Poison pen: A report by German NGOs has criticised duplicity in the global trade in pesticides, which may be developed in the EU but sold elsewhere. (Paul Botes/M&G)

The active ingredients in hazardous pesticides, developed and brought to market by German agrochemical firms Bayer and BASF, are damaging the health of farmworkers and farmers in South Africa.

Six of eight active ingredients that have been deemed carcinogenic (cancer-causing), reprotoxic (interfering with human reproduction) and mutagenic (capable of inducing heritable genetic defects or increasing their incidence), can be found on the South African agrochemicals market — four from Bayer and two from BASF — according to a new report by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, the Inkota Netzwerk and Pan Germany.

Banned in EU, but exported

For Jan Urhahn, the programme director for food sovereignty at the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, the report, Double Standards and Hazardous Pesticides from Bayer and BASF, exposes the duplicity in the global trade in pesticides.

“The issue at hand regards pesticide products and active ingredients that are either banned or not approved in the European Union due to health or environmental concerns but that are nevertheless exported out of the EU by agrochemical corporations and are then sold in other regions of the world,” he said.

This includes the trade of pesticides and active ingredients that might be developed by European corporations, but which the companies manufacture outside the EU and sell elsewhere, he said.

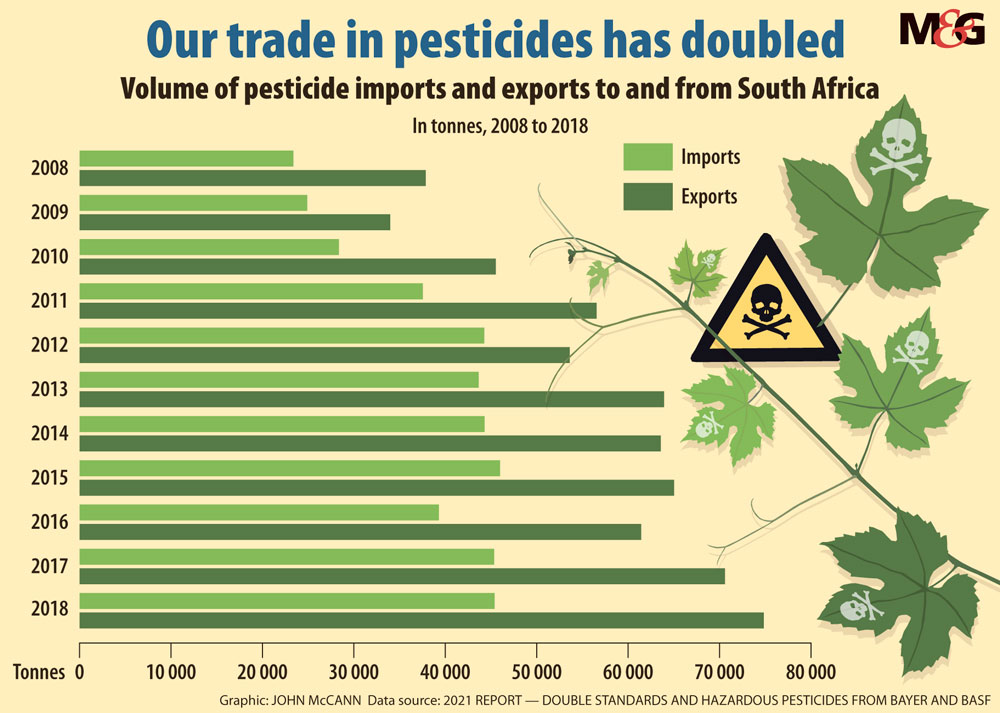

EU member countries approved the export of more than 81 000 tonnes of pesticides in 2018 that included active ingredients whose use is banned in the EU. No less than 41 of these outlawed chemicals received export licences in the same year, with most shipped to countries in the Global South, including Brazil and South Africa.

“Our current report looks at the active ingredients that have a particularly high degree of acute toxicity (are considered highly hazardous) and so-called carcinogenic, reprotoxic and mutagenic (CRM) ingredients,” said Urhahn.

“The negative effects of these highly hazardous active ingredients on the health of peasant farmers or farmworkers are the same all over the world, whether in Germany, the EU or in South Africa or the African continent.”

The “companies know very well that the ‘safe’ use of their pesticides and active ingredients in countries like South Africa is only an ‘illusion’”, he said.

The reasons for this are manifold.

“However, they accept this to make profits at the expense of workers’ health and the environment.”

‘Wall of silence’

There is an extreme lack of transparency in the local pesticide market, the report found. “For example, there is no public register that lists information on all the pesticide products and active ingredients registered in South Africa,” said the report

Employees of the department of agriculture, land reform and rural development direct enquiries to the database Agri-Intel, operated by pesticide lobby group CropLife South Africa.

“The lobby group decides by itself who is granted access to the information. The authors made repeated requests to CropLife SA for access to this data, all of which went unanswered,” the report stated.

