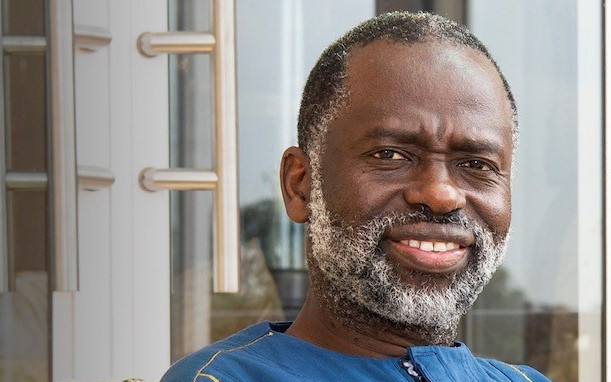

Jansie Niehaus, Executive Director at the National Science and Technology Forum

At the recent discussion forum hosted by the National Science and Technology Forum (NSTF), the civil society science, engineering and technology (SET) stakeholders’ body focused on the creative economy, science and the fourth industrial revolution (4IR). The forum brought together stakeholders from the SET community to consider cross-cutting questions on creativity, science, technology and the economy. The goal was to examine the interface between the creative industries and science and technology, to discover the overlaps between them, and to unpack how these can be translated into innovation and the growth of the economy.

“Innovation as technological innovation has economic implications, which applies to the creative economy too,” said Jansie Niehaus, Executive Director at NSTF. “Innovation generates income, starts businesses, and transforms economic potential. Today we are also at a crossroads, with new technologies that offer artists new ways of creating, marketing and protecting art works. These are themes that are worth exploring to drive creative and technological growth in the era of the fourth industrial revolution.”

Guest speaker Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg (UJ) and author of Closing the Gap, a book about the 4IR in Africa, gave a talk on how 4IR can affect lives and how it is primarily associated with artificial intelligence (AI). He clarified the tenets of the 4IR and its implications for innovation across both creativity and technology.

Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of University of Johannesburg

Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of University of Johannesburg

“One of his most important points is that if we don’t have data, we can’t make AI work for us. AI needs massive amounts of data to be useful and to draw valid conclusions from the data,” said Niehaus. “Africa in general tends to lag behind in the collection of data and databases that AI can use. We therefore tend to lose out on being represented in global data and fail to benefit from economic and technological developments. We need to set up our own systems for collecting data and generating the skills to manage data and to use AI to make innovation possible.”

Dr Tegan Bristow, Senior Lecturer and Director: Fak’ugesi Festival, Wits University; James McCarthy, Director: McCarthy Legal; and Sipho Dikweni, Commercialisation Manager: Technology Innovation Agency (TIA), set the tone for the first day of the forum. They unpacked the contribution of technological innovation in creative economies; the role of non-fungible tokens (NFT) in managing intellectual property; and how the Fak’ugesi Festival plays a role in bringing together the two worlds of digital and creativity into an innovative whole.

Artist Mbongeni Buthelezi

Artist Mbongeni Buthelezi

“There is a real exploration of how creative work can be generated on a digital basis, and how the evolution of innovation and creativity can be supported,” said Niehaus. “This is truly essential for South Africa’s growth, and something that Dr Audrey Verhaeghe, CEO: South African Innovation Summit (SAIS), unpacked in her keynote on the second day. She emphasised the importance of bringing together technology start-ups and funders on a platform where they can create synergies for the future.”

