It’s important to put science, natural science, human sciences and social sciences at the forefront of discussions about the Covid-19 pandemic, to get the facts out there

The role of the social sciences in a strong Covid-19 response

While the natural and medical sciences have arguably been the star of the world’s response to Covid-19, the social sciences and humanities offer invaluable insights for a fuller understanding of how the pandemic has affected people.

Buti Manamela, the Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Science, and Innovation emphasised that epidemics impact people and society in complex ways and one should not expect only one scientific discipline to fully accurately anticipate or respond to the challenges.

“It is for this reason that an approach that seeks to draw from the wisdom of all scientific disciplines is the most sensible one.”

He was speaking at a recent ministerial plenary session during the 2021 edition of Science Forum South Africa (SFSA), which brought together a variety of experts to discuss how the humanities and social sciences can be integrated into the country’s pandemic response.

Manamela explained that multidisciplinary approaches are a core part of this. “We’ve seen how co-operation between different and various branches of science have collaborated in helping us not only understand the pandemic, but also its impact and societal responses in what the government and various role players introduce as remedy and as intervention.”

Professor Yonah Seleti, the Acting Deputy Director-General of Research Development & Support at the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI), added that the department’s minister made it an important part of the process in fighting the pandemic to involve the social sciences. This advocacy was championed by the likes of the Director General of Science and Innovation, the Statistician General and and then the Commissioner of the South African Revenue Services.

Manamela said that scientific interventions and research must also be culturally appropriate. “Often, the reason why potentially useful scientific solutions do not get put in place by communities is because such communities often view the work of scientists and researchers as having no regard for their cultural norms and values.“ He said that this is particularly important, given that pandemics should not place further burden on the more vulnerable parts of society.

The Director of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, Shane Norris, said that across the different types of data collected during the pandemic, there has been a profound impact. “A part of where I think social scientists can really help is how do we start looking at recovery solutions and potentially shifting our focus to recovery, and feeding that evidence and insight back in.”

Professor Priscilla Reddy, a visiting scholar at the Centre for Critical Research on Race and Identity at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), said that the fact that socio-behavioural research was undertaken by the HSRC from the start of the pandemic is laudable.She thanked the DSI and others “for actually realising the importance of social science research and its application and [bringing] us in from the outset.”

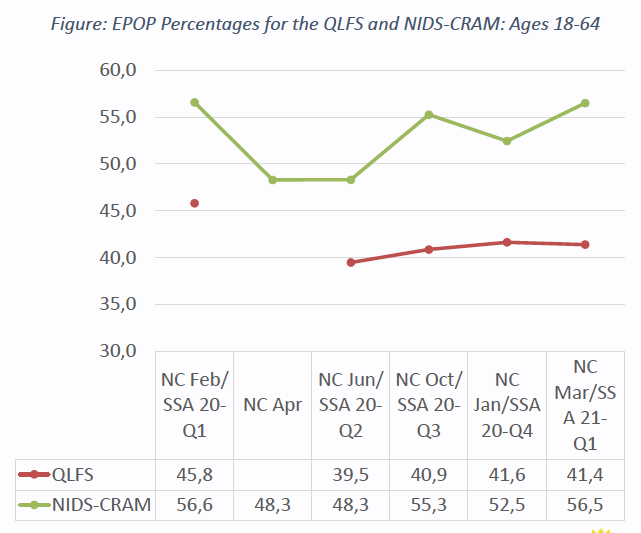

Professor Reza Daniels, from the school of economics at the University of Cape Town, said that socio-economically focused surveys allowed the government to have a view on the pandemic that was beyond just the health or epidemiological data.

He explained that the National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) showed that some of the early government interventions were too onerous at the time and that more nuanced approaches are necessary.

Socio-economic studies also give realistic insights, albeit often in hindsight. Daniels said: “You need them because they provide actual data as opposed to the projections that epidemiologists will be able to offer.” Hence, a joint-modelling approach is key.

Daniels said that this affects the future. “The lesson we must take from Covid-19 is that with future pandemics — everybody is telling us that there will be more of these, more often — we will in fact need to be able to do so and have multidisciplinary modelling to understand the response.”

Reddy agreed, saying that the data gathered during the pandemic by researchers and scientists should do more than just inform policymakers.

“I think that was really important and relevant at the time,” she said. “However, I think the application of social science research and data collection needs to be re-examined. “It should serve to pave the way for interventions in the fields of health, education, and social and behavioural issues.”

Reddy saId: “We know that outbreak, control and management of pandemics needs to be pivoted on a philosophy of working for the common good, and I don’t think we can work for the common good in single in single silos.”

Professor Narnia Bohler-Muller, Acting Group Executive: Shared Services & Divisional Executive: Developmental, Capable and Ethical State, said that while there are a variety of perspectives and opinions, the scientific research of all disciplines should be the leading light in crisis situations.

“There are many cultural, religious and individual views of what is happening in terms of the pandemic,” she said, “but it’s important to put science, natural science, human sciences and social sciences at the forefront of these discussions so that we can get facts out there and perhaps change minds, if minds are open to change.”

Be ready for the unexpected

The Covid-19 pandemic was a challenge for the scientific community in South Africa like few others, but the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) stepped up in an innovative way.

Professor Yonah Seleti, the Acting Deputy Director-General of Research Development & Support at the DSI, said that the DSi was ready in terms of facing the pandemic.

Buti Manamela, South Africa’s Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Science and Innovation

Buti Manamela, South Africa’s Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Science and Innovation

Seleti explained that there were structures in place to lead the way when the pandemic hit. This was firstly on the policy level, where the White Paper on Science, Technology and Innovation paved the path for interventions during the pandemic. It focuses on co-ordination, partnerships, and transdisciplinary socio-technical systems that go beyond what just the DSI does.

Moreover, there were investments made into the National System of Innovation and into the terms of leadership of the NSI, and in Cabinet more broadly. Seleti said that this laid a foundation to start and continue from when the pandemic started.

“When the outbreak of the virus happened, the initial focus of the work was more on understanding the science of the virus and more on the epidemiological part, and this is where leadership matters.”

Buti Manamela, Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Science, and Innovation, said that science has been critical at this time.

“There is certainly no doubt that the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic has heightened our consciousness of the important role that science is playing in improving the quality of life of ordinary people.”

The Director of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, Shane Norris, said that the research work over the last 18 months has shown that business cannot just carry on as usual. One area for improvement is to become faster in the process of data collection, analysis and dissemination.

“We need to be better prepared, but the partnering with the government we’ve been doing up till now is a brilliant start; we should continue to ensure we have alignment and preparedness for potentially the next pandemic.”

On a hopeful note, Norris said that the platforms for research currently in place are rather phenomenal. “That kind of investment in these initiatives is something we need to really gain more from and potentially a greater, co-ordinated, galvanized approach to all this infrastructure in future endeavors may be something that can exponentially add value.”

