An artist's impression of the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone.

COMMENT

The flawed public participation process of the proposed mega-toxic Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ) left people in the dark about its negative livelihoods and environmental risks.

The dirty energy metallurgical cluster centres on a huge coal plant for mineral extraction and processing, of which, according to the MMSEZ’s master operational plan, 70% of what is produced is destined for China. The list of proposed industries includes a coal washery, a coking plant, a thermal plant, a ferrochrome plant, a ferromanganese plant, stainless steel, high manganese steel and vanadium steel plants as well as lime and cement plants.

The initiative — described in the final environmental impact assessment (EIA) as “the largest single planned SEZ [Special Economic Zone] in the country comprising 20 closely linked and interdependent industrial plants — will be run by a Chinese conglomerate, Shenzhen Hoi Mor Resources. Its chief executive, Yat Hoi Ning, is on the Interpol watch list after being charged with fraud by a Zimbabwean mining conglomerate, Bindura Nickel Corp and Freda Rebecca gold mine group, both listed in London.

This does not bode well for due diligence on the part of the department of trade and industry, who awarded the contract in 2017, when the charges against Yat Hoi Ning were already public, nor for accountability practices in the future, especially as there are so many oversight warning bells clanging at the start of the project. The rushed-through EIA process is a disturbing case in point.

Objections sidestepped

Between September 2020 and 31 January 2021, environmental organisations and activists hoped to stay the approval of the first high-level EIA on a variety of concerns, including the fact that Limpopo is a climate change and biodiversity hotspot. The 8 000ha site designated for the MMSEZ, situated between Musina and Makhado municipalities contains 200ha of wetlands and 150ha of baobab trees, as well as several other endemic flora and indigenous fauna.

The comments and objections of some 2 000 interested and affected parties (as listed in the final EIA) did delay the submission of the EIA by one month to allow for another round of public participation. But the 28 December level 3 lockdown again allowed a critical gap for the department of economic development, environment and tourism to insist that the EIA be finalised and submitted by 1 February.

The master plan, available on consulting company Delta BEC’s website, together with the EIA, makes it clear that the zone has a tight operational schedule. Interviews with the MMSEZ board chief executive, Leghonolo Masoga, and chairperson Rob Tooley in 2019 revealed that the Chinese operator was chomping at the bit to be operational “yesterday”.

This rush to get going is despite the fact that the MMSEZ board, the Limpopo Economic Development Agency and the department of economic development, environment and tourism know of the major flaws in the proposed project.

Aside from the Limpopo province being a climate change hotspot, it is also severely water scarce. It is a closed catchment — all available water is already designated for commercial farming, industry, mining and domestic consumption. Even now, there is not enough water to meet the socioeconomic demands, including those of vulnerable small-scale, semi-subsistence and subsistence farmers, many of whom are women.

Vague about toxic waste

The EIA, the operator’s master plan and the public presentations made by the Limpopo Economic Development Agency and Delta BEC reassure that the water crisis the MMSEZ will cause can be offset.

The demands of the coal coking, coal washing and other mineral processing industries are to be made up by water transfers from the Zhove Dam in Zimbabwe, where 80-million cubic metres of water a year are to be drawn, although no scientific evidence as to the feasibility of this supply is provided.

It’s likely the main supply of water in the early phase will come from the Thuli-Karoo aquifer, which also supplies small-scale and subsistence farmers.

Another area of concern is the EIA and the master plan are vague about the disposal of the huge amount of toxic waste that the zone will generate. The master plan suggests the ridiculous and dangerous strategy of transporting ash, slag and sludge in containers to the Holfontein hazardous waste disposal site in Ekurhuleni or the Vlakfontein hazardous waste landfill site in Vereeniging, both some six hours away in Gauteng.

Other frightening ideas are to establish a 2 000ha hazardous waste site near the zone and will be close to residential areas (see diagram).

The master plan even goes so far as to suggest it may be feasible to dump the toxic waste into the Musina and Makhado municipal landfills. This is a true horror story for local people, because coal ash contains mercury, arsenic and other toxic chemicals that can leach into groundwater, including aquifers, if not disposed of correctly.

Despite too little water and too much toxic waste, plus many other environmental concerns, the Limpopo Economic Development Agency insisted that the EIA be submitted by 1 February, declining the request of Delta BEC consultancy to allow for further public participation.

The arduous process of objecting to this first high-level EIA and subsequent EIAs is unlikely to stop the zone being established for a number of reasons.

It is already legally designated and Shenzhen Hoi Mor has an operator’s licence for the zone as of 2017.