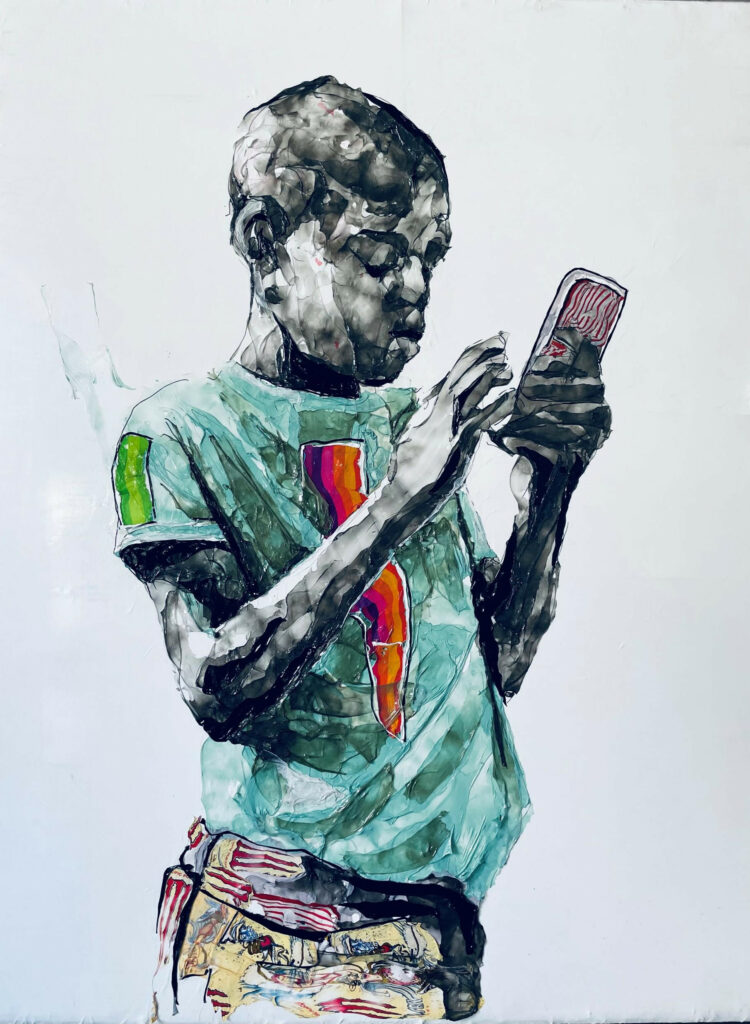

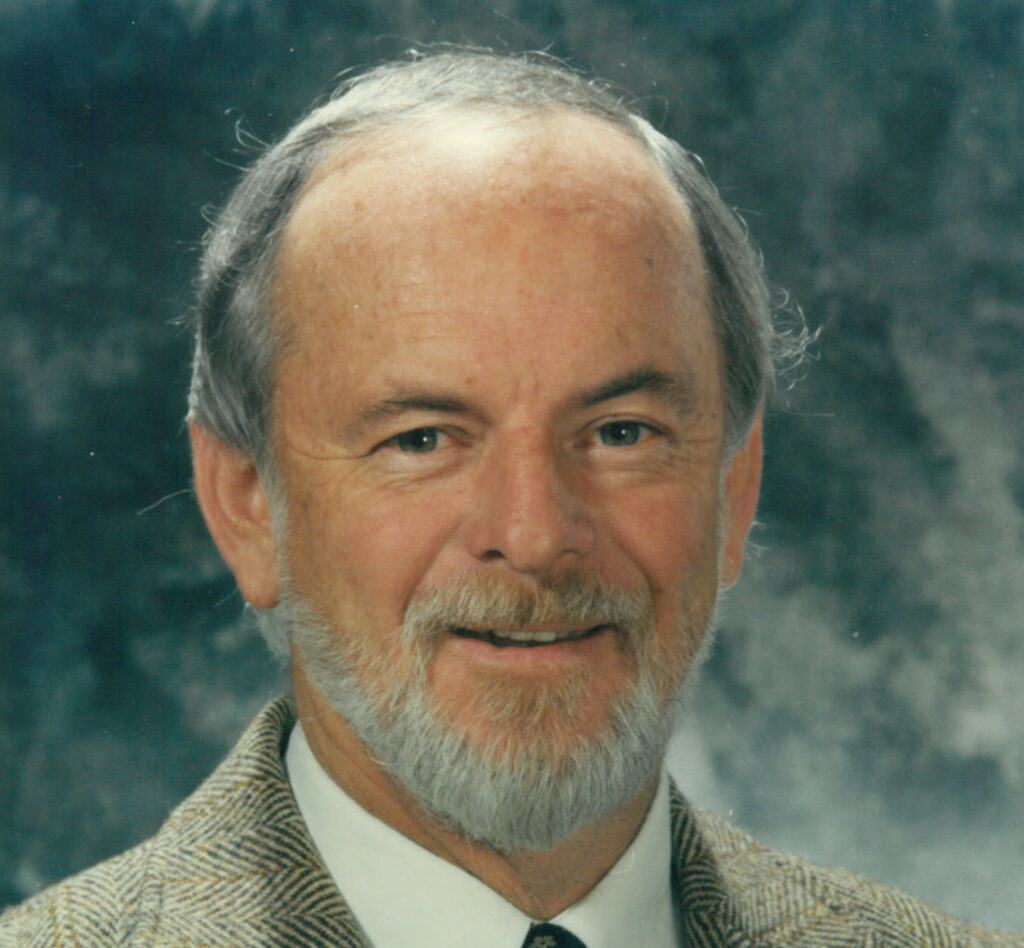

Within the powerful presentations on the day that unpacked AI, NFTs, blockchain, connectivity and technological innovation, there were two that reflected the immense value of the skills of creativity: Mbongeni Buthelezi, an artist who uses waste plastic to create his art, and Professor Mike Bruton, author of What a Great Idea and winner of the 2002 NSTF Lifetime Award. Buthelezi creates extraordinary works of art using waste plastic bags and a heat gun.

“Buthelezi creates intuitively and his work is an example of how artists can innovate because they think outside the box,” said Niehaus. “Professor Bruton has just written a book on innovations in Africa called Harambee, which is now available from bookshops. He shines much-needed and inspiring light on skills, creativity and the spirit of African ingenuity.”

An art work by Buthelezi, made with waste plastic

An art work by Buthelezi, made with waste plastic

Bruton’s insights were inspirational for several reasons; he highlighted the fact that South Africans are responsible for more than 700 inventions, such as the first machine used to drill tunnels for the first underground railways in England, for Oil of Olay, and for the Lodox low-dose X-ray machine, among many others. He also eloquently pointed out that the potential of the 4IR cannot lie in semantics, but requires that there’s a major change of mindset so that South Africa can take advantage of it. This is where civil society can truly make a powerful impact on the creative economy, by pioneering new trends to democratise technology.

“There’s massive participation through connectivity and technology that has resulted in problem resolution being carried out by a multi-generational superorganism, a collective of human genius, that can collaborate to create solutions,” concluded Burton. “Perhaps the best example being a CERN paper with more than 5 000 co-authors of the next generation of globally connected and digitally competent creative and scientific minds. And Africa has a very strong role to play in this regard.”

— Tamsin Oxford

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Creative endeavour in the era of 4IR

The creative economy is important. It shapes a future that’s empowering and inspiring, that enables employment opportunities, generates income, and can make significant contributions to achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Creative industry is the expression of imagination, community, society, culture, feelings, social messages and values. South Africa has remarkable gifts of creativity and excellent artists. We also have diverse and engaging voices that can articulate developments in the technology, creative and innovative spaces, sometimes in unusual and interesting ways.