But Rod Bell, the chief executive officer of CropLife SA, denied it was a lobby group, calling it instead a nonprofit, nongovernment industry association that enables its members to provide environmentally compatible solutions that ensure sustainable, safe and affordable food production and food security.

CropLife, he said, could not provide comment on some of the findings listed in the report as it was not within its mandate.

“CropLife SA is not a regulator, it does not approve or register any crop protection products or active ingredients, and membership to the association is entirely voluntary. In addition, it cannot comment on the fact that the department of agriculture has no available record of registered agrochemicals in South Africa, as this is entirely the mandate of the department itself, and therefore any failure on behalf of the department to provide that information is not within the control, nor the responsibility of CropLife,” he said.

“We can, however, provide clarity about the self-funded, independent database developed and operated by CropLife, namely Agri-Intel, which has no link to the government, nor is it mandated as such. As part of their membership fee, CropLife members are granted access to Agri-Intel to ensure compliance when advising or developing spray programmes, adhering to label instructions and complying with pre-harvest intervals and maximum residue levels. Non-members need to pay an annual subscription fee based on their chosen package, as is stated on the website, so as to fund the maintenance and further development of the system as there is no financial assistance from government, nor any other institution, in this regard.”

Bell said the information contained in Agri-Intel is not generated by CropLife but voluntarily submitted by the crop protection industry. He said the same information can be accessed by any person directly from the product suppliers or, in many instances, is freely available on the supplier company’s website.

“There have been instances where requests for access needed to be reviewed in order to protect against any possible data-mining instances; however, to date, we have no knowledge of a Pan representative identifying themselves as such when formally requesting information from Agri-Intel,” he added.

The department did not respond to the Mail & Guardian’s enquiries.

Professor Leslie London, a pesticide expert at the University of Cape Town’s school of public health, told the M&G it is “appalling” that the department has completely abdicated any responsibility for its stewardship role linked to pesticide regulation.

“It’s completely unacceptable that they have outsourced the function of providing information to the public to a private organisation, and not just any private organisation, but to the industry association who stand completely conflicted in this situation – where they control access to information which may be prejudicial to their business, so they stop people realising their right to information,” London said.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Lax approvals

The report found that agrochemical companies profit from the “relatively lax” approval process in South Africa.

“Many of the approved pesticide products have not been re-examined for years, and if subjected to today’s stricter risk assessment standards would likely be banned,” said the report.

This has “fatal consequences” for the region, since numerous neighbouring countries take their cues from approval decisions made in South Africa.

Health impacts

On wine farms in the Western Cape, Bayer’s insecticide Tempo SC is used on a large scale. It contains the highly hazardous active ingredient beta-cyfluthrin, which is lethal even in small doses, said the report.

“Women told us how they are compelled by the farmer to immediately enter the vineyard after he has sprayed,” said Colette Simon, the director of Women in Farms. “They are using their bare hands to handle grapes and vineyards that are still wet with the pesticides.

“Very often these farmers, like Bayer and BASF, will say ‘these chemicals are not hazardous’ but these women have reported they always have rashes and skin problems. There are a lot of women who have asthma, which develops in adulthood and they are attributing it to pesticide exposure,” she said.

Bayer South Africa did not respond to questions about their insecticides in South Africa.

Glufosinate is a component of BASF’s pesticide, BASTA SL 200.60. According to the report the product is used on citrus farms in the Gamtoos Valley and Sundays River Valley and the workers on the farms complain of headaches, sore throats, and other ailments related to the application of pesticides.

Linda Brown, the head of communications and advocacy for BASF South Africa, said it removes products from the market that it does not consider safe.

“For this reason, we do not sell crop protection products that belong to World Health Organisation (WHO) classes 1A and 1B,” she said.

Class 1A covers extremely hazardous and 1B highly hazardous pesticides.

“For this reason, we do not sell crop protection products that belong to World Health Organisation Classes 1A and 1B (high acute toxicity).

“Accordingly, we proactively removed products based on such active substances from our portfolio. Consequently, BASF no longer produces nor markets such active substances or products containing them.”

In 2014, Brown said the EU changed from a risk to a hazard-based approach when approving active ingredients.

“In contrast to the EU, most other authorities, including most Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries like Australia, Canada, Japan or the USA, apply a risk-based approach to assess the safety of an active ingredient. This confirms that when taking the exposure level into account, active ingredients can be used safely.”

There are vast differences in crops, soil, climate, pests and farming practices around the world, said Brown, and the company tailors its products for specific regional markets.

“All BASF products are extensively tested, evaluated and approved by public authorities following the official approval procedures set forth in the respective countries before they are sold.

“We are convinced of the safety of our products when they are used correctly following the label instructions and stewardship guidelines. Our employees live and work in the countries where we sell our products, and they are out in the fields with the local farmers.”