An observatory of observatories

Accurate and updated data has played an important part in shaping the unfolding of the Covid-19 pandemic, but correlating and consolidating all of it from different sources is no easy feat. This unprecedented time has given birth to one government-led organisation that is doing just that — for now and for the future.

The National Policy Data Observatory (NPDO) brings together a variety of types of data and statistics to monitor and understand them better, in an effort to affect good decision making.

The NPDO allows for a central point in an ecosystem where data exists on a variety of different platforms, from StatsSA to medical databases

The NPDO allows for a central point in an ecosystem where data exists on a variety of different platforms, from StatsSA to medical databases

It has been running for almost two years and is currently incubated at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). A part of this is the Data and Decision Support Centre, which collects and stores data and releases a variety of analytics, trends, and dashboards.

Dr Jabu Mtsweni, Manager of the Information and Cyber Security Research Centre at the CSIR and the technical leader of the NPDO, said a lot of good work has already been done by the observatory.

“The data observatory is trying to fill that gap, where we pull everything together so it is accessible in one area.”

The Data and Decision Support Centre has the capability to work on a wide range of activities, but the key focus at the moment is — unsurprisingly, given the origins of the NPDO — to give data insights on Covid-19, on provincial, district and national levels.

This includes trends, analytics, models and strategies, and rolling averages, but also monitoring of hospitalisations and mortality. Global movements in terms of vaccinations, variants and the pandemic more widely fall into this category.

The work also tries to anticipate future trends by forecasting surges in Covid-19 cases and waves, particularly in terms of where hotspots may develop. For instance, Mtsweni explained that the development of different waves of the pandemic can easily be compared.

However, the capabilities expand far beyond this. To name one, profiles of particular districts, including rural districts, can give a clear view of demographics, service delivery trends, educational services, and district financial status. The centre can also monitor mobility patterns, for instance to understand lockdown compliance.

An interesting area of data monitoring is the analysis of social sentiments, where social media data is used to measure the national mood around issues. This can reveal where there is pandemic fatigue, spreading of misinformation or even the development of unrest.

“You can clearly see that the National Policy Data Observatory’s work is very broad and diverse, and we continue to grow,” Mtsweni said.

All of these insights have already been used in places such as the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Vaccination, the Department of Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluation, and the Government Communication and Information System (GCIS).

The active contributions include weekly reports to the National Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure (NATJOINTS), which co-ordinates security and law enforcement operations. Importantly, the national Department of Health is supplied with secondary data analysis.

The NPDO has created a variety of databases of statistics, some of which are hosted by the Centre for High Performance Computing at the CSIR.

“I think what makes the data observatory central is we are an observatory of observatories, because the other institutions will still do their work and collect that data,” said Mtsweni. He explained that they look beyond the borders of South Africa at global trends and tracking development indicators such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Mtsweni explains that this kind of work can be instrumental in informing decision-making processes. “When we deal with data and integrated data, it has the capacity to make us get ahead in our decision making. Also, it assists us to be forward thinking but to also have insights that generally we did not have when we didn’t have this data.”

Another strong suite of data observatories is that they can have a multi-dimensional approach, which integrates and correlates different kinds of information. Mtsweni gave the example that during Covid-19, health data could be combined with other data sources, such as economic, governance and social impacts.

An observatory like the NPDO allows for a central point in an ecosystem where data exists on a variety of different platforms, from StatsSA to medical databases. Mtsweni named datasets such as population statistics, service delivery numbers, and the monitoring of movements and security.

“That data alone just gives you a snapshot, but when you combine it with the social economic data, it then gives you a much better idea so that you can make decisions in a risk-based approach, because every decision that we take, whether it’s about restrictions or vaccinations, has its pros and cons.”

Ashwell Jenneker, Deputy Director-General of Statistical Operations and Provincial Coordination at Statistics South Africa, said: “I think the National Policy Data Observatory has achieved more in this last year than I’ve achieved in my 23 years at StatsSA in terms of promoting and making sure that people make evidence-based decisions. Very well done!”

Risenga Maluleke, Statistician-General and the head of Statistics South Africa, said participants from across government and the private sector, such as the actuarial Society of South Africa, have contributed to the project. He encouraged other stakeholders to take part where possible. “It is working, and it is being institutionalised, and it’s institutionalisation doesn’t only rest on us being members, but in making sure that we put as much data on this platform as possible.”

In terms of the future, Professor Priscilla Reddy from the Center for Critical Research on Race and Identity at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) said that the focus should go beyond surveillance and collecting data. “I think the observatory’s next challenge would probably be to look at a component of implementation science, because the data is being translated for policy, but I think we need to drill down to that detail and look at how we develop these interventions that are targeted, that are strategic, that are focused culturally and linguistically relevant.”

While the NPDO is a powerful tool during the current crisis, Mtsweni explained that from the start of the project, its future possibilities were considered. “The Covid-19 pandemic is a springboard, but we see this as a facility and is an initiative that is government-led that informs policy, but over and above that, it provides insights on various socio economic indicators.”

Forum discusses science for South Africa

Much of the content on these pages originated from discussions during the latest edition of the Science Forum South Africa (SFSA). This event is a highlight on the calendar of science events in the country and brings together experts from near and far to discuss how science, technology and innovation can make a difference in the challenges faced by the world today.

Conversations about science were ignited at this year’s SFSA in order to strengthen pandemic preparedness through knowledge transfer

Conversations about science were ignited at this year’s SFSA in order to strengthen pandemic preparedness through knowledge transfer

The theme of SFSA 2021 was Ignite Conversations about Science, inviting discussion and reflection to start with the many scientific inputs that our country has to offer.

This year’s event, held in early December, took place in a hybrid mode. It was convened partly online and partly at the CSIR International Convention Centre (ICC) in Pretoria. The SFSA has been taking place since 2015.

The discussions across dozens of parallel sessions debated topical issues of science and innovation that are important to the world now, from the Covid-19 vaccination landscape in Africa and strengthening pandemic preparedness through knowledge transfer.

Topics also focused on the environment, diving into smart, green and sustainable transport partnerships and the future of South Africa’s hydrogen economy.

The SFSA is hosted by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and is a launchpad for interesting ideas and discussion. More content about this year’s SFSA can be found online, including at www.sfsa.co.za

Where does the data come from?

Ordinary South Africans may look at the case numbers of how many people have been tested or found positive for Covid-19 in the last day or so as a key indicator of how the pandemic is progressing and how our country is responding.

But, there are far more sources of information that can help inform decisions about the state of health in the country and managing Covid-19 health outcomes of various kinds. There is also the socioeconomic data ecosystem, which may affect how the country is able to respond more broadly.

Information centres such as the National Policy Data Observatory (NPDO) are monitoring these to bring them all together into a clear picture.

Here’s how…

The health data ecosystem

Prediction and early warning

To understand the demand for healthcare and the capacity that the health system might have, scientists look to case detection and capacity data. This might come from labs, test centres and the monitoring of Intensive Care Units (ICUs).

Social graph making

Knowing where people are meeting regularly and understanding these movements better can inform health interventions, which information from cellphone towers and geospatial data can provide.

