Split-second loss: Italy’s Lamont Marcell Jacobs (right) crosses the finish line to win ahead of the US’s Fred Kerley (left), who came second, while Akani Simbine ended fourth in the men’s 100m final during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games.

(Jewel Samad/AFP)

Last weekend’s 100m sprint at the Tokyo Olympic Games is painful to rewatch through a South African lens. Akani Simbine had shot off the blocks in lane two but soon found himself trailing behind Fred Kerley while the tall-standing, muscular figure of Lamont Marcell Jacobs surged past him to his immediate right. He would have still won bronze had it not been for the spindly Canadian Andre de Grasse who, in the fashion typical of a 200m enthusiast, powered on as most of the field began to slow down in the final metres.

Simbine was left to contemplate a brutal reality of sprinting at this level: that four-hundredths of a second is all it takes to be denied a spot on the podium and that a dream can be lost in the abyss of an almost immeasurable gap.

The three men in front of him had also run the best race of their lives. Had he matched his own personal best he would have finished in at least third. But statistics are just that, of course.

As the sting of disappointment begins to soften however, both Simbine and his team will begin to run forward again – towards a future that still appears bright.

We shouldn’t forget, after all, that history was made on the Tokyo track. Simbine, Gift Leotlela and Shaun Maswanganyi represented the first time that three South Africans had made the semifinal. All of them carried a posture of genuine expectation. All will, hopefully, maintain belief in their abilities.

“It sucks. For me, I just wanted to be on the podium. It’s been five years of just missing out and now it’s another year and another year to miss out on a podium,” Simbine told the gathered media after the event.

“It’s going to drive me even more, to train even harder and next year be a faster and a better athlete. I still believe in two more Olympics, that’s my goal. I’m not going to stop after this because I’m disappointed. I’m going to go on, I believe I can win a gold medal, it’ll happen whenever my time is.”

His mission will take place in the most unpredictable era the sport has seen in at least two decades. In the lead-up to this year’s sprints, the inevitable talking point was who would succeed Usain Bolt. The Jamaican had enjoyed such a dominant career that even in retirement his spectre received more attention than any of the athletes on track.

But no one could predict just how volatile the void he left behind would be.

It began in the semifinals. Trayvon Bromell, the fastest man this year, couldn’t even get through, while the less renowned Su Bingtian visibly stretched every sinew in his body to become the second Asian man in history – and first since 1932 – to make the final (incredibly his 9.83s was the second-best across the Games and would have been good enough for silver had he replicated it).

And then there was the final itself. Few fancied US-born Jacobs to bring gold to Italy but none could deny the level of his performance. Unlike his predecessor Bolt, there was no pre-pistol showboating or extravagance. No cheeky glance to his right as he trotted over the line. Only pure effort and unnerving determination; pounding the floor with every step from metre 1 to 100.

This is once more an event in which anybody can have his day. Simbine is right to think his may well still come.

Even more so, arguably, are Leotlela and Maswanganyi. The pair, 23 and 20 years old, respectively, have every reason to believe that with consistency and the right training they can improve on their already impressive times. National 200m record holder Clarence Munyai, who is also 23, may well hold a similar hope.

In his 2015 analysis, academic Roger Pielke Jr found that on average, the fastest male athletes that the 100m race has seen put in their best performance during their mid-20s. That conclusion seems to have been vindicated last weekend as the top three all ran personal bests and happen to each be 26 years old.

In other words, the in-form years for the young South Africans may well be still ahead.

Of course, that’s not a forgone conclusion, either for Munyai, Leotlela and Maswanganyi or for Simbine, who will be 28 in September. He instead may well take encouragement from the aforementioned Su.

The Chinese speedster just set his best time, an Asian record, at 31. Having gradually improved his results over the last few seasons, he credits a switch-up in technique to his performances. With his time stuck at above 10s, he followed the advice of experts to switch up his stance and put his left foot on the forward block instead of the right. It was like relearning to use a fork again with a different hand but has undoubtedly paid dividends now.

