Mixed blessing: Pesticides keep crops such as watermelon (above) pest free for exclusive human consumption, but they are also potentially harmful and must be carefully regulated. (Chaideer Mahyuddin/AFP)

Pesticide lobby group CropLife SA, which represents major manufacturers, wants to oversee the licensing of scientists responsible for testing its members’ pesticides, leaked documents reveal.

This has drawn outrage from the South African Council for Natural Scientific Professions (SACNASP), the statutory body legally mandated to licence scientists, according to a joint investigation by Unearthed, Greenpeace’s investigative unit, and the Mail & Guardian.

Scientists conduct hundreds of “field trials” every year to test the safety of new pesticide products. These field trials are used to determine critical safety issues such as how soon workers can be sent into a field after spraying and how soon after spraying a crop can be eaten.

The country’s pesticides regulator relies on these findings to assess whether the products can safely be approved for sale.

Scientists may be hired by the pesticide manufacturers themselves. But they should, according to SACNASP, be accredited by the regulatory body, and this is the space where CropLife SA wants to regulate. It is a not-for-profit industry association representing the leading global manufacturers of pesticides and local firms. Part of its plan includes having “independent consultants” that are “embedded” in the office of South Africa’s pesticides registrar.

Rico Euripidou, an environmental health campaigner at groundWork, says CropLife SA is lobbying hard to position itself as “the fox in charge of the henhouse”.

“Importantly this is not just happening at our national level. Globally CropLife International is positioning itself in a similar way with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation.”

In South Africa, says Euripidou, the push for self-regulation would undermine the independence of the country’s regulatory body.

Scientists could then “minimise the harm of chemical use, including the risks associated with highly hazardous pesticides, many of which are produced by CropLife members such as Bayer Crop Science, Syngenta, BASF and Corteva Agriscience”.

Euripidou says this is a way of “outsourcing” the work of the government to consultants.

CropLife SA’s chief executive Rod Bell denies that the organisation is trying to become “approved as a scientific body” that can regulate scientists in the whole of South Africa and in all industries. “The CropLife SA mandate is only for its member companies. CropLife SA absolutely refutes the accusation that it is attempting to find a loophole for regulatory processes,” he says.

The leaked documents show that CropLife SA has been trying to push for wording that states trial scientists must be registered with SACNASP or an “equivalent” body, while pressing the registrar to approve a committee of its own members as a licencing body for trial scientists.

CropLife proposed that the body include employees of multinational pesticide firms Syngenta, Corteva and Bayer, local firms Meridian Agritech, Philagro and Bitrad Consulting, Gerhard Verdoorn, CropLife SA’s operations and stewardship manager, and CEO Rod Bell.

‘SACNASP or equivalent’

Earlier this year, the industry association seemed on track to get its plan through, the documents suggest.

In May, Verdoorn wrote to members telling them that the scheme was progressing as planned. “The registrar agreed that CropLife SA is of sound standing to be a scientific body to accredit trial operators.”

In June, South Africa’s pesticide registrar, Maluta Jonathan Mudzunga, circulated a draft of his proposed new pesticides regulations, which defined a “suitably qualified person” to conduct pesticide trials as a person registered with SACNASP “or equivalent”.

But when the document was circulated to SACNASP, it drew a furious response. On 6 August, its chief executive, Dr Pradish Rampersadh, replied in a letter to Mudzunga that “the words ‘or equivalent’ should be removed from the definition”.Pesticide trials, Rampersadh wrote, must be conducted by SACNASP-registered persons. If not, the council may prosecute individuals practising without registration.

Mudzunga produced a new draft in September, stating scientists would have to be registered by SACNASP.

This, in turn, drew an angry response from CropLife. It claimed that the regulations “will exclude a vast number of people from participating in our industry and could indeed be challenged from a point of being ‘anti-competitive’”.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

‘Counterproposals’

Mudzunga says discussions are ongoing as to whether another professional body besides SACNASP should accredit trial scientists. “As part of the review of the regulatory framework, we need to make sure the people who generate data belong or be regulated by a professional scientific body,” he says.

“It has transpired that there have been discussions and counter proposals. One was that other than SACNASP, is there any other independent professional body that we can explore? Remember this professional body must be independent of whoever is being regulated. There has been the proposal we must then consider SACNASP together with some equivalent, and this equivalent, there has been a discussion as to how it must look like.

“So, there have been documents CropLife SA has put in place about this. Again, the issue is will that meet the independence of that body? We have indicated in a later review of the regulations we’ve published is that that body currently must be SACNASP. Of course now, there are discussions about now whether it should only be SACNASP and that’s where the discussions are now,” Mudzunga says.

Rampersadh says discussions continue with Mudzunga and CropLife SA “to pursue all avenues for an amicable resolution to ensure that SACNASP is able to fulfil its mandate to the public and to government”.

Bell says a draft CropLife SA certification scheme was proposed for technical employees of CropLife SA member companies. “The draft internal documentation was in response to correspondence and a request from the registrar … to validate field trial data, as well as in response to CropLife SA member companies requesting an opportunity for their employees to become part of a self-regulating system for technical people of CropLife SA member companies.”

Bell says discussions with SACNASP are continuing over which individuals from companies represented by CropLife SA are “natural scientists” according to the Natural Scientific Professions Act. “We are confident these interactions will result in a solution that ensures compliance with the Act as well as ensuring all parties strive for the improvement of scientific standards.”