Flow modelling

Knowing how many people pass through a certain place at a given time and how quickly can also be helpful in monitoring the flow of people, as it affects Covid-19 infection rates. Mobile tower data, CCTV footage and geospatial data can inform this.

Quarantine management

This is an important part of containing the spread of the virus, by confirming that people have stayed within defined areas. Security data, cellphone data and artificial intelligence information may aid in this.

Contact tracking

Another key part of containment is tracing who Covid-19 positive individuals have been in touch with, to track and treat further cases. This can be done with the help not only of health data but real time data and app tracking using Bluetooth.

Impact and interdependency

To manage health outcomes, authorities also want to understand where the vulnerabilities are and what factors may aggravate the situation. For this, statistics on vulnerabilities can assist.

Socioeconomic data ecosystem

Pandemic response and recovery measures

For businesses and organisations to operate as well as possible through the pandemic, continuation plans based on data can be a lifesaver. Private sector statistics can help inform this.

Fiscal stimulus

To stabilise the economy and create jobs, monetary and fiscal policy initiatives can help inform the best processes.

Psycho-social impact on the vulnerable

It is important to identify marginalised and vulnerable people in society and understand the pandemic’s impact on them better. Domestic violence and child abuse data, as well as elderly citizen mapping can indentify women, children, informal workers, the elderly and poor populations in need.

Poverty and inequality

Poverty mapping data is a great help to understand the volatility in society, including food shortages and the risk of social disorder.

Education sector

The pandemic is affecting the social and behavioural development of about 13-million children in South Africa, the vast majority of whom are schooled in the public sector. Digital technology penetration data, school readiness statistics, and information about those who are unconnected helps inform this.

Impact and interdependency

To understand the greater social and economic impact and the historical trends about this, scientists can monitor statistics related to this impact.

What the NDPO has learned about Covid-19

With so much data at their fingertips, the National Policy Data Observatory (NPDO) staff have learned a lot about the Covid-19 pandemic. Here are a few of their findings as of 3 December:

The fourth wave of infections has clearly hit Gauteng, and the seven-day rolling average Covid-19 cases of this wave are higher than previous waves at this point.

The fourth wave has started from a low base, in comparison to previous waves.

The Omicron variant has at this time not had as much of an effect on the number of Covid-19 deaths, which is a good sign, possibly linked to the vaccination efforts.

Movement of people has been significantly high in the last months, especially during lower Covid-19 alert levels.

As Covid-19 cases climbed recently, so have the vaccination numbers.

By the end of this year, around 50% of eligible people in South Africa are projected to be vaccinated.

The forecast is that 70% vaccine coverage of people above 12 years old is likely to be achieved by the beginning of May 2022 if the current performance rate continues.

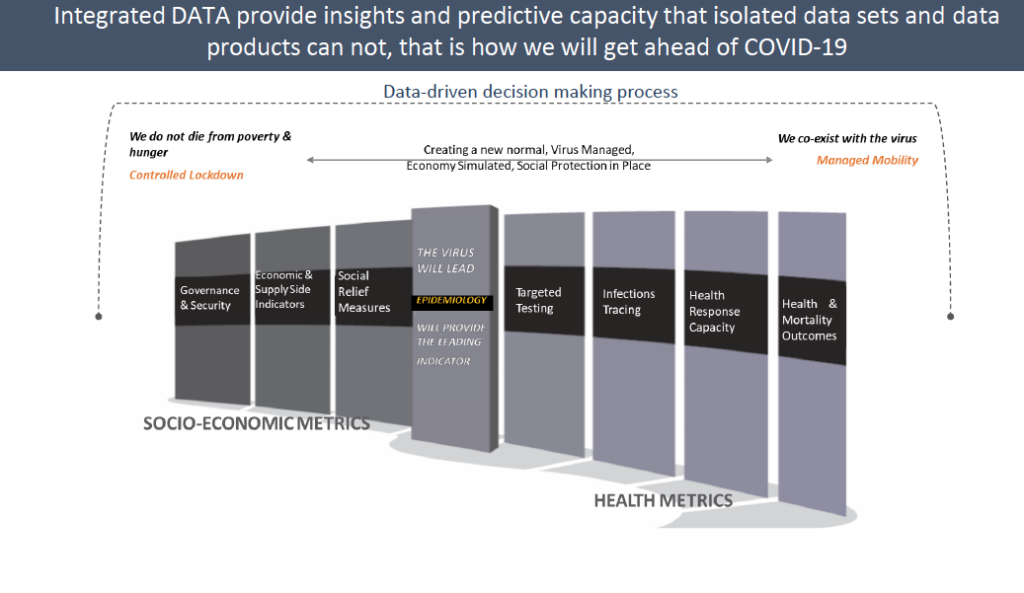

Different data, one purpose

The National Policy Data Observatory (NPDO) takes a lot of different types of statistics into consideration and examines them as a whole. Here are some of the kinds of data that might be considered together to drive decisions that allow for managed mobility and a scenario where we co-exist with the virus.

Socioeconomic metrics:

Governance and security

Economic and supply side indicators

Social relief measures

Key indicator:

Epidemiology

Health metrics:

Targeted testing

Infections tracing

Health response capacity

Health and mortality outcomes

Social science data key to changing behaviours

The Covid-19 pandemic has given researchers many things to study, and new socio-behavioural data can be the starting point for developing positive behavioural change in the future.

Professor Priscilla Reddy, a visiting scholar at the Centre for Critical Research on Race and Identity at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), explained how the recent years have demanded multiple and difficult adjustments for most people.

“What we all know from our personal lives and generally, is that behavior change at best is very difficult, but what Covid-19 needed was multiple behavior changes,” she said. “And this was wrapped in fear, mistrust, loss, grief, loss of freedom, and very importantly, as we’ve repeatedly heard, severe economic hardship for many of our colleagues.”

Reddy explains that socio-behavioural research during the pandemic was fundamentally grounded in the idea that communities are at the heart of any disease outbreak and therefore the response. How and where people live, work, play, pray, and travel; all inform this.

The key way of using this research information practically, is to start by identifying a problem and looking at the behaviours related to it. Researchers must then identify determinants that may be shaping these behaviours. Interventions should be based on this, and implemented in an ongoing process of planning and intervention.

She gave the example of the problem of low vaccine coverage and high Covid-19 cases, which is linked to behaviours of seeking and accepting vaccines.

Typical contributing factors would be knowledge and attitudes about vaccines, socioeconomic status and social and cultural or religious norms. Added to this are various demographics such as age, gender and the type of community people live in, as well as more complex factors such as prejudices, disadvantages and poverty.

“Without a detailed understanding of all these determinants, we’re not going to develop interventions that make a difference,” Reddy said.

In this example, interventions would need to be developed and adapted in such a way that they address the factors influencing risky health behaviours. This process can be tailored to a specific risk being focused on. Ultimately, scientists need to assess the success or failure of the programmes based on data for effective change.