At a recent event hosted by the National Science and Technology Forum (NSTF) entitled Creative Economy, Science and the 4IR, some of South Africa’s leading voices unpacked related matters and what this could mean for the future.

Dr Tegan Bristow, Principal Researcher and Senior Lecturer at Wits and Director of the Fak’ugesi Festival

Dr Tegan Bristow, Principal Researcher and Senior Lecturer at Wits and Director of the Fak’ugesi Festival

The most prominent voice was that of the guest speaker, Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg (UJ), author of Closing the Gap (among more than 40 books) and a past NSTF award winner. He is renowned as a thought leader on the 4IR in South Africa and Africa and is a cultivator of future high-end skills related to the 4IR. Another speaker, who set the scene for the two days, was the current winner of the NSTF-South32 Special Annual Theme Award, Dr Tegan Bristow of Wits University. Professor Mike Bruton, known for his extensive ichthyology work and popular science writing, and also a winner of an NSTF Award, sketched an important perspective on the issues that were discussed. For him, the key to unlocking the potential of the creative economy lies in multi-disciplinary educational experiences that allow for people to recognise the potential of the 4IR (or first post-industrial revolution, as he prefers to call it).

“4IR is about the merging of technology and humanity to create a connected ecosystem,” he explained. “Most of us can’t live without our devices and we can see a world where we are becoming a single system that’s transforming communication and education. It’s more than just technology-driven change; it’s leaders and policymakers and people from all income groups harnessing technologies to create an inclusive, human-centred future.”

Marwala believes that there is a skillset involved in re-imagining modern life, that some people use to find intriguing solutions to problems using technology. Isaac Asimov captured this perfectly in his essay on creativity: “Presumably, the process of creativity, whatever it is, is essentially the same in all its branches and varieties, so that the evolution of a new art form, a new gadget, a new scientific principle, all involve common factors.” This is echoed by economist Joseph Schumpeter, who came up with the term “creative destruction” to define the incessant innovation of product and process that impacts both macroeconomic performance and economic fluctuations.

