Schoolchildren pass an abandoned mine pit on the outskirts of Wesselton, Ermelo’s satellite township. Photo: James Puttick / New Frame

Coal is a booming business for people in or near eMalahleni (Ermelo), the commercial hub of Gert Sibande district municipality in Mpumalanga. Situated about 200km east of Johannesburg, the area is home to Camden coal power station, scheduled to be shut down by 2025.

“Coal is the heritage of this province, it is the backbone of our economy. It’s an undeniable fact,” says Philani Mngomezulu, founder of an established community-based greening project called the Khuthala environmental group.

He said almost 80% of the more than 80 000 residents working and generating income in eMalahleni are employed at Eskom, and at Transnet, the state-owned transport company. Camden is one of 12 coal power stations in Mpumalanga scheduled to be decommissioned in the coming years, most of them by 2035.

“As an environmental group, we are clear about the impact of coal on our environment, in particular climate change and pollution. However, as the community of Ermelo we will only be in agreement with the energy transition if it is going to impact positively on the local people,” he says.

The coal-mining regions in Mpumalanga are at the front line of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition (JET) process, which aims to repurpose coal power plants and coal-mining lands, to build economic diversification, and to assist with the transition of workers and other people to greener energy. (See South Africa’s energy transition rises in the east.)

But, said Mngomezulu, people are in the dark when it comes to the transition because the government is not bringing consultations to them.

“The consultation is very poor,” he says. “We’ve been saying to the Presidential Climate Commission [PCC] that they must come and do a proper consultation in Ermelo because people here are dependent on coal. So if we are going to shut down the power stations and any other coal mines without informing the community, that’s a bit unfair.”

The PCC is a multi-stakeholder body set up by President Cyril Ramaphosa to “oversee and facilitate a just and equitable transition towards a low-emissions and climate-resilient economy” in South Africa.

Over the past two decades the Khuthala environmental group has been working on small-scale energy transition programmes, food gardens and providing awareness programmes on the JET, but most people lack the resources to get involved.

“Mpumalanga’s problem is that we don’t have the resources and space to manufacture solar systems, and we are not sure how we will be able to take part meaningfully in the just transition,” Mngomezulu says.

Meanwhile, people are living in “energy poverty: most of our informal settlements don’t have electricity, so they rely on coal, and some are able to profit from coal sales”, he says.

The downside of phasing out coal: Given Masina says his coal yard will have to close and retrench employees from the local community. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

The downside of phasing out coal: Given Masina says his coal yard will have to close and retrench employees from the local community. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Artisanal mining

Data collated by the Oxpeckers #MineAlert tool shows that at least 227 government-licensed coal mines surround eMalahleni.

The area is also home to more than 3 000 artisanal miners who contribute to the local economy, pay rent, buy clothes and provide jobs.

Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Gwede Mantashe published a policy in 2022 that promotes a formalised artisanal and small-scale mining industry that can operate optimally and sustainably while contributing to the economy through taxes and royalties, job creation and eliminating illegal operations.

This policy mentions that illegal mining by “zama-zamas” is distinguished from artisanal mining by people who want to participate in the industry to improve their livelihoods and contribute to the economy and growth of the industry.

Artisanal miners are worried that, just as they are starting to operate legally with permits in hand and the new policy in place, the government is now planning to shut down everything coal-related.

Given Masina says the downside of phasing out coal is that businesses such as his will have to close. He started a coal yard in Wesselton, eMalahleni’s satellite township, in 2011 that sells coal to locals. He also employs people from the township.

“I supply the rural areas on the outskirts of Ermelo,” he says. “It’s totally wrong for the government to close the coal mines. People are being retrenched left, right, and centre. Do we vote for a government that starves people? Would it be fair for us to vote for a government that retrenches people?”

Masina says they had not heard anything from the government about consultations with the community. “Look, if they decide to phase out coal, this means I will also have to retrench the employees I have so far employed.

“There is no doubt that this transition is causing havoc in South Africa. At the moment, power stations are being bombed because of this transition that is not being explained properly to the people of the country,” Masina says.