What research tells us about vaccine hesitancy

A portion of South Africans are hesitant to get Covid-19 vaccines, and innovative research helps paint a clearer picture of why, and how to shift the needle.

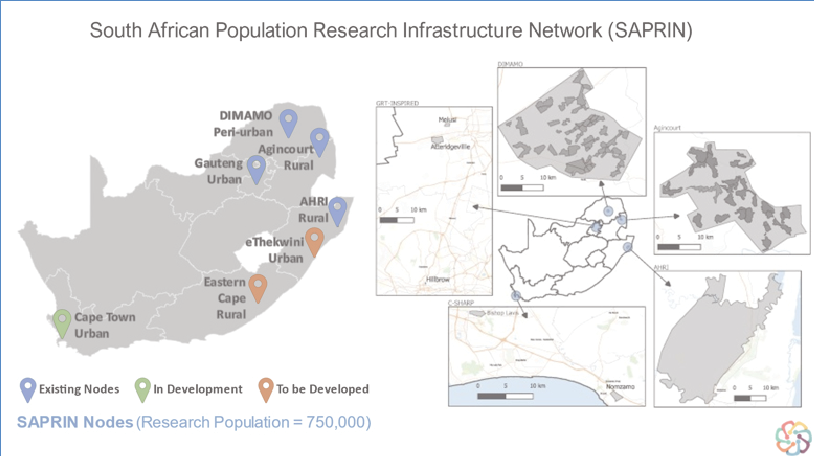

One strong source of such data is the South African Population Research Infrastructure Network (SAPRIN), which is a project funded by the Department of Science and Innovation, and hosted by the South African Medical Research Council in partnership with various universities in the country.

Whether you live in an urban or rural area, your age, education and class; these are all factors that may affect your willingness to get the Covid-19 vaccine

Whether you live in an urban or rural area, your age, education and class; these are all factors that may affect your willingness to get the Covid-19 vaccine

SAPRIN’s data currently comes from four research nodes around the country, with a total research population of about 750 000 South Africans. Three rural nodes have been in place for around 20 years; there is one node in development in Cape Town and two are planned in the Eastern Cape and eThekwini.

SAPRIN’s research follows thousands of people over long periods of time, contacting them about three times a year to note various information, including births, deaths, bio-measures and genomics. Health service, educational, and social support records are linked to this data.

The Co-Director of SAPRIN, Professor Mark Collinson, said that this powerful research infrastructure allowed for a rapid response in terms of investigating the Covid-19 pandemic. The survey started in April 2020 and is conducted on 20 000 households in the rural nodes every three months.

“Why this is important is that it’s one of the few opportunities to look at this epidemic in the population context,” he said. It also allows both for community effectiveness studies and longer-term evaluations of health outcomes.

The survey has looked into people’s vaccine history, vaccine willingness and possible reasons for vaccine hesitancy over parts of the last year. Over 50% of the population that is over 60 years old is vaccinated, but this is less in younger people.

In terms of the willingness to vaccinate, of the 75% of those surveyed who are not yet vaccinated, about 40% said they definitely would get the jab, while 20% probably would. The rest — about 15% of people — said they probably or definitely would not vaccinate. Collinson did however say that the percentage of the most vaccine-hesitant people appears to be shrinking slightly.

Research by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) backs this up, showing that overall vaccine acceptance has slightly increased over the course of the last year. About 72% of respondents are accepting.

Dr Benjamin Roberts, Research Director for Developmental, Capable and Ethical State at the HSRC, said this is ”fairly positive news, as indeed it is an upward tendency, but it does fall short of the government’s target of vaccinating 80% of adults”.

Importantly, there seems to be a substantial gap between those who are accepting or intend to get vaccinated and the actual rates of vaccinating. Understanding hesitancy and access barriers better can help possibly overcome these barriers.

Roberts added that their research also showed that certain age, race and class or spatial groups were more likely to be vaccine hesitant, such as white adults, those in suburbs, those with higher education levels, and the under-35 age group.

However, this becomes less clear-cut when political support and other measures are taken into account. For instance, how people believed that government leadership and other authority figures handled the pandemic affected their willingness to vaccinate. Whether they were willing to make sacrifices for the common good also had an effect. Men were less likely to get a vaccine.

The SAPRIN survey also asked people to describe why they were hesitant to receive the vaccine. Interestingly, not giving or having a reason is quite common. Some of the most popular answers were that they were scared of needles, worried about the side effects, or think that the jab will not work, which seems to have increased with time.

Others spoke of being allergic to the vaccines, not getting vaccines in general, being scared they may get Covid-19 from the vaccines or not being concerned about the illness. A small number of people said that they were worried that the jab would be expensive, or that the process of getting the vaccine would take too long, or be too inconvenient. Others decided not to get the vaccine because they had already been infected.

The HSRC study found that the main reason why people were acceptant of the vaccine was because they believed they were protecting themselves and society.

Regardless of other demographics, the HSRC research also found that side effects and how effective the vaccine is were key reasons for hesitancy.

“The explanations for vaccine hesitancy related to social media and conspiracy theories, and religious objections were only held by a very small minority of cases,” Roberts said.

Collinson said: “There are avenues for changing minds, because many of the points that are raised are not actually fact-based.”

Roberts said that knowledge about vaccines is crucial in terms of promoting acceptance. This information still comes through the conventional media mainly, but social media is also important, especially for younger groups. The main focus of changing attitudes should be the “moveable middle” of people who are still somewhat unconvinced of the vaccine, but may still change their minds.

Professor Shane Norris, the director of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, said that they have found that those who rely more on family and friends to receive information about Covid-19 rather than government sources were four times more likely to not to take the vaccine.

Collinson said that the vaccine rollout in the surveyed communities is making progress, with an apparent trajectory towards about 80% vaccination uptake eventually, if those who are willing are able to access it, which he believes they will.

How to move the needle on poverty and inequality

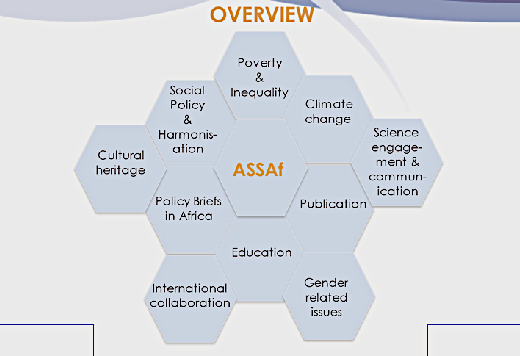

The Academy of Science of South Africa’s (ASSAf) held a number of webinars over the course of the pandemic that gave birth to insights concerning poverty alleviation and inequality.

Researchers looking at how to actively reduce poverty and inequality recommended cash transfers as the most viable option for poverty alleviation in the short term. Professor Himla Soodyall, Executive Officer of ASSAf, said: “Cash transfers directly reduce hunger and improve [the] wellbeing of recipients, with the Child Support Grant and the Old Age Pension being the most targeted.”

