BOTSWANA - 2019/12/14: A group of Yellow-billed storks (Mycteria ibis) in the Gomoti Plains area, a community run concession, on the edge of the Gomoti river system southeast of the Okavango Delta, Botswana. ReconAfrica has acquired rights to explore more than 35 000 square kilometres in the Okavango Delta watershed, a Unesco-designated World Heritage Site.

(Photo by Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Q7 Beckett has travelled through South Africa on foot before, but for the indigenous San youth leader, his latest 1 500km protest walk is his most important: saving the Okavango Delta, Africa’s last intact wetland wilderness, from major oil and gas development.

On 1 February, Beckett, joined by a group of San indigenous leaders and supporters, left Knysna for the Namibian consulate in Cape Town.

On Monday, they will hand over a petition from the San First People of southern Africa objecting to ReconAfrica, a Canadian oil and gas firm, to which Namibia and Botswana have given the green light to scour the Kavango Basin in the Kalahari desert for oil and gas. The petition is being sent to the Botswana government.

“As the custodians of this land for thousands of years and the rightful current inhabitants, we’ve never been consulted, nor have we given the go-ahead to any entities to prospect for oil and gas,” it reads.

Prospecting and consequent production will irrevocably damage and transform the fragile ecosystem on which the San depend.

The fight for cultural survival resonates with Beckett, whose roots can be traced to the region. “We are matriarch-led, and I grew up with all these grannies from that area, learning how to make medicine, how to heal people and play the bow instrument … Drilling for oil and gas will bring devastation to these communities.”

What’s at stake

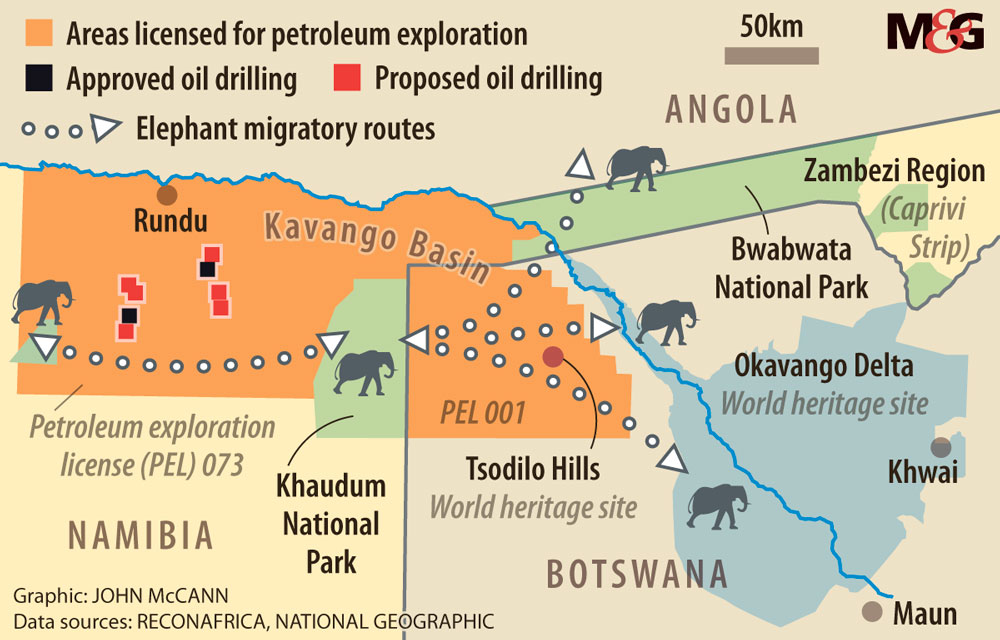

ReconAfrica has acquired rights to explore more than 35 000 square kilometres in the Okavango Delta watershed, a Unesco-designated World Heritage Site.

According to the firm’s consulting geochemist Daniel Jarvie on its website, drilling in the Kavango Basin is a no-brainer. “Given the nature of this basin and the tremendous thickness, it will be productive, and I’m expecting high-quality oil.”

Last month, ReconAfrica started exploratory drilling operations on the first of three test boreholes in Kawe, in the ephemeral Omatako riverbed in Namibia.

Opponents say the hunt for oil and gas threatens vital waterways in Namibia and the Okavango Delta’s arid savannas, home to the world’s largest elephant population and vast numbers of endangered wildlife. The exploration licence area falls within the newly-proclaimed Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier area, while the biodiversity-rich Okavango river basin is a crucial water source for over a million people.

‘No negative impacts on Okavango ecosystem’

Namibia says the proposed exploration activities “will not cause any negative impacts” to the Okavango ecosystem as they are not connected to the proposed drilling locations.

The firm’s exploration licence area originally included the Tsodilo Hills, a Unesco World Heritage Site. Unesco is following the exploration projects “with attention and concern”.

