‘Life on earth is inconceivable without trees,” wrote Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. But the world’s trees, which have evolved over millions of years, are no longer able to outlast the onslaught of human threats.

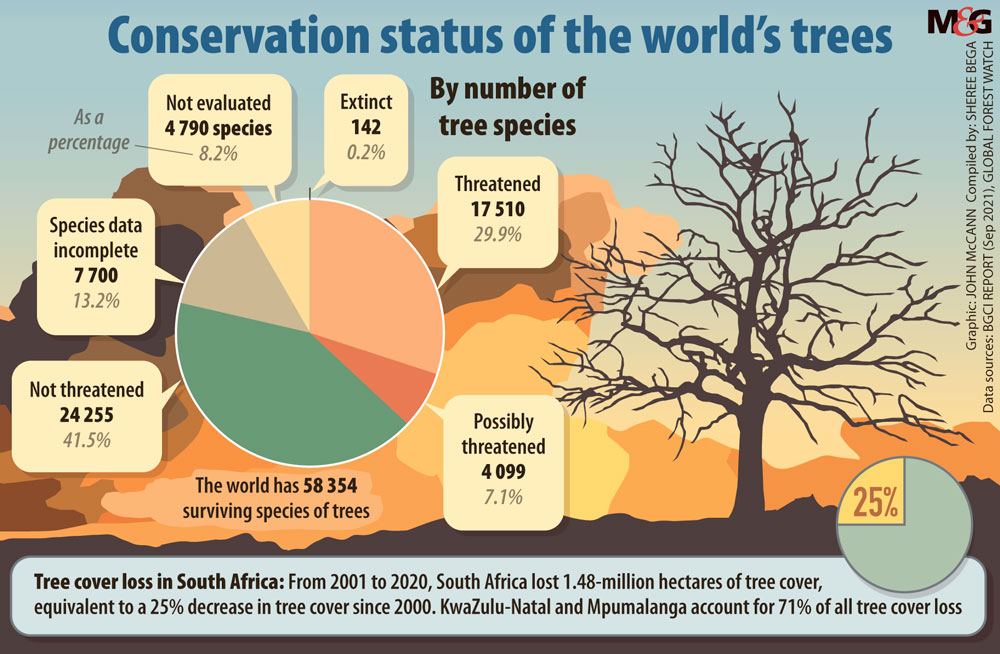

A third of the planet’s nearly 60 000 known tree species are on the verge of extinction and 142 species are extinct, warns a landmark report, The State of the World’s Trees.

A further 442 species are on the brink, with fewer than 50 specimens left in the wild. In Malawi, for example, the critically endangered Mulanje cedar, the national tree, has dwindled to a few individuals.

The report, a five-year international effort by 60 institutions and 500 experts, details the scale of the little-known botanical crisis. There are twice the number of threatened tree species globally than threatened mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles combined.

“To see almost a third of the world’s tree species under some form of threat should be a wake-up call to conservationists and decision-makers,” says Izak van der Merwe, a forestry scientist at South Africa’s department of forestry, fisheries and the environment. “So too is the [report’s] assertion that more than 40% of the world’s forests have been lost.”

Yet trees are an essential source of food, medicines, timber, fuel, and fibres and have highly important cultural, spiritual and symbolic significance, says the report by Botanic Gardens Conservation International.

They are the “backbone” of the natural ecosystem, storing half the world’s terrestrial carbon and providing a buffer from extreme weather, such as hurricanes and tsunamis. Many threatened species provide habitat and food for millions of other species of birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, insects and microorganisms.

With the bulk of attention directed to animals requiring urgent protection, the report hopes to raise awareness of the trees equally at risk and require further action to prevent extinction. A GlobalTree Portal, an online database tracking conservation efforts for trees at a species, country, and global level, has now been launched.

The interlinked biodiversity crisis and global climate change cannot be addressed without informed management of tree species.

Globally, the key culprits are agriculture for crops (29%), logging (27%), livestock farming (14%), residential and commercial development (13%), fire and fire suppression (13%), energy production and mining (9%), wood and pulp plantations (6%), invasive and other problematic species (5%) and climate change (4%), the report states. Climate change and extreme weather are ranked as emerging threats.

Van der Merwe says South Africa doesn’t face the same level of deforestation problems as countries with tropical rainforests and boasts above average diversity in tree species.

The report finds 6% of South Africa’s species are threatened. “Our threats are real and sometimes affect sensitive areas like riverine forest and mangrove forest,” he says.

“Apart from tree cutting, climatic events in southern Africa like droughts are having great impacts on certain tree species. Land use practices such as overgrazing and excluding fire actually lead to a great increase in trees in some places [indigenous pioneer species and exotic invasives], which has a negative impact on ecosystems.”

Worryingly for Africa, the report indicates more than a third of species are threatened — more than on any other continent. And although South Africa’s threatened species comprise only 61 of the 3 644 species listed as threatened in Africa, south of the Sahara, this doesn’t reveal the full picture.

“We are not only worried by the few species threatened with extinction. Our bigger concern in South Africa is the impact of removal of keystone species on their habitats … that this has on the liveability of our environment, even if such species are abundant.”

These species include camel thorn and leadwood trees, which occur over large woodland areas in high numbers in the country and are protected through a permit system. They are harvested for the huge braai wood market and removed in their thousands by mining, says Van der Merwe.

Local research on camel thorns has shown that where large specimens are removed, the biodiversity of fauna, especially birds and reptiles “drops drastically and it leads to harsher, less liveable and less productive habitats”.

The collapse of ecosystems is echoed as a global concern. The report cites the recent unprecedented fires in California, southern Australia, Indonesia and the Amazon, and details how large areas of forests are undergoing mass mortality events because of drought, heat stress and the increased incidence of pests and diseases. “It is not only individual tree species that are declining and being lost, but entire communities of species with which they are associated and the ecological interactions that occur between them.”

Van der Merwe says the dying out of big baobabs in Southern Africa is a sign of climate trends to more and longer droughts, while the development of mines, agriculture and solar farms cause the loss of thousands of hectares of habitat and millions of trees each year in South Africa.

The polyphagous shot hole borer has attacked a variety of trees, particularly in urban areas “with some tragic loss of old oak trees” in towns such as George.

A third of valuable timber tree species globally are under threat.“In South Africa there has been a worrying trend of increasing pressure on protected tree species like matumi, leadwood and teak, cut into slabs and sold for furniture timber, often illegally,” Van der Merwe says, adding how this has led to arrests and timber confiscation by the department. The enormous tropical timber trade, much of which is illegal, is climbing, too.

“In South Africa such timber from central and Southern Africa crossing our borders in transit to harbours for export has greatly increased.”

There are signs of hope. “In Malawi, the Mulanje cedar is being restored. In South Africa there is a project to restore the Clanwilliam cedar in the Cederberg and the highly successful propagation of the threatened pepperbark,” says Van der Merwe.