How to alleviate poverty was among the topics discussed at a number of recent ASSAf webinars

How to alleviate poverty was among the topics discussed at a number of recent ASSAf webinarsPublic employment programmes such as the Expanded Public Works Programme do have an impact on people’s wellbeing, but this is unfortunately not extended beyond the time of the project and are therefore short-lived.

Funding interventions to reduce poverty is the next hurdle. Soodyall said that the key message from their work on this is that proposed taxes will generate more revenue, but that this will not cover a comprehensive cash transfer programme.

This is because the country has limited fiscal space available, which comes out of poor economic performance and governance. “Nonetheless, the state cannot hide behind this constraint, as large poverty alleviation programmes are needed,” Soodyall said.

So, to make the state capable of shifting the needle on this, there has to be a fundamental rethink of the regulatory environment, so that innovation and rapid responses can be encouraged that will alleviate poverty.

Scientists suggest that the government must put measures in place to improve its own capacity, improve resources and align itself with the objectives of a nation in a developmental process.

Child malnutrition during pandemic is slow violence, say researchers

As more data comes to light about how the pandemic has affected the country beyond health impacts, it’s clear that children have been affected significantly, particularly in terms of food security.

Professor Julian May, Director of the Centre of Excellence in Food Security at the University of the Western Cape, called the state of child malnutrition a slow violence “because here we are talking about changes which are often not observed, but which are damaging over a lifecycle and which are damaging to a society”.

Professor Julian May, Director of the Centre of Excellence in Food Security at the University of the Western Cape

Professor Julian May, Director of the Centre of Excellence in Food Security at the University of the Western Cape

Childhood stunting for those under five years old has persisted since the 1990s. “Ultimately, child stunting is essentially flatlined,” May said. “We’ve made no progress.” This is the case despite the significant increase of the Child Support Grant reaching millions of children since 1998, and South Africa adopting similar strategies to countries that have had declines in child malnutrition, such as Brazil.

Trends in terms of undernourishment, hunger, adult obesity and anemia in women all declined over recent decades, and then dipped up fairly significantly since the pandemic. May said: “So that, then, is our concern. We have the largest social protection system in Africa, but we continue to have a high prevalence of stunting.”

The pandemic has impacted children and their access to food in a myriad of practical ways. This included the closure of schools and Early Childhood Development programmes, and a rise of about 14% in food prices towards the end of 2020.

Rising unemployment, restrictions on informal sector street hawkers, and the withdrawal of caregiver and top-up grants has had a direct effect on children. Disruption to routine health services and increased hesitancy to access primary health care is also linked.

The Centre of Excellence in Human Development has done a cohort study of women in Soweto, which revealed worrying results that may feed into child malnutrition. Director Shane Norris said: “One alarming area of data that’s emerging from the work we’re doing is the impact of Covid-19, directly and indirectly, around women’s access to maternal child health services.”

Women are generally going to antenatal clinics later and less often than usual, despite these services being well-used in urban areas before the pandemic. There is also a hesitancy to visit Baby Wellness Clinics. About 10% of the pregnant women in the study terminated their pregnancies; reasons directly or indirectly linked to the pandemic were frequently given during the counselling process.

“And this is an important part, to understand that the pervasiveness of the pandemic is going to have a multiple rate of effect on behavior and consequences of those changes in behaviors.”

This is all in the context of how paradoxical the food system in the country is. On the one hand, South Africa has a positive food balance and the capacity to import, sophisticated science and innovation programmes as well as advanced food policy. However, there is still an overall poor nutrition record, with under- and overnutrition continuing as well as persistent food insecurity.

May said that what can be learned is that “the bottom line of our message is to put children at the heart of the food system”. Interventions to this may include a focus on making healthy food available, affordable, acceptable, desirable and sustainable by focusing action across humanitarian relief, job and social protection, the agri-food industry, retail, and schools.

Data shows labour and employment fluctuations throughout pandemic

The largest non-medical study currently in South Africa, The National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), has provided an interesting look into the economic and social implications of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Professor Reza Daniels, from the school of economics at the University of Cape Town, said surveys showed that employment levels bounced back a bit every time the country went back to Covid-19 Alert Level 1.This trend was not reflected in other labour force statistics, such as from StatsSA, but that’s mostly down to differences in how they were designed.

Government regulations such as lockdowns affected employment greatly during the pandemic, creating effects such as ‘employment churning’

Government regulations such as lockdowns affected employment greatly during the pandemic, creating effects such as ‘employment churning’

Daniels added that there was also a percentage of people who were furloughed, meaning that they stayed in employment relationships but were not fully paid as usual.

“Now, the importance of this is really to show that government regulations with respect to how we handle the pandemic do matter. They matter greatly.”

The Director of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, Shane Norris, said that qualitative studies during the 2020 lockdowns also showed that families from lower income households were more likely to report retrenchments, pay cuts, or losses of temporary jobs.

The socioeconomic impact of the pandemic can also be seen in the data concerning grants. Women were initially not getting the level of grants that men were, despite accounting for most of the Covid-19 related job losses. This was then corrected, after some time.

Another trend is what Daniels calls “employment churning” where people go in and out of employment repeatedly. “This is showing that people are getting piecemeal or piece-rate jobs. Often these were associated with service industries growing, such as in the actual mobile delivery of goods.” These adjustments in the economy helped affect employment levels to some degree.

Sadly, the pandemic also affected the levels of hunger in the country. About 1.8-million people, and 400 000 children, are considered to have perpetual hunger, meaning that they are hungry almost every day. Daniels said this was the highest rate seen since the 1990s, and that it was likely created by the temporary closing of school feeding schemes and the likes during the pandemic.

This trend also had negative consequences in terms of mental health. Research shows that about 40% of adults living with children in food-insecure households showed signs of depressive moods in April 2021. A year earlier, this was closer to 26%.

“That, again, was something that was showing us a very new picture about the sociology and anthropology of this disease and the impact to it,” Daniels said.

Communicating the pandemic

The Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand has supported a variety of projects during the Covid-19 pandemic, with some interesting results.

The Centre’s Think Tank brought together behaviour change specialists around the country. They researched how countries around the world reacted to the pandemic, and noticed some significant movements in behaviour change action plans.

The researchers noted that only the United Kingdom, the United States, the European Union, Australia and New Zealand had such extensive plans in place. India, which is notable on the list for being a lower-income country, went a step further to create a Covid-19 communication plan and put it into place.

The Centre’s Director, Professor Shane Norris, noted: “It’s clear that communication is pivotal in a national response to a pandemic and in some ways, we’ve done very well, and in other ways less so.”

Norris said that the so-called “family meetings” with President Cyril Ramaphosa have shown to be effective, reassuring, credible, and are a decisive display of leadership.

The work the Centre’s communication experts have done has revealed that mixed messaging is a problem and a stumbling block. Norris said there have been cases where misinformation or mixed messaging, including internationally, seem to have influenced South Africans’ opinions strongly. He explained that myths must be attempted to be countered quickly as they can affect greater issues of public concern, such as vaccine uptake.

