(Photo by Guiziou Franck/hemis.fr)

Namibia’s agriculture, water and land reform minister must work with other government ministries to introduce an immediate moratorium on Canadian oil and gas firm ReconAfrica’s current petroleum exploration activities in the Kavango region in Namibia.

This is the contention of Save Okavango’s Unique Life (Soul), an alliance of Namibian and Southern African civil society organisations, activists and international groups promoting social, climate and environmental justice, who have written an open letter to Minister Calle Schlettwein asking him to keep oil drilling and fracking out of the Kavango.

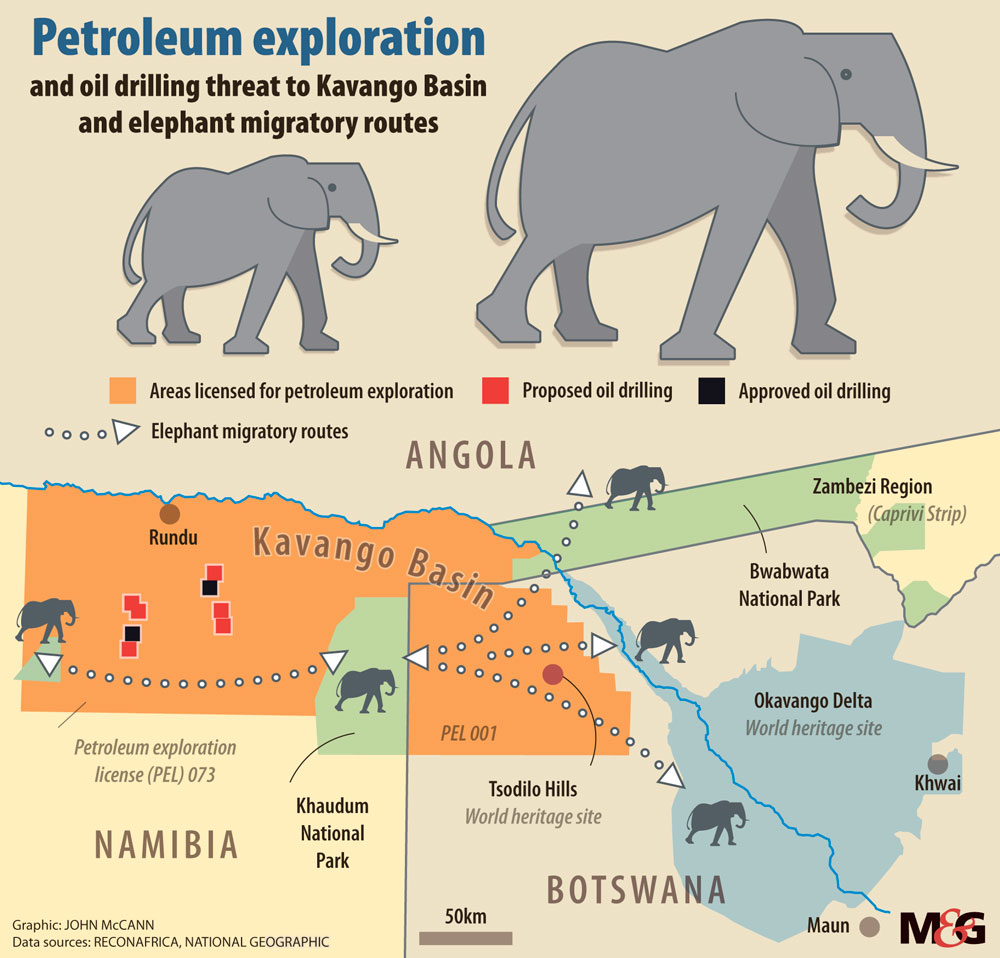

ReconAfrica has been given the go-ahead by Namibia and Botswana to explore the deep Kavango Basin in the Kalahari Desert for oil and gas. Soul said ReconAfrica hoped to find the world’s “last big oil field”.

The letter, signed by almost 80 groups, said that ReconAfrica has consistently referred to “unconventional oil and gas” in its media briefings, public information brochures and media communication.

“Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) is the technique used to extract so-called ‘unconventional’ oil and gas resources. While it has been denied that fracking will occur during the current exploration activities in the licensed area (PEL 73), it’s known that this technique must be applied to determine the extent of any shale oil or gas reservoir and the viability of extracting these hydrocarbons,” it reads.

“In the event of viable oil and gas reserves being proven, fracking will be required to release the fossil fuels from the shale formations … Without the so-called ‘stimulation drilling’, a company cannot ascertain if there is enough economically viable gas in the underground. Once companies make that positive determination, full-scale fracking will inevitably ensue.”

The company, which has acquired rights to explore more than 35 000 square kilometres in the Okavango Delta’s watershed, a Unesco-designated World Heritage Site, said earlier this month it has no plans to frack and is pursuing conventional oil and gas production alone. Both Namibia and Botswana maintain no fracking will be conducted and that environmental best practice will be followed in the exploration phase.

But Soul’s letter appeals to the Namibian government to commission a multinational transboundary strategic environmental assessment in the Kavango to investigate the cumulative temporal and spatial effects of hydraulic fracturing.

It does not make sense to “potentially contaminate groundwater resources, harm viable ecosystems and disrupt existing economic activities” in the Kavango for “foreign-owned companies to make large financial gains”, said the letter.

ReconAfrica maintains it uses an environmentally sustainable approach in all its activities. “ReconAfrica is driven to work alongside traditional, local, regional and national stakeholders to appreciate and develop opportunities for maximising development benefits from our conventional oil project.”

Soul’s letter said the 25- to 30-year period that it is anticipated the shale oil or gas extraction will last will continue to introduce carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, as well as methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Such activities “inevitably collide with the existing highly sensitive ecosystem and local communities in the targeted areas”, with negative effects that may be reflected decades or centuries after energy companies have departed.

“The very real possibility of the Namibian fiscus having to bear the clean-up and rehabilitation costs of abandoned wells must also be considered,” as demonstrated in the United States, where many shale oil and gas companies have gone into liquidation recently because of low gas prices and high operating costs.

Namibia enjoys less than half of the world average of 800mm of rainfall, with much of its water resources dependent on groundwater and, to a lesser extent, water extracted from the Kavango River.

The letter highlights a ReconAfrica research brochure issued in July 2020, which states: “Of tremendous concern in South Africa is water, a significant requirement for unconventional plays requiring fracture stimulation. Shell is looking at conservation, recycling, and brackish water as to not compete with locals for freshwater resources. ReconAfrica’s situation is significantly better in that surface rights and access are held by the government, and abundant groundwater supplies should be a source of building, not breaking, relationships with the local population.”

Soul said it is surprised by the company’s confidence to get easy access to the high amount of freshwater “required for fracking operations over the envisaged production period of at least 25 years”.

“We have the examples from the USA and saw that farmers can be particularly affected by the oil and gas industry’s demand for freshwater, especially in drought-stricken regions of the country, similar to our region”, said Max Muyemburuko, chairperson for the Kavango East and West Regional Conservancy and Community Forestry Association, in a statement.

“Why should Recon’s water thirst for oil drilling and fracking be prioritised over the existential need of local communities, farmers and wildlife?”

The groups argue that potential draw-down of the groundwater level and contamination of water resources could significantly affect the agricultural potential and Kavango people.

Ina-Maria Shikongo, of Fridays For Future Windhoek, said shale development in the Kavango basin would contribute to more methane emissions, “raising questions about Namibia’s efforts to fulfil the climate obligations under the Paris Agreement”.