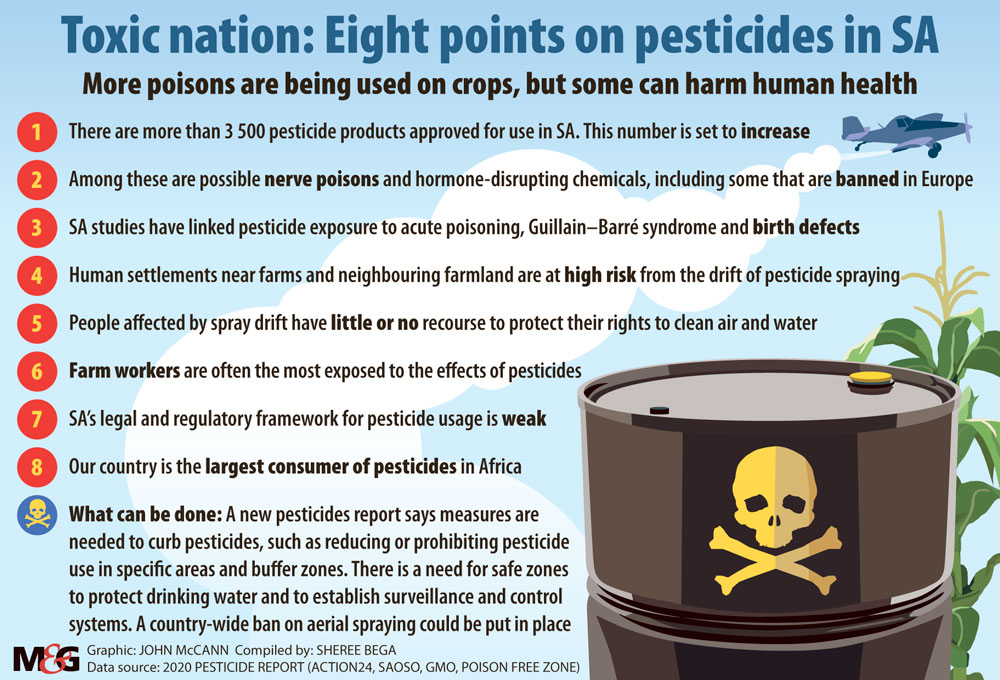

Regulations control creep

Amy Giliam, branch manager of the African Climate Reality Project, says more than 200 000 people die from pesticide poisoning every year, mostly in developing countries. “Exposure to highly hazardous pesticides, as is the case in South Africa, is linked to cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, hormone disruption, developmental disorders, and sterility. Other effects may include memory loss, asthma, hypersensitivity and allergies.”

Pesticide runoff contaminates soil and groundwater, decreases soil fertility and contributes to biodiversity loss. “All of these combined can lead to a large decline in crop yields, which is a threat to food security.”

According to public health specialist professor Leslie London of the University of Cape Town, CropLife appears to be opening the door for unregistered industry scientists. “At least, if a scientist is registered with a professional organisation, one can expect them to operate to professional standards. [Otherwise] there is absolutely no oversight over the quality of their research. They can write what they like, and present it as pukka research and nobody will be able to hold them to account if it turns out it is simply fabricated or misrepresenting data.”

Civil society has grave misgivings about the regulation of agrichemicals “given the evidence of their misuse from affected communities and the public”, says Vanessa Black of Biowatch SA. “Any review of pesticide regulations should consult with those most affected.”

Unpoison, an agrichemical policy working group, tells how agrichemical laws have not changed since 1947.

“There is little to no testing of residue levels on our local produce and the legislation that is in place to protect us is not enforced.”

Greenpeace Africa campaigner Thandile Chinyavanhu says the move by CropLife SA is a clear conflict of interest. “In no world should the pesticides industry, with clear vested interests to profit from selling poison, be allowed to regulate itself, its products or the scientists that test what is or isn’t safe to spray on our crops.

“Some of these firms already use South Africa as a ‘dumping ground’ for chemicals so toxic they’ve been banned across Europe for their devastating impacts on human health and the environment. It would be a disaster to let them capture the regulatory process,” Chinyavanhu says.

Bugs in the system: Embedded consultants

Leaked minutes from a meeting of CropLife South Africa’s “regulatory forum” in August show how it agreed to a deal with pesticides regulator Maluta Jonathan Mudzunga. The deal meant CropLife SA would pay to have “independent consultants” that are “embedded” at South Africa’s pesticide registrar’s office.

Companies applying to have a product registered for sale will be expected to pay an extra fee — on top of the “gazetted tariffs” they would normally pay for an application — to cover the cost of these embedded consultants.

The registrar’s office is “immensely understaffed”, says CropLife SA chief executive, Rod Bell, with huge backlogs.

CropLife SA’s offer to assist the registrar’s office “in clearing the backlog by finding independent resources, approved and managed by the registrar and not the industry” has precedent and is critical to food security and the maintenance of export markets, he claims.

Mudzunga says: “Some of the applications we’re receiving have data gaps so to make sure there are no delays in the applications, it may be important that such applications should be screened by somebody else … so the registrar cannot spend so much time going back to trials to request things that were supposed to be there. There’s no such intention to then say there will be people embedded in the department to replace the function of the regulator.”

Barbra Muzata, spokesperson for Corteva South Africa, says the final decision on the “granting (or not) of a registration for a plant protection product is solely in the control of the registrar”.

[/membership]