Scientific evidence matters: South Africa must be a continental leader

Professor Rémi Quirion

Chief Scientist of Quebec

President, International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA)

Sir Peter Gluckman

President, International Science Council (ISC)

Former Chief Science Adviser to the Prime Minister of New Zealand

During both our careers, we have had the privilege of teaching students, advising Prime Ministers and making friends for life within the pillars of the global science establishment. We wear many hats, from addressing domestic and international challenges around how science feeds-in to policy-making that impacts the daily lives of every man, woman and child, to helping steer the large, union-style membership organisations that act as the voice of researchers across the world. Examples include vaccination and immunisations, tackling pollution in our cities and advising on legal and illicit drug use.

These “life and death” issues have resonance for countries worldwide. Yet, our day-to-day interactions were always flanked by awareness of progress in other countries and among those were valuable relationships with the South African science system. Indeed, the International Network for Government Science Advice’s (INGSA) first training school was held in South Africa. As a leader in pan-African policy innovation, South Africa gets the importance of scientific evidence to support laws meeting the nation and its citizens’ needs. That said, we have always questioned why the voice of African scientists is not nearly heard enough by policymakers inside Africa, as in most places in the world. This must change.

Professor Rémi Quirion, Chief Scientist of Quebec and President, International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA)

Professor Rémi Quirion, Chief Scientist of Quebec and President, International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA)

We have shared multiple platforms with South African leaders and intellectuals. Usually, this is in Europe or America. The creation of Science Forum South Africa (www.sfsa.co.za/) has been a real game-changer and eye-opener for so many. Now, we can come to you! This week’s 7th edition has not been dampened at all by the pandemic, with over 2 500 pre-registrations. It is a remarkable feat by Minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology Blade Nzimande and his team. In fact, the hybrid panels with free, open access on the internet are democratising science like never before. We have all been impressed by the carrier-wave effect SFSA has had in igniting conversations about science, society, education, youth, innovation and diplomacy across Africa.

South Africa is leading the way in promoting the critical importance of education and scientific literacy for all. Seeing African Union Ambassadors, EU officials, the talking heads of your Academies of Science, National Advisory Councils and hundreds of youth representatives, in particular, all jockeying for seats at the Council for Science and Industrial Research’s convention center in Pretoria is something truly magical to behold.

South African scientists are in global demand too. Dr Shamila Nair-Bedouelle’s appointment as Assistant Director-General for the Natural Sciences at UNESCO or Dr Albert van Jaarsveld’s appointment as Director General and CEO of the Vienna-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, are just two of many examples. I (Sir Peter Gluckman) have also recently replaced former President of the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf), Professor Daya Reddy, as President of the Paris-based International Science Council. We are delighted to have Professor Salim Abdool Karim as one of our Vice-Presidents (of the International Science Council) and Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor as a member of our new Global Commission for Science Missions on Sustainability. Karim is such a world-famous epidemiologist, the embodiment of a science for social justice scientist, flying the South African flag with devotion and humility. Cape Town’s hosting of World Science Forum 2022 and other internationally recognised gatherings showcase how South Africa’s scientific reputation is on the rise.

If Covid-19 is the 9/11 moment for global science advice, what needs to happen next?

We, and the tens of thousands of members we represent, are strong believers in the value of independent science advice in complex decision making. These are issues where scientific evidence and public or political values do not necessarily align. For those who believe wholeheartedly in evidence and the integrity of science, the past two years have been challenging. Information, correct and incorrect, can spread like a virus. We are certainly at a turning point, not just in this pandemic, but in our collective management of longer-term challenges affecting us all.

That is why our key international panel discussion held at Science Forum South Africa on Thursday 2 December is so timely (also free to view post-event). Moderated by Professor Himla Soodyall, CEO of the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf), this high-level panel brings together politicians, chief science advisors, presidents of science advisory bodies and science diplomats from five continents to examine how scientific advice feeds into effective policymaking, or not. Our premise is that if the 9/11 attacks changed all our lives from the perspective of state security, then Covid-19 must leave a similar legacy for the future of globally robust policymaking as a shared public good. Or must we be prepared to accept the dumbing-down of “evidence” and a “snapback to normal” in our post-pandemic politics?

We argue that the importance of open science and access to data has never been more critical and we spell out what is really at stake in the relationship between science and policymaking, both during crises and within our daily lives. From the air we breathe, the food we eat and the cars we drive, to the medical treatments or vaccines we take, and the education we provide to children, this relationship, and the decisions it can influence, matter immensely. It is much more than a philosophical debate.

To begin, the panel unpicks how science and politics share common features. Both operate at the boundaries of knowledge and uncertainty, but approach problems differently. Scientists constantly question and challenge our assumptions, searching for empiric evidence to determine the best options. In contrast, politicians are most often guided by the (short-term) needs or demands of voters and by ideology. When this necessitates “not needing experts” or “we are following expert advice” mantras the lines may become blurred. The panel argues that this pandemic has brought to the fore a third force. What is changing is that most grass-roots citizens are no longer ill-informed and passive bystanders. They want to have their voices heard and are rightfully demanding greater transparency and accountability. This brings the complex contradictions between evidence and ideology into the public eye like never before.

On the upside, rapid scientific advances in managing the pandemic are generating enormous public interest in evidence-based decision making. Practically every country has a new, much-followed advisory body. Many scientists have become public celebrities too. That said, does this carrier-wave for citizen engagement with science and the tremendous opportunities to advance the status of science and research funding (trillions of rands being poured in), not risk being derailed by the real threat of science and scientists being viewed as a political force? What does the playbook of science advisory systems teach us?

In addition, speakers representing diverse continental views examine the pandemic’s legacy as not just a disease, but as an exemplifier of humanity’s inhumanities and interdependencies. From vaccine equity and the starkly highlighted fault-lines between rich and poor countries, the strength of international co-operation continues to be tested. (President Cyril Ramaphosa’s comments about the Omicron variant flight bans into South Africa leaves nothing to the imagination on that subject). What is, however, clear is that societies worldwide both profess intolerance for “inequality”, while providing and even sometimes cherishing the legal and social settings that legitimises it. From last year’s blanket ban on alcohol and tobacco sales during lockdown in South Africa to today’s anti-vaccination riots across Europe or North America, the panel tackles thorny questions concerning how civil liberties, taxation, jobs, sectoral interests and culture all come into play.

Looking forward, we also try to map-out what reformed or new regional or global facilities and institutions might be needed, where and why? Should we defenders and loyal gatekeepers of the scientific status quo put our hands up and lead the charge to “out” the most gross failures in our global advisory systems? Is the World Health Organization up for root and branch reform? What role do we science brokers play in reshaping the world of work, utterly transformed by digital technologies and artificial intelligence? Is the “profession” of evidence-based policymaking itself in the riflescope?