“Schumpeter said it is a form of industrial mutation that revolutionises the economic structure from within, destroying the old while creating the new,” said Marwala. “The reality is that innovations in products and services can increase our gross domestic product (GDP), and Africa isn’t innovating in the same way as the United States or China or other countries. We can astound the world with our creativity, with our innovation.”

Professor Mike Bruton, ‘imagineer’, researcher and author

Professor Mike Bruton, ‘imagineer’, researcher and author

This is a view shared by Sipho Dikweni, Commercialisation Manager: Technology Innovation Agency (TIA), who pointed out that meaningful contributions to the creative economy, especially in the digital world, require a shift in thinking so that the continent can take part in the dramatically different world that is now emerging from the influence of the 4IR.

“We can see new forms of art and management tools, new business models and stakeholder relations, and the rise of virtual communities with digital assets and art,” he said. “There are augmented and virtual realities where humans can become immersed in the meta-verse, and where we can showcase our creative solutions without physical engagement. This means that creators have to rethink their strategies so that they can continue to contribute to, and compete within, this new world.”

As Bristow, Fak’ugesi Director, and Principal Researcher and Senior Lecturer at the Wits School of the Arts, with a specialisation on African Art, Culture and Technology, pointed out, the intersection between art and science is a very interesting location.

“Often, it’s about translation and perception and understanding what happens in the artistic process from a scientific perspective,” she said. “These conversations have to go both ways in order for them to be valuable and well considered. In part, this is what informs Fak’ugesi, a festival that’s focused on digital art and digital innovation within unusual projects that showcase the talent that defines Africa.”

Bristow highlighted how Africa is a powerful melting pot of innovation, creative thinking and scientific invention that has become a meeting place for content creators, technologists and enthusiasts that are all committed to a revival in Africa. This, too, is how Fak’ugesi operates: as a springboard for people to network, to see how creative people can be, and how technology plays a pivotal role in igniting this creativity and innovation.

“We use this to open up opportunities for interdisciplinary, inter-institutional collaboration that’s so important in this emerging culture,” said Bristow. “Creativity in the past was seen from the perspective of painting, drawing, theatre, music and poetry, but now we need to focus on digital creativity, immersive media, and the intersections of creativity and technology. Already people’s perceptions are changing — if you’d said ‘digital art’ to someone in 2014 they would have asked you why. Today they would ask completely different questions.”

This is certainly how Marwala believes the world is changing. The Africa of today can transform to achieve so much more, thanks to inventive approaches and smart thinking. But this requires a commitment from heads of state and governments across Africa, one that shows support for this growth and this creative economy and provides the regulatory and legal support that people need to thrive.

“In South Africa, we have a 4IR strategy that looks good and talks about real things that must happen in our economy,” said Marwala. “It recommends that we invest into human capacity development and get education back to where it is supposed to be. None of these 4IR strategies are going to work unless we have adequate human capacity that’s equal to the task, that ensures people understand the human side of education, the social side and the technological side.”

Sipho Dikweni, Commercialisation Manager, Technology Innovation Agency

Sipho Dikweni, Commercialisation Manager, Technology Innovation Agency

“Whatever form of art we create to expand our audience will increase our market share, our revenues and our social security,” Dikweni added. “But all this cannot happen if we don’t have technology and solutions like blockchain to secure art work originality and maintain authenticity. We need technologies that ensure artists transact with the right people, and connectivity that brings it all together. We need to prepare South Africans for the future so our creators can participate on the global stage and redefine our creative economy.”

Bristow agreed, pointing out that there is sometimes very little understanding of how the cultural and creative industries engage with 4IR technologies. Few people understand the technology, which is perhaps why it has not been given as much attention as it needs to truly thrive. Every creative innovation can potentially shape the next industrial revolution.

“In the first industrial revolution there were steam-powered engines and many people don’t know that the textile weaving industry, mostly in Europe and the United Kingdom, contributed significantly to the concept of automation,” said Bristow. “We wouldn’t necessarily have computers today if people weren’t weaving beautiful textiles in the past, which makes it important to think about how culture and creative industries influence technology as well.”