This week, Botswana’s government stated that the exploration licence does not cover the “core and buffer zones” for the “treasured” Okavango Delta and the Tsodilo Hills Heritage Sites.

Fracking fears

ReconAfrica’s marketing material refers to conventional and unconventional methods; the latter includes hydraulic fracturing or fracking, designed to recover gas and oil from shale rock. Public investor documents describe how the basin’s Permian petroleum system supports “large-scale unconventional and conventional plays”.

Frack Free Namibia & Botswana says it’s crucial to emphasise that ReconAfrica’s ultimate intention is to explore the basin to determine the presence of shale-based oil and gas. “This fact has been displayed prominently in their presentations to investors as well as in their employment of senior personnel with extensive fracking experience.”

ReconAfrica is made up of the who’s who of global fracking, says a conservationist. “These people mean business and are just getting started at the end of the fossil fuel age.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

‘We won’t be fracking.’

ReconAfrica spokesperson Claire Preece says its geological and stratigraphic testing well programme is for conventional oil. “ReconAfrica is not fracking. Conventional oil and gas production uses vertical wells, no fracking and very little water. The Kavango is a new sedimentary basin, and like all other hydrocarbon basins, conventional production is the focus.”

Both Namibia and Botswana are concerned about “misleading” information over plans to start fracking “as this does not form part of the approved programme of exploration”.

Andy Gheorghiu, of Saving Okavango’s Unique Life, says ReconAfrica will need to conduct at least one fracking operation at the end of the exploration phase to decide whether it’s worth entering the production phase.

“During the envisaged 25-year production period, the large-scale extraction of shale oil … will not be possible without the extensive use of fracking and the successive industrialisation of the licensed areas.”

He says that fracking involves massive freshwater consumption and competition with drinking water needs and irrigation; potential water contamination from fracking chemicals and the disposal of highly toxic wastewater, air pollution, a significant contribution to global warming and possible induced seismicity through the underground injection of wastewater.

‘Wrecking’ the climate

Opponents, among them David van Wyk of the Benchmarks Foundation, have sent letters to the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise. “It’s with great sadness that we see predatory Canadian corporations invading various parts of Africa, including some with the most fragile and sensitive ecosystems, to carry on activities that will harm the climate and the environment,” it reads.

Botswana and Namibia are signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement, says the San petition. “Should the Kavango basin yield the 120-billion barrels of oil equivalent predicted by Jarvie, this equates to about five billion tonnes of carbon dioxide: a climate-wrecking project.”

Together, Botswana and Namibia emit around 13-million tons of carbon annually.

Climate change impacts are much more significant for southern Africa, “compared to countries in the north that will benefit from the profits”. The San have been displaced and scattered to some of the most inhospitable, unbearably hot environments in southern Africa and “even hotter temperatures would prevent habitation”.

Water risks

Dr Surina Engelbrecht, a geohydrologist at the University of the Free State, is concerned how oil and gas exploration could affect groundwater in the shallow water tables of the Omatako river basin. Aquifers in arid areas cannot be cleaned once contaminated, she stresses.

The Okavango river basin is still relatively pristine, but oil and gas extraction could affect groundwater levels and contaminate surface water and groundwater resources, eventually reaching the Okavango Delta.

“The poor environmental impact assessment procedures that were followed and the apparent lack of a regional water resources baseline before allowing oil and gas exploration, point to a serious lack of understanding of the possible negative environmental effects … in this sensitive region.”

But Preece says the water management plan is focused on aquifer protection and management, surface water and drainage management and “project no-go buffer zones are implemented proactively”.

Project ‘will bring development’

ReconAfrica and the Namibian government say the development of a successful oil and gas industry will provide jobs, energy independence, community water wells and infrastructure.

Max Muyemburuko, the chairperson of Kavango East and West Regional Conservancy and Community Forestry Association, says locals remain “in the dark” about the project. “We depend on hunting, conservation and tourism, which are under threat.”

‘Nonsense and stupidity’

In an email, last month, ReconAfrica’s environmental assessment practitioner Dr Sindila Myiwa described concerns raised by Muyemburuko about the potential impacts of oil and gas exploration as “stupid” and “nonsense”.

Muyemburuko had “zero experience in training in oil and gas exploration” but now sought to be an “overnight expert”, he said.

Public meetings for its planned 2D seismic testing programme have been well attended, and local communities “fully support the developments being proposed in their areas”.

On 4 February, the WWF Namibia published a full-page statement in The Namibian and New Era, calling for a transboundary strategic environmental assessment before further exploratory drilling is approved.

Significant political and economic difficulties could ensue if it is discovered late in the process that there are potentially serious risks to biodiversity, water security and local communities’ welfare.