Sir Peter Gluckman, President, International Science Council (ISC), Former Chief Science Adviser to the Prime Minister of New Zealand

Sir Peter Gluckman, President, International Science Council (ISC), Former Chief Science Adviser to the Prime Minister of New Zealand

Our collective aim in supporting SFSA is to weigh-up how lawmakers must navigate between the rights and responsibilities of individuals to look after themselves and the rights and responsibilities of states to look after their citizens, provide security and a milieu in which to live a satisfying life. Further issues accentuated by the pandemic we debated with strong inputs of Professor Derrick Swartz, Special Adviser to Nzimande, include concepts of democracy and the rule of law, the influence of religious views and the pressing need for the acceptance of global public goods to be universally applied. While aiming to uncover points of agreement and potential disagreement in equal measure, the panel’s shared goal is to help build and elevate open an ongoing public and policy dialogue about the role of robust evidence in sound policymaking.

Will South Africa embrace its scientific reputation rise to the benefit of the continent?

With about 50 ministers, 11official languages and a dizzying array of public, private and civil society influencers, it’s easy to see how South Africa’s elected representatives have particularly challenging roles. Policymaking is ultimately about choices between options that involve different tradeoffs affecting different stakeholders in different ways. It is entirely proper that in choosing between possible options, policymakers weigh up societal and political values — fiscal, diplomatic, ideological and religious, to name but a few — and they will always have an imminent electoral risk in mind. But science has a critical role in providing the understandings that will underpin those policy choices.

People’s worldviews are too often reinforced by the information bubbles they now live in, which means that many only listen to people and media whose views align with their own inherent biases and ideologies. People want categorical answers. Science can rarely provide them. And social media and other non-neutral media can be effectively used to manipulate opinion, often by claiming “facts” and “truths” even when they are neither facts nor truths. Such manipulation not only undermines democracy, but also undermines society’s ability to use knowledge to make progress. There is always a danger that even the best available science can be ignored in such an environment. When that happens, it is more likely that policy outcomes will not serve the citizen well.

But, as expectations on policy processes grow, science and robust evidence have increasingly essential roles to play. Science has multiple disciplines defined by a set of processes designed to find as-reliable-as-possible knowledge about the world within and beyond us. When used to inform the policymaker and the citizen, science can identify what options really exist and what are the likely consequences of each. Of course, science is always provisional, but that should not be an excuse for ignoring it. Nor should it be dismissed simply because it does not fit with prior biases or fixed views. But science can reduce the heat in values-laden debates that can otherwise be drowned in polemical rhetoric and assist decision-makers to work through complex and seemingly irresolvable issues.

One of the most difficult areas of public policy is, for example, harm reduction science, aimed at reducing the adverse health, social and economic consequences of the use of legal and illegal psychoactive drugs. What we often see is that the science will be cherry-picked or interpreted to advance opposing arguments whether you are on the side of the “war on drugs” and “quit or die” or support “greater empathy for addicted persons”. Civil society and industry actors are well drilled in this. In turn, this can reinforce firm convictions about the validity or otherwise of the science.

For example, the harm from smoking tobacco is well understood. Fifty percent of smokers may die from related diseases. South Africa is losing 42 000 citizens a year. It is universally accepted that smoking kills. The science is still evolving when it comes to products such as vapes, heated tobacco and nicotine pouches, hence the difficult policy debates worldwide. These alternatives to smoking clearly reduce exposure to cancer-causing chemicals and any reduction in carcinogen exposure is clearly beneficial to current smokers. On the other hand, some argue that it may create a gateway to smoking. The long-term safety of these new products is unclear. The variety of emerging options for smokers creates further uncertainties. Regulation is needed. Policy dilemmas are apparent that only truly independent science can resolve. We need African research and African voices inputting on these decisions.

Another example is the importance of vaccinations and immunisations. Yet the “anti-vax” movement seems impossible to eradicate — it is supported by false science, rejected by every robust health authority and scientific academy, and yet is promoted by celebrities and other non-experts. There are side effects to vaccination, but the societal sense of precaution and risk assessment has balanced those risks as being small in relation to the consequences of pandemic illnesses vaccination is designed to eradicate. But for the policymakers having to weigh up such decisions, scientific support and evaluation is essential.

Our fundamental belief is that science alone cannot decide on such matters. “Evidence” is one among many types of advice that inform the decision-making process. Above all, the meaning of risk varies. Risk to a politician is very different to that of a citizen. Key determinants such as information selection, confirmation bias, polarisation etcetera require greater understanding and attention. Others include ethical values, cultures, politics and the impact any decision can have on other areas of policy. How to balance risk and precaution is a recurrent theme for politicians and the leaders of their national science systems. That said, the scientific community must stand behind its evidence and shout out when policymakers clearly get it wrong.

The interaction between science, societal values, concepts of risk and precaution and politics pervade every aspect of a democratic society. Whether it is dealing with climate change, artificial intelligence or tackling Covid-19, in every case both the natural and social sciences working together have an important role to play. Better decisions are more likely when science is properly used. We as Presidents of the International Network for Government Science Advice and the International Science Council will never be moved from defending that. In recent years, South Africa has understood and is embracing this too. The sense of shared confidence apparent in this year’s opening panels at SFSA are infectious. The parallel reputation-rise of South African science has been impressive to see. Fifty-six million South Africans and 1.2-billion Africans have a stake in this continuing.

Visit INGSA at: www.globalscienceadvice.org/

Visit ISC at: https://council.science

Locally developed and affordable Covid-19 antigen test gets the green light from SAHPRA

The desire of Cape Town-based company Medical Diagnostech for South Africans to have access to cost-effective diagnostics, as the Covid-19 pandemic persists has been realised, with the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) approving their Covid-19 antigen detection kit.

Medical Diagnostech, established in 2010, is a local developer and manufacturer of high-quality rapid diagnostic test kits. It recently received approval for its MD SARS-nCoV-2 Antigen Device.

Diagnostech Founder and CEO Ashley Uys

Diagnostech Founder and CEO Ashley Uys

The approved antigen detection device is a rapid visual immunoassay for the qualitative detection of the Covid-19 Nucleocapsid protein (N-protein) antigen from nasopharyngeal swabs. It can diagnose acute infection, providing information on whether the patient is currently infected, unlike antibody tests, which provide information on whether the patient has previously been infected and has elicited an immune response against the virus.

The company’s Founder and CEO, Ashley Uys, said access to cost-effective diagnostics is vital in the fight against Covid-19, especially in Africa. SAHPRA’s approval of the MD SARS-nCoV-2 Antigen Device provides just such a platform.

Uys added that the company is busy developing an application for smartphones to interpret results from the device, which will reduce subjectivity while creating a portal for data generation, interpretation and management, as well as statistical analysis, in compliance with the Protection of Personal Information Act.

“Medical Diagnostech has already produced initial commercial batches, and has a production capacity of 20-million units per annum, but is also in the process of scaling up,” Uys said, adding that all test kits were produced in Cape Town.

This latest approval by SAHPRA provides yet another boost to the country’s efforts in developing and scaling up local reagents and point-of-care tests for self-sufficiency in relation to SARS-CoV-2. In August, the regulator authorised the manufacture of rapid Covid-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test kits by local biotech company CapeBio.