NAAM’s Zethu Hlatshwayo: ‘Renewables need to subsidise coal so that we can have electricity in our country.’ Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

NAAM’s Zethu Hlatshwayo: ‘Renewables need to subsidise coal so that we can have electricity in our country.’ Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Mixed energy transition

Zethu Hlatshwayo, the national coordinator of the National Association of Artisanal Miners (NAAM), says that as an association and as part of eMalahleni, they stand for a just mixed energy transition.

“As much as we are transitioning, we cannot desert or destroy coal altogether because renewables need to subsidise coal so that we can have electricity in our country. We need them both,” he says.

According to Hlatshwayo, several of the abandoned mines the NAAM members are operating are still mineral-rich and others need to be rehabilitated because they are dangerous.

“They’re sitting idle, some have been left for 20 years and more. Some are not safe; they’re claiming lives because they are collapsing, because of flooding, and because there are gases. We are waiting for those to be rehabilitated.”

Hlatshwayo says artisanal miners are formalising the sector to sustain themselves and their families, and they are fighting for their right to work. “We’ve been instrumental in pursuing the government to make sure we have this policy in place.”

The artisanal miners benefit the community at large, he says. “Artisanal miners run our local and township economy since they mine coal and deliver it to coal yards owned by the community using transport owned by the community.

“The government cannot close down all of the coal mines because there are 22 products — such as cement, aluminium and hydrogen, to name a few — that are produced by coal alone. If you are going to kill Eskom or you’re going to kill the mines, this means you are going to kill the other industries that are dependent on coal for other products, and these are products we need.”

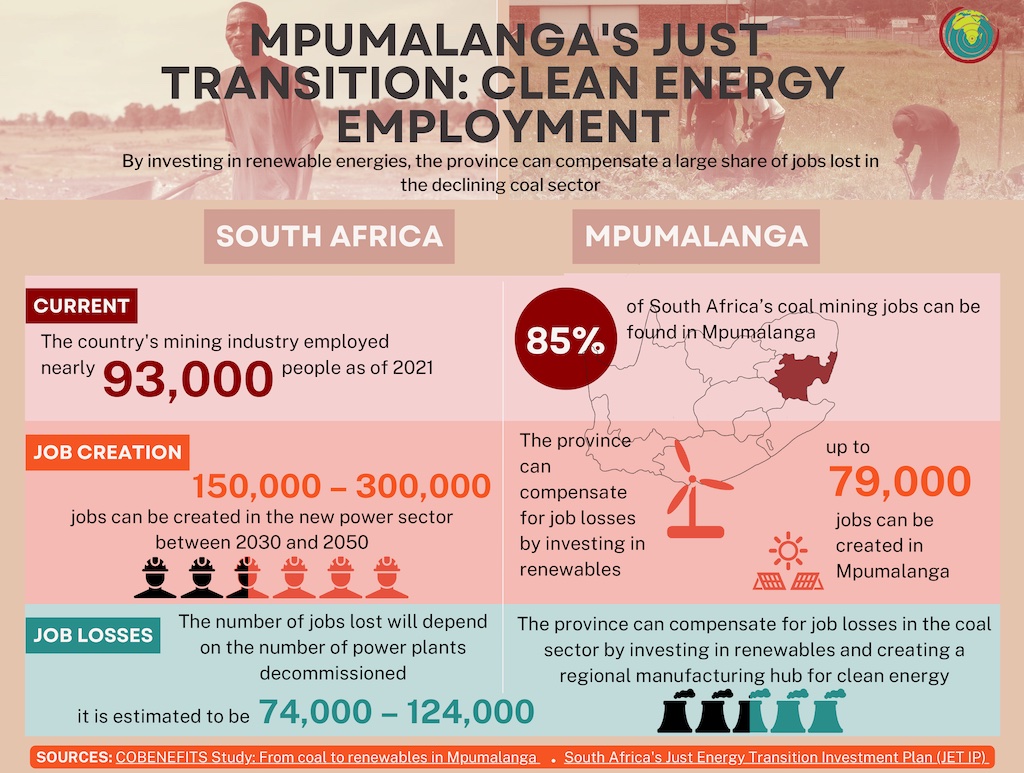

Supporting what Hlatshwayo is saying about the township economy, the JET plan states that 85% of South Africa’s coal-mining jobs can be found in Mpumalanga. The provincial economy is heavily dependent on coal for employment, the municipal rates base and community development activities.