There is unlikely to be a tweak so blatant for the South Africans but the point remains: sprinting is an imperfect science melded to passion and hard work. We have seen enough to take encouragement from this year’s track.

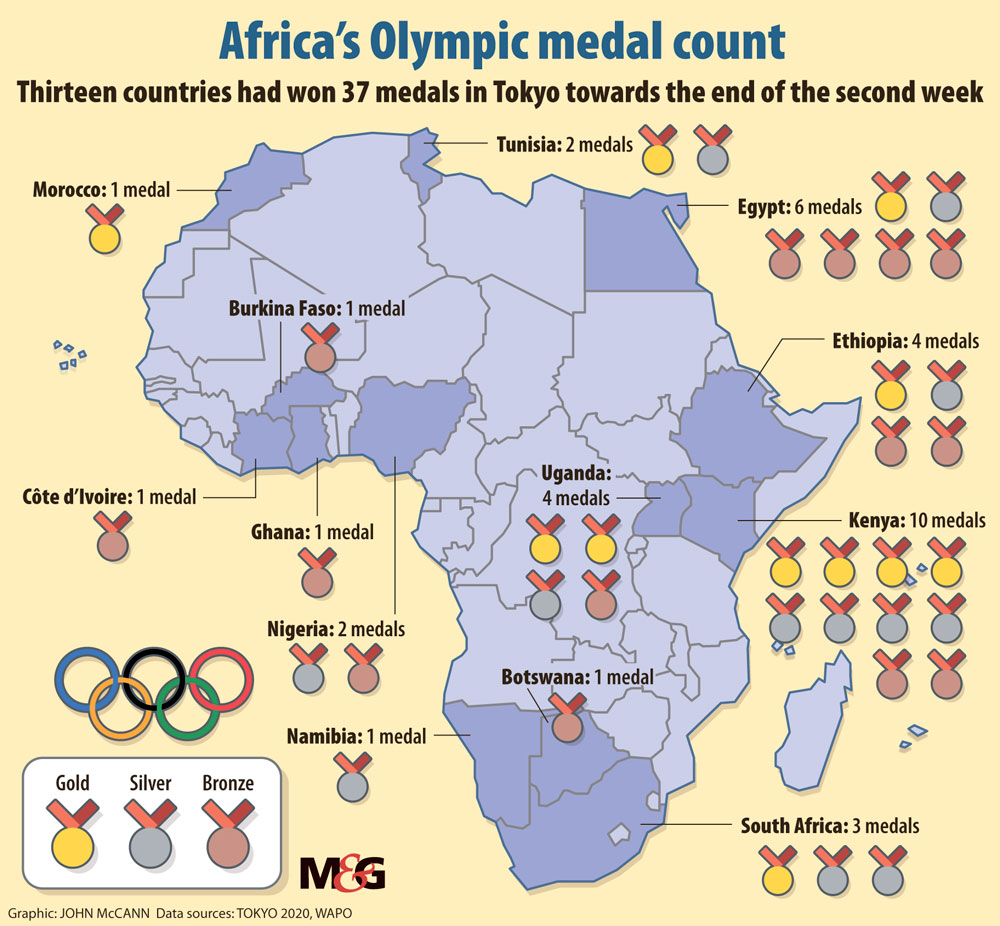

Admittedly, it’s a very different silver lining to the last Olympics. Rio brought the nation 10 medals, its greatest haul since being readmitted to the Olympics in 1992, having been expelled about two decades previously for its racially discriminatory apartheid system.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

There was a real sense that the team was building something special, particularly in athletics. Unfortunately, the two stars of Rio 2016, Wayde van Niekerk and Caster Semenya, have since been derailed – one by cruel bad luck and the other by cruel regulations.

This year there have only been three medals at the time of publication, two of them scooped by the exceptional Tatjana Schoenmaker in the pool and one by surfer Bianca Buitendag. None in athletics.

We can’t do much to change that now except follow the first rule of sprinting: look ahead with our heads up high.