have laws (national legislation) on disaster preparedness and management, although it is not clear thus far whether or how they are deploying these laws to manage the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the most part, African states have established ad hoc legal and institutional mechanisms to respond to the pandemic. For example, Algeria has used its national scientific commission to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, while Mozambique has established an advisory technical and scientific committee.

Other countries such as Morocco, Nigeria, Togo and Tunisia have established strategic monitoring committees, crisis committees or co-ordination mechanisms.

Yet other countries such as Chad, the Republic of Sudan, Lesotho and Uganda have developed preparedness and response plans. Some countries have also established ministerial or inter-ministerial committees to co-ordinate their responses to the pandemic.

In Uganda’s case, the ministry of health is spearheading the implementation of the country’s Preparedness and Response Plan while in Djibouti the ministry of health is enhancing its preparedness to deal with the pandemic by building its capacity for surveillance, testing and quarantines. It is also building the capacity of health workers.

The Republic of Sudan has developed a Multi-Hazard Emergency Health Preparedness Plan, which is co-ordinated by a high-level emergency committee. Chad has established a Health Monitoring and Safety Unit, which the presidency co-ordinates.

The rule of law and the role of public institutions in a country’s preparedness and resilience in the context of the COVID-19 crisi is pivotal.

The manner in which national public institutions have acted with effectiveness, transparency, sharing information and accountability in Africa reflects a stronger societal value inclination towards inclusiveness.

Although African countries have been constantly criticized for being poorly governed, Africa’s governance responses to COVID-19 indicates, to a great extent, a much better degree of institutional preparedness than had been previously assumed.

This positive comparative difference between developed and developing countries notwithstanding, it is apparent that many member states lack the requisite legal and institutional mechanisms to handle crises of the magnitude of COVID-19.

In order to be effective, legal and institutional mechanisms need to be inclusive and consider the needs of all stakeholders, particularly the vulnerable members of society.

These mechanisms should also be accountable to the public for their decision-making, including reporting on the use of public resources and informing the public of their policies and actions.

Public participation and accountability are also critical as they help to build social trust, without which affected publics may not comply with measures instituted to manage the pandemic and its impact.

There is strong evidence that the one-size-fits-all model of quarantine/lockdown models may not be the foremost effective response to the pandemic. — Charles Molele

CASE STUDY

Surgical masks in Benin

Benin has been proactive in preventing the spread of COVID-19 pandemic in the country. Instituted measures include:

• Setting-up of an ad hoc inter-ministerial committee for the management of the health emergency associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and a committee of experts on the coronavirus;

• Activation of the National Health Crisis Committee (CNCS) and the strengthening of health surveillance at all points of entry to the country, particularly at Cotonou Airport and Port;

• Thirty-million surgical masks were acquired by the government during the period and made available to the population at subsidised pharmacy prices. In addition, public transport operators were implored to provide their employees and passengers with appropriate masks or bibs;

• The government has authorised the provision of chloroquine at a subsidised price to pharmacies throughout the country and to the essential drug dispensing units of public health facilities, with a view to optimising therapeutic care in the best safety and control conditions. This therapy has been recommended on the basis of scientific evidence and evidence-based findings by the government-appointed expert medical committee;

• A decision was taken to systematically screen communities at risk, in particular medical and paramedical personnel, security and defence forces personnel and the prison community, effective since 27 April 2020.

Recommendations: Africa’s governance response to COVID-19

The APRM report recommends that the African Union establishes a Continental Solidarity Fund to assist member states when large-scale crises occur, among a host of other measures to help countries prepare for future disasters. (Photo: Sumy Sadurni / AFP)

The APRM report recommends that the African Union establishes a Continental Solidarity Fund to assist member states when large-scale crises occur, among a host of other measures to help countries prepare for future disasters. (Photo: Sumy Sadurni / AFP)

The APRM report contains recommendations to member states around, among other things, on how to scale up COVID-19 testing, and maintain essential health services during the outbreak.

Recommendations for the African Union (AU):

1. AU must advise member states on modalities for conducting elections during the pandemic in a manner that ensures credible, free and fair elections during the pandemic. The principles obtained should also be integrated into the Guidelines for AU Electoral Observation and Monitoring Missions. The commission should support member states to establish electronic elections systems.

2. The AU should revise Agenda 2063 to emphasise disaster preparedness and management in its member states.

3. The AU should develop a continental framework on disaster preparedness and management, and encourage its member states to incorporate this framework in their national and local development frameworks.

4. The AU should encourage its member states to sign and ratify the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Treaty, which provides a framework for disaster early warning and contingency planning, and disaster insurance for participating states. Member states are also encouraged to invest substantially into the ARC Insurer.

5. AU should develop guidelines for multinational enterprises to support responsible business conduct to ensure that a co-ordinated and structured platform for business and government and/or AU collaboration is put in place beyond COVID-19.

6. The AU should establish a Continental Solidarity Fund to assist member states when large-scale disasters such as COVID-19 occur, and co-ordinate the management of such disasters.

7. The AU should assess the scientific, technological and institutional capacities of its member states, including their capacities for vaccine research and development, with a view to contributing to enhancing their ability to prepare for and manage disasters.

8. The AU should fast-track the adoption of a policy framework of mechanisms for “APRM Support to Member States in the Area of Credit Rating Agencies” currently awaiting final validation by the AU Special Technical Committee of Ministers of Finance, Monetary Affairs and Regional Integration; and it should call for a moratorium on rating downgrades of developing countries based on the COVID-19 outlook.

The headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa. (Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images)

The headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa. (Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images)

Recommendations for member states:

A) Immediate governance measures

1. Member states should establish multi-stakeholder national response governance bodies.

2. Member states should ensure that their COVID-19 prevention and containment measures are implemented within a framework that respects the rule of law and the human rights of citizens.

B) Medium-Term Governance Measures

1. Member states that do not have national disaster-related legislation and a relevant institutional mechanism should consider these measures for implementation as best practice.

2. Member states are encouraged to increase their investment in institutional capacity central to an effective governance response to COVID-19.

3. Public institutions and the private sector should accelerate south-south co-operation for knowledge sharing, technology transfer in healthcare, and epidemics research.

4. Member states should incorporate disaster planning in their national and local development planning frameworks. 5. Member states should decentralise responsibilities and capacities for disaster management and ensure co-ordination and co-operation between the local and national levels.

6. Member states should adopt a human rights approach to disaster preparedness and management and ensure their governments consider the potential consequences of their disaster policy decisions and actions for the enjoyment of human rights by all concerned.

7. Member states should establish mechanisms for ensuring that their governments are accountable for disaster decision-making, including in the use of public finances devoted to the emergencies that disasters create.

8. Member states should, as far as is possible, invest in developing the infrastructure and scientific, technological and institutional capacities to research and forecast hazards, vulnerabilities and disaster impacts, including developing capacities for vaccine research and development.

Recommendations for the APRM

1. Undertake research on state resilience and disasters to inform its methodology and processes.

2. Review APRM framework to integrate disaster preparedness and management, including revising its base questionnaire to address the governance of disasters.

3. Develop monitoring and evaluation tools for evaluating the attainment of good disaster governance.

To see the French version of this, click here