The future is not just interacting with other technologies, but what happens when technology interacts with humans and societies. The people who create this technology need to understand this complex ecosystem and its impact, taking the conversation full circle back to the importance of multidisciplinary education experiences. Creativity requires an open mind, an education system that encourages enquiry, and an understanding of the environment in which people live.

As Marwala concluded: “It is important to enrich the lives of all people, whether they are young or old, and to use technology to refine experiences, enhance diversity and empower people.” — Tamsin Oxford

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The implications of AI for human creativity

Artificial Intelligence (AI) no longer belongs to the realm of sci-fi and isn’t something only a few philosophers and computer scientists are thinking about. It’s here, to the extent that we now accept machine learning and automation as normal and are discussing what new developments in AI capabilities could mean. Of course, AI still has its sceptics, and they’re not only those generally anxious about technology. The late Stephen Hawking called AI the “worst event in the history of our civilization” and Elon Musk declared it a “fundamental risk to the existence of human civilization”. Others point more optimistically to it enabling human creativity.

Professor Deshen Moodley, co-director of South African National Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research (CAIR) and Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science, UCT

Professor Deshen Moodley, co-director of South African National Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research (CAIR) and Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science, UCT

The question of the impact of AI on human creativity was the substance of a presentation by Professor Deshen Moodley as part of the National Science and Technology Forum’s March discussion forum on the Creative Economy, Science and the 4IR. Moodley is the co-director and co-founder of the South African National Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research (CAIR) and Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Cape Town (UCT). The NSTF is a stakeholder forum for organisations whose mandate is related to science, engineering, technology (SET), and is a consultative forum for influencing the formulation and delivery of public policy in South Africa.

To understand the question of the impact of AI on human creativity, we need to examine the terms “human”, “AI”, and “creativity”, at least in this context. Moodley does not see AI as a technology or a solution: “It should be viewed more as an enabling technology for digitalisation, so it typically sits within a digital system or a robot; it is not in and of itself an independent technology, it’s part of the digitalisation endeavour.

“AI-enabled computers today learn from experience, and can adapt to changing situations and surpass humans in specific tasks, such as complex calculations. They can also perform creative tasks such as creating new art and music. This learning and adapting ability, together with rapid fusion, analysis and communication of vast amounts of information in real-time over local and global networks is at the core of AI,” he said. Autonomous intelligence (of the kind Hawking and Musk warn against) involves autonomous machines, such as self-driving vehicles.

What makes us human is a permanent philosophical question, but the key quality that Moodley focused on is emotional intelligence. Think of empathy: the ability of humans to not only care about others, but to actually experience their emotions, to understand them deeply because they are shared. Interfaces that incorporate notions of empathy are becoming available, but critics point out that gathering data to mimic empathy is not quite the same as empathy itself, nor is data-informed mimicry of creativity enough to meet creative criteria.

This is a view shared by Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg (UJ), who spoke of how this is the time to harness the potential of innovative thinking, adapting to our current context with solutions that move at the pace of social and technological change. He said: “South Africa has to have a stake in AI technology, which is why we need to focus on the implementation of this important technology in all areas of our lives, whether it’s the economy or society. It is the engine of 4IR and we need to enable it right now.”

As Moodley asked: “To what extent can AI and machines create new art and music, and to what extent can AI do creative tasks?” In the same way that AI can gather data to mimic human emotions like empathy, it’s clear that AI can be creative, if creativity is seen as a skill that can be learned from data. When that learning results in a work that arouses feelings in viewers and listeners, it’s not hard to see it as creative. The news is full of stories of AI creating original art, poetry and paintings. IBM’s Watson, for example, produced an AI-generated sci-fi movie trailer, ads for Toyota and original cooking recipes. AI-generated digital artwork has been sold for huge sums.

It’s the higher-order levels of creativity where the debate lies. Human creativity, some point out, involves intentionality, valuation and emotion. The result is something novel and unexpected. Humans use random data to make new things that no one else has done before. AI can’t do that, but it can augment human creativity, quickly providing data that humans can work with by providing rough drafts and concepts for us to work with. Nobody knows if future AI capabilities will achieve higher-order creativity.