These developments could not have come at a better time in South Africa, where a fourth wave of Covid-19 infections, and the discovery of the apparently highly infectious Omicron variant, have made widespread testing increasingly important.

In mid-2020, the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) rallied key local partners from government, academia and industry to help reduce the country’s reliance on international test kit supplies, through the local development and manufacture of robust alternatives, capable of producing results before patients leave the testing site.

With the guidance of the National Health Laboratory Service and others, the SAMRC, together with Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and the Technology Innovation Agency (TIA), a DSI entity, jointly ran a call for applications to identify suitable projects for funding.

Following the peer review, selection and approval processes, Medical Diagnostech, along with two other local companies and a science council, received funding to develop rapid point-of-care tests for Covid-19.

Three of these, including Medical Diagnostech, were aimed at direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigens within 15 to 30 minutes. Medical Diagnostech had already developed a prototype antigen detection test, and required support to increase its sensitivity and complete the testing and approvals for market entry.

Welcoming the latest announcement, Dr Michelle Mulder, Executive Director for Grants Innovation and Product Development at the SAMRC, said: “This investment from the SAMRC, DSI and TIA has enabled the final product development steps required to deliver an approved antigen detection test for Covid-19 that meets the minimum globally accepted performance criteria for such tests.

“The local ownership and manufacture of these test kits will not only increase South Africa’s self-sufficiency in a time of high demand, but also contribute to reducing the trade imbalance with respect to medical devices and local economic development and job creation.”

Dr Phil Mjwara, Director-General at the DSI, said the latest development further expanded South Africa’s ability to respond to Covid-19.

“Not only has the DSI supported the development of a capability to locally produce the reagents for PCR tests by start-up company CapeBio, but the Department, together with the SAMRC, believed that with the necessary funding it was possible to locally develop rapid tests for the detection of active Covid-19.”

The Director-General said this vision and investment had paid off with Medical Diagnostech’s Covid-19 antigen test, which lowers the cost of testing active infections. “This technology not only benefits the country, but will also be made available to the rest of Africa,” Mjwara added.

The head of TIA’s health programme, Osmond Muroyiwa, said the organisation was living by its mantra that innovation must answer to the challenges of the day. “We are living in a moment where science has to provide answers in tracking an invisible enemy that has ravaged societies and economies globally.

“The ability to produce test kits locally is testimony to the great scientists and innovators we have, who, with the right support, can help save lives, reduce imports, create jobs, and ultimately improve the quality of life of all South Africans,” Muroyiwa concluded.

Research lessons to be learned from the Covid era

While the Covid-19 pandemic has been unfolding, a number of local research projects have been underway, doing the work to understand how this era is affecting the country and its people. The inputs from the social sciences and humanities give insights not only into what has happened, but what can be done going forward.

Professor Sarah Mosoetsa, CEO of the National Institute for the Humanities and the Social Sciences (NIHSS) and an associate professor at the University of Witwatersrand, calls this period of time the “Covid decade”.

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen serious clashes between people, the environment and technology says Professor Sarah Mosoetsa. (Photo: Emmanuel Croset /AFP)

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen serious clashes between people, the environment and technology says Professor Sarah Mosoetsa. (Photo: Emmanuel Croset /AFP)

“It has led to a number of devastations and tragedies at different levels including the social, psychological, political, and most importantly, at an economic level.” Mosoetsa said that in the time we have found ourselves in, there have been serious clashes between people, the environment and technology, but that it does not have to remain this way.

She said that research done by herself, the NIHSS and various universities shows that it is possible to turn this clash into coexistence between people and their context.

“First, what we know from research is that there are long-term implications around structural inequalities that we need to grapple with,” Mosaetsa said. A research project by teams at the universities of the Witwatersrand and Cape Town titled Rethinking Economic Policy for South Africa in the age of Covid-19 has explored how this can be addressed.

The researchers conclude that the pandemic crisis can be used as a springboard by the government to reconsider the nation’s heavy reliance on wage labour as a revenue generation tool. Instead, there should be a rethinking and an emphasis on social security.

Another long-term impact is that of pupils who have dropped out of school during or because of the pandemic. This needs to be addressed, given the long-term effects it could have for the country. As Mosaetsa said: “We have always thought about education as a potential for resolving our poverty and inequality crisis.”

While many South Africans have been affected by the pandemic, these long-haul effects are not distributed equally. Mosaetsa said: “Covid-19 has had a different impact based on your locality, your gender, but most importantly, your class location.”

Another insight to be gleaned from this era is that history often repeats itself and South Africa and academia should learn from this time. “What we don’t want is that when there is another crisis or another pandemic, that it finds us unplanned, unco-ordinated, and not working together, because indeed, that will be a big fuss.”

A plan with a longer-term view

While the last few years have set the stage for how the social and natural sciences can co-operate, it is absolutely essential that they do so in the future.

One plan that may lead the way is the Science and Technology Innovation Decadal Plan for 2021-2031, which is currently in the process of being finalised.

Dr Phil Mjwara, Director-General, Department of Science and Innovation, gave a sneak peak into this during a recent ministerial plenary session during the 2021 edition of Science Forum South Africa (SFSA).

Dr Phil Mjwara, Director-General, Department of Science and Innovation

Dr Phil Mjwara, Director-General, Department of Science and Innovation

Mjwara said that one of the priorities in the Decadal Plan is addressing climate change. He said that while there is a clear role here for natural scientists to play, in terms of understanding the warming planet, the humanities are also crucial.

The social sciences are able to contribute a more nuanced understanding of what climate change is, and what a “just transition” means for people on the street and the issues that affect them, such as job creation and food security.

“We would need the interface between natural scientists and social scientists to work together to provide the country with what this ‘just transition’ means,” he said.

The Decadal plan will also focus on the future of society, which will require a similar type of co-operation. Mjwara said that the work of groups such as the The National Policy Data Observatory (NPDO) and researchers in the humanities will be particularly important here.

“Societies globally are undergoing major changes as a result of new technologies, but it’s the interface between those new technologies and society that require that we think of how science, the humanities and data are going to drive the future of society.”

In a June 2021 briefing to a Parliamentary Committee, Mjwara revealed that further themes of the plan include a circular economy, nutrition, food security and water security. Health innovation as well as education are on the list, as is sustainable energy. The plan includes a focus on high-tech industrialisation as well as ICTs and Smart Systems.

The plan is intended to be integrated with ongoing programmes already in place. There will be an effort in looking at how the plan can affect important areas beyond the key topics, such as tourism, the provision of infrastructure, local and rural development, as well as government decision making.

Mjwara explained that the plan was progressing towards finalisation and that Cabinet had approved the direction of the draft plan so that it can be further discussed with relevant stakeholders such as those in business, academia and civil society.

He views the future with hope, and looks forward to seeing how different disciplines will work together. “My request to the humanities and social sciences is that, please, get ready to work with the natural scientists.” He joked: “I am a natural scientist; don’t be scared, we are very easy people to work with!”