The provincial government put out tenders for the zone in 2020.

A deal clincher is the EIA mentions the secured amount of foreign direct investment in the zone will be more than R400-billion excluding infrastructural pledges by the operator.

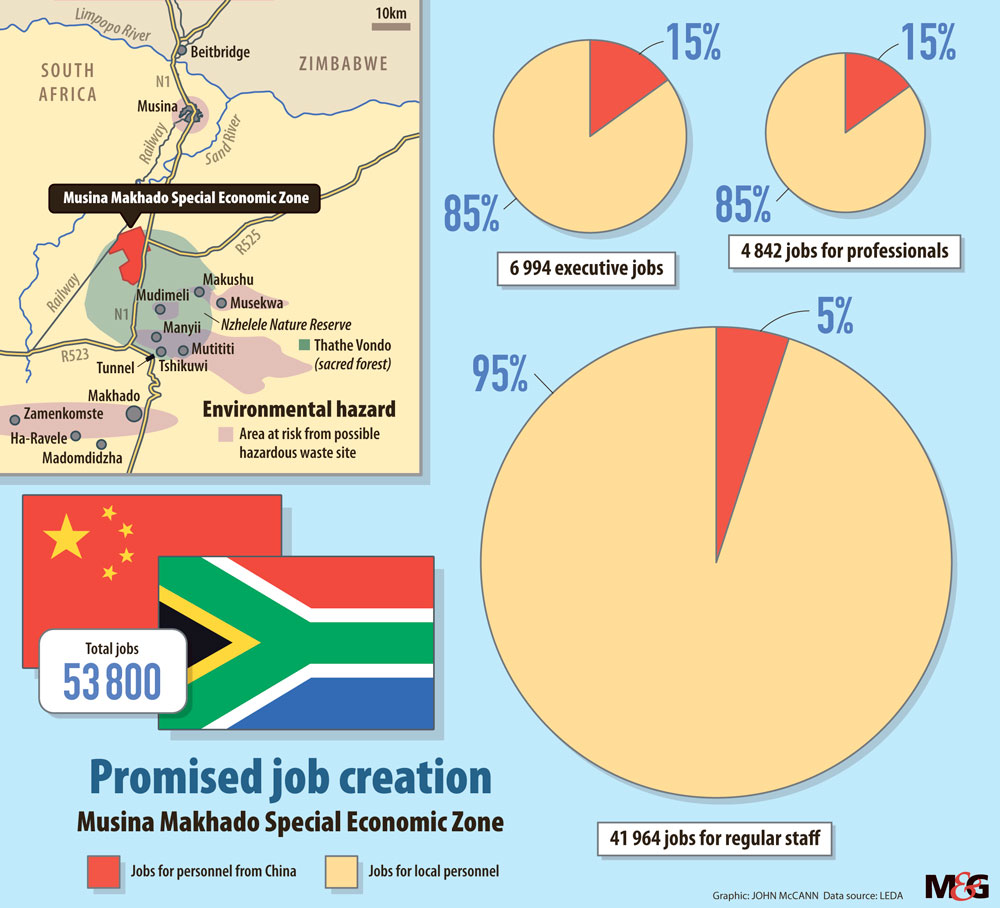

The selling point of the MMSEZ to the people who have been consulted is the promise of tens of thousands of jobs for them. Premier Stanley Mathabatha stands on record hailing “jobs, jobs, jobs…” in public announcements made on the establishment of the zone in 2019 and 2020. The final EIA makes the same point.

But last month the official number of jobs promised almost doubled. On 21 January, in an online presentation, Limpopo Economic Development Agency official Livhuwani Maligwe, when pressed on the question of jobs, estimated at about 20 000 local jobs. The final EIA promises of 53 800.

It is clear that the government will argue that employment is essential for post-Covid growth in a province rated as the second poorest in South Africa. Where exactly the executives and professionals to run the MMSEZ are to come from in Limpopo, characterised as it is by low levels of relevant educational and skills training, remains an unanswered, but critical, question.

Public pressure critical

The high-level EIA now with the Limpopo Economic Development Agency is likely to be approved. This is the first step in the government’s validation of its largest development initiative for the next two decades — carbon intensive, extractivist and destructive in the name of sustainable development.

The need for greater public awareness and of watchdogs is high: the history of Chinese megaproject investments have shown that public pressure for the disclosure of the terms of investments and loans are critical, as are conditionalities about environmental degradation control monitoring and local job creation, this without the added dodgy nature of the chief executive to run the MMSEZ (thanks to the department of trade and industry).

The battle has only just begun.