In 2020, a large plastic sack in the ocean became entangled on Maia the turtle's flipper causing part of it to rot away. (Photo: South African Association for Marine Biological Research)

With one less flipper and in just eight days, a young, courageous green turtle called Maia has travelled more than 600km from South Africa to Mozambique.

In December 2020, she was found stranded on the beach in the Isimangaliso Wetland Park in northern KwaZulu-Natal. A large woven plastic sack was wrapped around her left front flipper, which caused severe necrosis and the partial loss of that flipper.

On 13 December, Maia was released in the Isimangaliso Wetland Park, after two years of rehabilitation at the South African Association for Marine Biological Research (SAAMBR) Sea Turtle Hospital at uShaka Sea World.

Her carers never anticipated that Maia was going to be an “absolute swimming sensation”, but by 21 December, she had made her way up to Mozambique “at an average of a half marathon swim a day”.

By Christmas, she was already in the warm Maputo Bay, where she is still criss-crossing this protected site, now known as the Maputo National Park, which is viewed as an extension of the Isimangaliso Wetland Park.

Entangled in plastic

Malini Pather, principal lead aquarist responsible for quarantine, the animal hospital and the sea turtle rehabilitation programme, recalled how an Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife staff member had made an eight-hour return trip to deliver the very tired turtle to the hospital’s rehabilitation team two years ago.

“Maia was exceptionally beautiful,” she said. “She had the cutest face and the most beautiful carapace. She had these radiating lines that went out; you see them in other turtles, but she was just gorgeous.”

For Pather, the first step was to cut away the larger portion of the woven plastic. She remembered how difficult it was to look at the injury. “As we removed the larger portion of the bag, we were able to see that the flipper was almost completely gone already, it had rotted away. That poor animal had been like that for a while.”

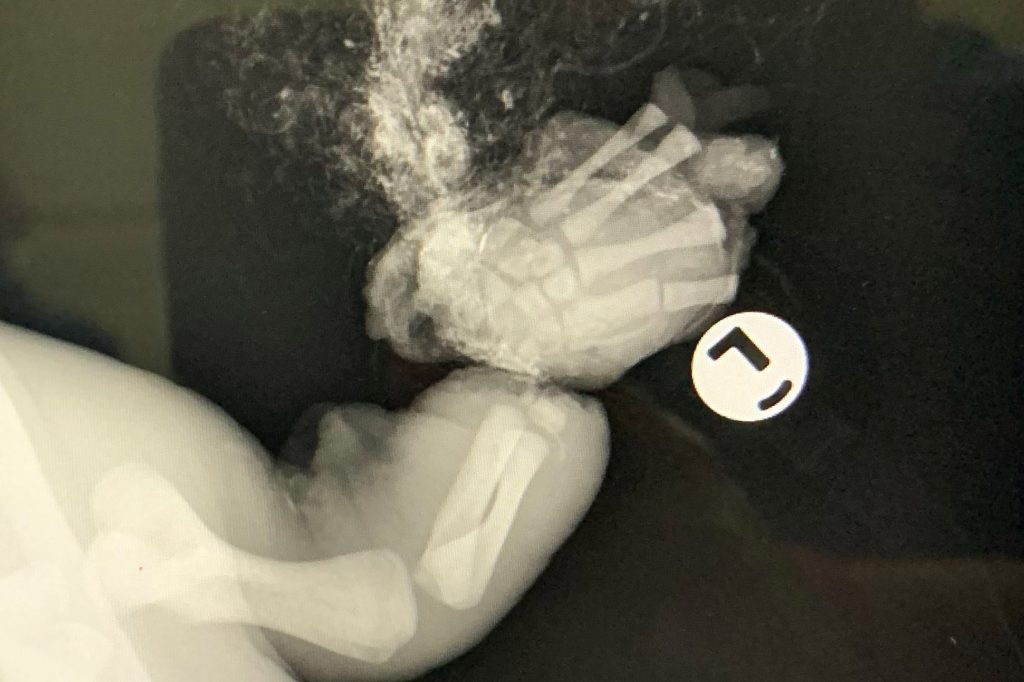

When X-rays were done the next day, the same woven strips of plastic were spotted in Maia’s system. “This animal was obviously trying to free itself and was biting the plastic to try and get it off. And she had ingested some.

“Maia was a very lucky turtle to have found her way to us. She was just as feisty as she was beautiful and she healed really well. That flipper could have become infected, there’s a very good chance that she wouldn’t have made it had she not managed to get veterinary support. The plastic bag would have prevented her from diving. It would have made her an easy target for predators.”

Fighting spirit

She was named Maia, the Maori word for courage, because “she displayed true courage, bravery and a headstrong attitude to recover”, said the SAAMBR.

The juvenile turtle underwent extensive rehabilitation, including surgery, antibiotics, various radiographs and “lots of tender loving care” until she was medically cleared for release — albeit with one less flipper.

“We have husbandry checks and veterinary checks, each of those involve a series of tests to make sure the animal will be able to survive in the wild — how they swim, get food and what their bloods look like compared to other wild turtles of the same age. Maia passed with flying colours,” Pather said.

It is quite common to see turtles in the wild with partial and even complete flipper amputations, most often because of shark bites or entanglements, which made the team optimistic about her release.

“The best part was being able to satellite tag her — satellite tags are exceptionally expensive,” Pather said.

Along with Maia, they released a similarly-sized green turtle, Aurora, who was found stranded at Scottburgh last year, suffering from a serious infestation of leeches, and had recovered. Aurora, too, was fitted with a satellite tag.

“We released two green turtles, one with four flippers and one with three at the same spot because we thought everybody’s a little uncertain, but we have done our homework. So, let’s tag them and compare the habitat use and how fast they travel and see if there is a difference between three flippers and four flippers. Let me tell you little Maia did not let us down. She outswam everyone and had travelled 700km the last time I checked.”

‘Enjoying the Mozambican life’

The Maputo National Park boasts rich species diversity and is home to 104 species of conservation significance, such as sea turtles and dugongs. Inhaca Island, which falls within this area, has the largest seagrass coverage in the world, perfect food for vegetarian green turtles. It offers critical inter-nesting, nesting and mating grounds for loggerhead and leatherback sea turtles.

Maia “is obviously enjoying the Mozambican life”, said Pather. “She is in the reserve and obviously in the reserve there will be an abundance of food. She will be feasting and enjoying herself and we cannot wait to see where she goes and where this journey takes her.”

The SAAMBR said it is “incredibly proud” of Maia’s journey so far. “As a young sea turtle, she still has many years ahead of her before reaching reproductive age and she could very well decide to hang around in this perfect turtle habitat. The nearest green turtle nesting sites are about 1 000km northeast of her, which are not too big a journey considering how well she travels.”

Through the small satellite tag attached to her carapace, the organisation hopes to be able to track her movements and spatial ecology for at least a year, together with the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment. This will enable its team to analyse the post-rehabilitative movement and performance of sea turtles with flipper amputations.

Pather said they are seeing more and more cases like Maia’s.

“One of the things we also do is go through the faecal samples of these animals. It’s not that glamorous but we have to figure out what they are eating because that would help us to get them to eat …. We look for any abnormalities and sometimes there’s fishing line, and pieces of plastic and all sorts of weird and not-so-wonderful things. It is quite devastating — you have a case you work so hard on and you try everything and you just find this animal full of plastic.”

People often walk away thinking they can’t make a difference, but it’s not true, Pather said. “If every single person were to just change one thing — no more plastic straws, or not using plastic cups, or no more plastic bags or polystyrene, one change in behaviour like that is going to make a difference to the lives of these animals and the environment.”

[/membership]