Shane Warne during the 2nd test played between South Africa and Australia at the Newlands cricket ground, Cape Town, South Africa in March 2002. (Photo: Touchline Photo/Getty Images)

March 2002. South Africa versus Australia at Newlands. Glorious weather. And a truly remarkable Test match. Just look at the scores. As a Test match wicket should, it offered help for the strong Australian seam trio of Glenn McGrath, Jason Gillespie and Brett Lee, who share eight of the wickets as the Proteas struggle to 239 all out.

In reply, Australia are 185-6, but then Adam Gilchrist delivers one of his trademark counter-attacking innings – 138 off 108 balls. A certain Shane Warne, the great, iconoclastic leg-spinner chips in with a valuable 63 batting at eight. 382 all out, and a lead of 143. Then, remarkably, South Africa fought long and hard to reach 473, setting Australia 330 to win – which remains the record for a fourth innings chase at Newlands, finished off with a dismissive slog sweep by Australian captain Rickie Ponting, that I nearly caught as I sat in my customary seat in the Railway Stand.

The previous two days, I had taken the opportunity of a thinning-out, late-in-the-day crowd to move behind the bowler’s arm. It was Warne, who reeled off, over two days, an extraordinary 70 overs from the Wynberg end. It was truly mesmerising, prompting me to write my first and probably only congratulations note to an Australian cricketer.

70 overs, in that heat. The next highest was 29.

One, two, three, four, maybe five ambled steps towards the wicket, like a man calmly but carefully approaching a newsstand, with time to still snub out a cigarette, but with eyes set on his target twenty-two yards away. And then a quick dancer’s two-step up in his gather and his powerful shoulder propelling the ball down the track.

420 times he did so in that compelling spell, barely uninterrupted except by the overnight break in play (over 40 000 times in his fifteen-year Test career that yielded 708 wickets at an average of 25.4).

Wisden reported it thus: “Warne, slimmed down but not wholly reformed, compared his marathon to “a big night out when you think you’re gone several times, but you get a couple of second winds”.

The record for six-ball overs in a Test innings is 129, by West Indian spinner Sonny Ramadhin in 1957. In the modern era, seventy overs is almost unheard of, and was rewarded with six wickets. Warne was declared to be the man of this magnificent Test match, his 100th.

Like a Warne spell itself, this prolonged preamble “buries the lead”, which is simple yet for cricket lovers around the world truly shocking: Shane Warne has died, aged just 52.

Jonty Rhodes and Shane Warne of Australia chat after the 7th ODI between South Africa and Australia played at Newlands, Cape Town, South Africa, 2002. (Photo:Touchline Photo/Getty Images)

Jonty Rhodes and Shane Warne of Australia chat after the 7th ODI between South Africa and Australia played at Newlands, Cape Town, South Africa, 2002. (Photo:Touchline Photo/Getty Images)

In a way, it is entirely in keeping with the man; he always had a surprise up his sleeve.

But more often than not he was “slow burn”. Many of his spells were about luring a batsman into an enticing web. Most of the successful spinners are smart; they think very carefully about how they are going to prevail. They don’t have the power to intimidate that a fast bowler does – though Warne’s charisma was said to have a mesmerising capacity to strike fear into even the most confident of batters.

Instead, they have, like a chess player, to figure out a route towards reward. A few stock balls. Get the batter thinking that they’re comfortable and can read the spin. Then, a slight adjustment – of line, or length, or, most significantly for a spinner, flight and pace.

Warne had all of this. And more. He also had the full wrist-spinner’s armoury of weapons: googlies and wrong ’uns; a vicious top-spinner; and a seductive “slider”.

Yet, despite this artistry and the sharp wit and tactical acuity that lay behind it, Warne was also capable of exploding out of the starting gate. That is why his most famous ball was the first ball of his first spell in Ashes cricket, at Old Trafford in 1993.

Besides his cricketing genius — and I don’t think there is a sensible-minded cricket observer on this planet who would not immediately include Warne in his or her all-time World First XI — the other, perhaps even more obvious aspect of Warne that will cement his memory in the minds of cricket fans was his magnetic charisma and character.