According to Hlatshwayo, the energy transition in eMalahleni will only be successful if the government takes its programmes to the people and explains t what the programme is and how it will benefit them.

Credit: Oxpeckers

Credit: Oxpeckers

Employment opportunities

The JET plan, released in 2022, states that more than half the youth in Mpumalanga are unemployed and the coal value chain decline will further narrow employment opportunities as the sector downscales.

It shows that the coal sector provides direct jobs to almost 90 000 people in mines and power plants in the province, and indirect jobs for people who provide goods and services to the coal sector, which supports a significant portion of induced jobs and other economic activities.

Downscaling of coal plants and stagnant exports mean that young workers are not entering the coal-mining workforce as they would have otherwise, according to the JET.

Eskom says the implementation of the JET is envisaged to create some 300 000 jobs in the renewables value chain. “This represents a net jobs gain,” said an Eskom spokesperson in response to Oxpeckers’ questions.

Research by the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies published in 2022 indicates that in South Africa as a whole, job creation through renewables could exceed anticipated job losses in the coal sector.

In Mpumalanga, not all job losses in the fossil fuel sector can be replaced by clean energy jobs. Under an ambitious decarbonisation scenario, these net losses can be minimised.

The report states the two most important technologies for the energy transition in Mpumalanga will be wind and solar photovoltaic energy, which will also make the largest contributions to job creation: up to 43 000 jobs in solar PV and 28 900 jobs in wind energy by 2030.

Sifiso Hlatshwayo was an employee at Camden from 2019 until he was retrenched in December 2021. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Sifiso Hlatshwayo was an employee at Camden from 2019 until he was retrenched in December 2021. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Meaningless figures

For people such as Sifiso Hlatshwayo from Wesselton, these figures are meaningless. The 30-year-old former Eskom machine operator was an employee at Camden from 2019 until he was retrenched in December 2021.

He says he is aware of other retrenchments at Komati power station “because of this transition. It doesn’t make sense that the transition will create more jobs while we just got retrenched and are doing nothing at home.

“When is it going to create the jobs the government is talking about? I want to work now.”

Hlatshwayo says he hasn’t seen or heard about government consultations, and that it is important for the government to use financial pledges from the international community to open training facilities to train and reskill people.

“The government should have reskilled a lot of employees instead of retrenching them,” he says. “There should be learnerships for out-of-school youth about this so that people can qualify to work in the transitioned power plants.”

Reskilling programmes

While people on the ground who spoke to Oxpeckers are unaware of reskilling programmes, Eskom says people employed at power stations due to be decommissioned are “being trained to obtain skills in the renewable industry so they may be able to manufacture, install and service the renewable energy components required to operate the repurposed power stations”.

“To achieve this end, and in partnership with the Cape Peninsula University of Technology’s South African Renewables Energy Technology Centre and recognised labour unions represented at Eskom, Eskom has established an accredited training centre at the Komati power station,” an Eskom spokesperson, who asked not to be named, said in response to Oxpeckers questions.

“Those whose skills are required at other coal-fired power stations get transferred to those stations to meet the staffing requirements there. As part of the shutdown plan, extensive socio-economic studies were conducted which included widespread consultation with all communities around the affected power stations.”

And, most importantly, he said, Eskom assures all its employees that “no Eskom employee will lose their jobs because of the JET”.

The spokesperson said employees who no longer work at Komati had either resigned, retired or were transferred to other stations.

“Eskom plans to use its limited funding to catalyse the construction of renewables plants across the country,” the spokesperson said. “This is demonstrated by the leasing of land at Eskom power stations to allow private participants to rapidly bring online new generating capacity, inter alia.”

Michelle Cruywagen, the just transition and coal campaign manager at environmental justice NGO Groundwork, says unions set out processes for a just transition in 2018, “but the business and mining sectors didn’t really come on board in assisting with facilitating the transition, even though they are obliged to do so legally through the social and labour plans”.