For Moodley, the future of the human-AI relationship lies in collaboration. “What we really want to do is leverage the strength of both human and machine, where machines work in tandem with humans and humans in tandem with machines. AI must learn and adapt to the human user as humans learn and adapt to AI.” This kind of AI, he believes, needs an interdisciplinary approach, and should not be left up to computer scientists alone. — Elaine Williams

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Technology is set to transform IP protection: Here’s how

The notion of intellectual property (IP) is a global one that has taken many interesting twists and turns through the generations, even more so in a technology-driven world. In a space where indigenous knowledge systems and creations made purely by artificial intelligence co-exist, it’s worth exploring just how intellectual property is protected, and how it can be monetised for the benefits of its owners.

Dr Audrey Verhaeghe, founder of the South African Innovation Summit

Dr Audrey Verhaeghe, founder of the South African Innovation Summit

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) says that the rationale for adopting and protecting IP is to give statutory expression to the rights of creators and innovators in their creations and innovations, balanced against the public interest in accessing those creations and innovations. It is also to promote creativity and innovation, which in turn contribute to social and economic development.

African tech startups’ IP journey

Dr Audrey Verhaeghe is the outgoing CEO and founder of the South African Innovation Summit, co-founder of the Research Institute for Innovation and Sustainability (RIIS) and more recently, ANZA Capital. She said that the Summit’s intention was always to find and accelerate technology start-ups by showcasing them to potential investors, connecting them with mentors, and capaciting them for growth.

“There’s a $42-trillion gap in Africa’s early funding landscape, whether it’s for funding to get a garage-grown idea to market or to bring a university-incubated concept to fruition,” she said. “There’s so much potential for new products and services that respond directly to the global sustainable development goals, not least because 20% of the world’s population lives on the continent, and 60% of that population is under 25.”

The successful commercialisation of tech companies founders’ IP depends on a number of shifts, including start-ups working on market readiness as much as they work on technology readiness, and working on investment readiness as much as investor readiness. It’s also essential to recognise that technology start-ups are different from small businesses, and need to be treated and protected differently.

Using tech to protect IP

If creators are working in a digital world, one way that they could protect their intellectual property is by creating non-fungible tokens (NFTs) for their work, whether that work is artistic or more utilitarian.

James McCarthy, entertainment law specialist at McCarthy Legal

James McCarthy, entertainment law specialist at McCarthy Legal

That’s according to James McCarthy, an entertainment and creative law specialist, who explained that NFTs are traceable tokens that are traded and recorded on a digital ledger or blockchain. These tokens hold uncompromisable data about who created the item, meaning that they are trustworthy beyond reproach, along with the item’s price, who traded it, and when they did so.

“NFTs allow for increased tradability,” he explained. “For example, a New York diamond dealer has created NFTs for each of its stones, that each hold the gem’s unique information. This makes it possible for each stone to be sold as many as hundreds of times a day, without incurring the costs of moving it around securely. Buyers trust the data in the NFT, and don’t need to see the stone first hand — and they’re confident that holding the NFT attached to a particular stone reflects genuine ownership of the item.”

NFTs attached to art works offer the same simplicity and reassurance, along with additional earning opportunities. “Minting an NFT includes drafting a smart contract that governs how that NFT can be traded, and that contract could include a clause that the artist gets a cut of secondary sales,” McCarthy said. “This means that, potentially for the first time in history, artists can earn revenue in perpetuity from one piece of original artwork, as well as from licensed reproductions of that work.”

Protecting indigenous knowledge in the tech world

With 71% of South Africans believing that we put too much trust in science and not enough in indigenous knowledge, and, according to the World Health Organisation, that 80% of the world’s population uses traditional medicine for primary healthcare, it is plausible that this knowledge could and should be used as an income source for traditional healers.

But where does ownership of that intellectual property vest? Tecla Spiller, a law student with degrees in African Archaeology, Classical Civilisations and English Literature, pointed out that defining how much of that knowledge is secret and sacred is not just a legal dilemma, but a cultural one too.

“The tension exists because intellectual property rights are typically around the rights of an individual, whereas cultural knowledge is intellectual, and so much of it has been passed down through oral traditions over generations,” Spiller said. “It is also intergenerational, rather than just pertaining to one lifetime.”

South Africa has set the standard for protecting indigenous property rights through the Protection, Promotion, Development, and Management of Indigenous Knowledge Act 6 of 2019, which is used alongside the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act. The Act protects all forms of indigenous knowledge, including how it is used for economic, moral and customary benefit. — Kerry Haggard