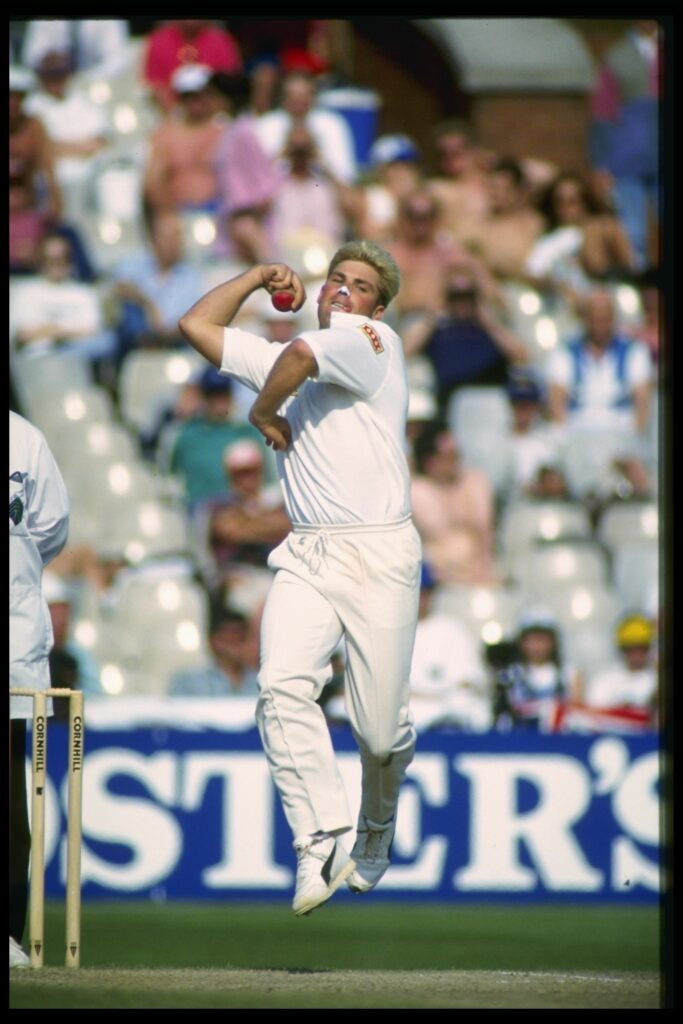

Jun 1993: Shane Warne about to bowl for Australia against England in his 1st Ashes Test at Old Trafford, Manchester (Photo:Ben Radford/Allsport UK)

Jun 1993: Shane Warne about to bowl for Australia against England in his 1st Ashes Test at Old Trafford, Manchester (Photo:Ben Radford/Allsport UK)He was never boring. There was always something interesting happening to him or around him, whether on the field or off it. To conservative purists he may well have overstepped the line at times. These are the kind of people who preferred the neatly ironed white flannels and manners of Stan Smith over Ilie Nastase in their Wimbledon duels of the 1970s. I was a Nastase man, through and through; and, hence, a “Warne man”. The Smith equivalents in cricket might have preferred Stewart McGill the relatively demure fellow leg-spinner who would probably have become a “great” had his own career not overlapped with Warne’s.

As someone once said about the liberal leader Charles Kennedy in the UK, who, like Warne, liked to smoke and drink, perhaps too much, and who also died prematurely, he “was a fully paid up member of the human race”.

Clearly, Warne had his human fallibilities and frailties — plenty of them; which made his supreme confidence with ball in hand, something every leg-spinner needs in spades if they are to master such a slippery skill, so remarkable.

It’s also why the instinctively cautious Australian cricketing establishment never gave Warne the opportunity to captain. He would have been a wondrous leader, as he proved when leading the Rajasthan Royals to the inaugural Indian Premier League titles and in the process establishing a distinctive new role for the leg-spinner as T20 match-winner.

Warne was a seriously smart cricket operator, which is why he was such an effective sledger, getting “into the heads” of many of his victims.

He brought his ebullient forthrightness, sense of mischief, and above all, cricketing brain into the commentary box. In time, he might well have become the Richie Benaud of his era – another Australian leg-spinner whose languorous style behind the microphone added further lustre to his decent record as bowler and captain of the Baggy Greens.

That enticing prospect is lost now. It’s a crying shame. But, for those of us lucky enough to have witnessed him at work, doing what he really did best, and far better than anyone before him, Warne’s imprint on the game of cricket can never be extinguished. Quite simply, he was one of the finest sportsmen in history, and certainly cricket’s greatest spin bowler.