“This can be coordinated through the Minerals Council [a mining industry employers organisation], and the unions who generally negotiate wages and retirement plans should have been leading the way forward,” she says.

Cruywagen maintains that the consequences now are that the transition is not being managed properly, and the job losses aren’t being mitigated because of poor management and political will, which puts people in a vulnerable position.

“It’s fine to reskill people, but employment is actually the thing that people need,” she says. “Part of what we’re pushing for is to get local government involved so that they drive the message, raise awareness and facilitate engagement on the issues of a just transition at a local level.”

In the dark: Ward councillor Thulani Madlala (centre) with Philani Mngomezulu (left) and another member of the Khuthala environmental group. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

In the dark: Ward councillor Thulani Madlala (centre) with Philani Mngomezulu (left) and another member of the Khuthala environmental group. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Local consultations

Thulani Madlala is a ward councillor in the Msukaligwa municipality. He says he is waiting to see how the transition will assist the local poverty-stricken people.

“We are waiting for the JET to be explained to the masses of our people on the ground. We hope that this programme doesn’t negatively affect the unemployment rate that is already here because, if that’s the case, our people are going to be against the transition,” Madlala says.

“Our municipality is reliant on coal in terms of jobs, business opportunities and survival. Let renewables come into play, but don’t phase out the coal so that our people can continue to make a living.”

Madlala worries that the JET will cause a higher unemployment rate in Mpumalanga, particularly in eMalahleni. “We are very disappointed that some decisions come in a top-down approach. Right now, we are experiencing electricity challenges and are told that a just transition will solve the problems.

“We hear that reskilling is already taking place, but where? It is important that the government educate the public about the transition so that they understand how it is going to happen and how it will affect them,” he says.

Blessing Manale, head of communications at the PCC, says the commission is involved in a series of consultations to make recommendations on the country’s long-term energy plan.

He says the role of the PCC in coal-affected communities is to facilitate dialogue, provide advice to the government and support the overall efforts of South Africa meeting its global climate commitments.

“We had consultations in Secunda, eMalahleni and Carolina. In all these engagements there were representatives from various organisations based in Ermelo,” he says. “We appreciate that not only the PCC must drive these consultations but other partners on the ground need to engage and address practical challenges to ensure justice for all communities.”

In terms of new job opportunities, Manale says the PCC is working with various agencies in Mpumalanga to discuss green economy opportunities in the province. “We have appointed a dedicated manager in the PCC and will soon appoint a senior manager based in the office of the premier to facilitate and coordinate various programmes around economic diversification and job creation.”

Artisanal miners: These women say they feed their kids with the money they make from selling coal. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Artisanal miners: These women say they feed their kids with the money they make from selling coal. Photo: Thabo Molelekwa, Oxpeckers

Green economy

Nkosinathi Nkonyane is interim executive of the Mpumalanga Green Cluster, set up in 2022 “to unlock and unblock economic opportunities in the green economy, with the aim of making a contribution to regional economic diversification and job-creation efforts”.

As the country reduces its dependence on coal there will be marked effects on specific regional economies, and intervention is required to ensure that the transition to a low-carbon future is equitable. “While the just transition will be a complex process, involving change at levels across the nation, there is value in piloting projects in hotspots where the need is most urgent,” he says.

The Mpumalanga highveld region was identified as such a hotspot because it is home to the majority of coal-fired power stations and coal-mining activities. The provincial government has been proactive in exploring opportunities in the green economy for growth and support, he says.

“These opportunities can smoothe this inevitable economic transition. There are a host of potential initiatives; for example, the opportunities presented by repurposing land on ultimately decommissioned mines and coal-fired stations to pivot to renewable energy production, utilising the existing transmission assets in the region.”

The Mpumalanga region, Nkonyane says, has strategically prioritised using a cluster development model to unlock opportunities in the green economy. “Such development happens through engagement at the intersection of government, business and academia — the triple helix nexus. Independent triple helix clusters have been identified globally as a strong instrument for the green and hi-tech transitions,” he says.

Thabo Molelekwa is a freelance health and environmental journalist, and an alumnus of the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker training programme. This investigation was supported by the African Climate Foundation’s New Economy Campaigns Hub.

This article was first published by Oxpeckers.