While there are compelling arguments for transitioning to renewable energy, including environmental benefits, economic diversification, and alignment with global climate goals, there are also significant issues related to economic dependence on fossil fuels, energy access, and transition costs. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center”

For workers in the coal industry such as Nelly Sigudla (above), the transition to green energy sources in Mpumalanga is difficult to welcome. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

For workers in the coal industry such as Nelly Sigudla (above), the transition to green energy sources in Mpumalanga is difficult to welcome. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

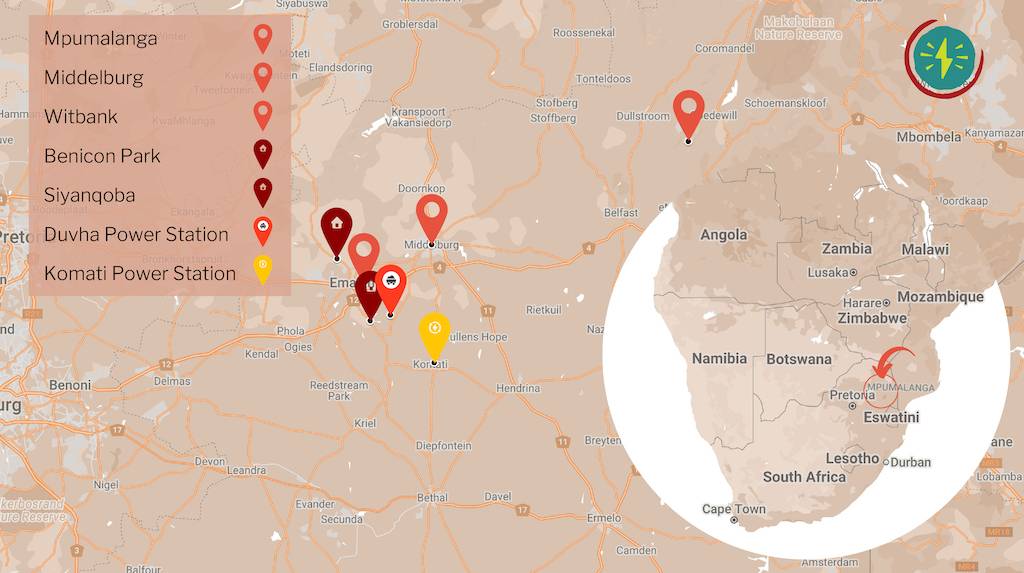

Nelly Sigudla, 41, a qualified fire watcher and part-time control room operator at Duvha power station in Mpumalanga, South Africa’s energy capital, worries for her future when her main source of income gets unplugged.

The mother of four lives in Benicon Park, an informal settlement next to the coal-fired power station that is scheduled to be decommissioned by Eskom between 2031 and 2034.

Like many employees in the coal-mining industry, Sigudla fears her qualifications won’t be enough in the near future when renewables take over from coal as South Africa’s primary source of new energy, and that she will be unemployable as a result.

The country, which depends on coal for about 85% of its electricity, is home to one of the largest energy experiments in the world — an $8.5 billion deal with a group of nations including the US, the UK and EU members — to transition towards renewable energy.

South Africa will have to redirect coal workers into new jobs in the renewable energy sector, such as construction, electrical engineering and information technology (IT).

An investigation by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Climate Home News found a major skills gap in coal-reliant communities and a lack of clarity on how funds for reskilling will be implemented.

Sigudla said the transition to green energy sources in Mpumalanga was difficult to welcome as it could bring even more poverty. The region has a soaring unemployment rate of 38%, and more than 100 000 jobs depend on coal.

“When the renewable sector kicks in, what fire am I going to watch?” Sigudha asks. “No one has come to the communities to tell us about new skills programmes that we can follow to acquire skills that will be needed in the future.”

Reskilling programmes

The Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP), a document that is guiding South Africa’s move to renewables, includes an investment of nearly R2.7 billion for reskilling programmes across the country.

In Mpumalanga, R750 million is allocated to “investing in youth” — including education, training, work experience and placements — and R5.6 billion to “caring for coal workers”, which includes re-skilling, redeployment, placement and temporary income support. Funds would not only come from the JET partnership, but also from government budgets, venture capital and multilateral banks.

According to the JET-IP, the government plans to set up a national skills hub to advise on reskilling needs, and R1,6 billion will be allocated to creating pilot training centres known as “skills development zones” in Mpumalanga, Eastern Cape and Northern Cape provinces.

These pilot zones will be run by technical colleges and support the development of new skills and courses, aiming to “ enhance the employability of graduates”, says the JET-IP.

One proposal to set up facilities for the training centres is to use old decommissioned coal plants. This was one of the options for the Komati power station, the first to shut down in October 2022, according to a report by the environmental justice organisation GroundWork.

Details about how these training centres would become operational are scarce.

Development zones

Blessing Manale, spokesperson for the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC), an independent multi-stakeholder body established by President Cyril Ramaphosa to oversee the country’s transition, was unable to indicate when the skills development zones will start operations.

Additionally, he acknowledged that skills development is severely under-prioritised, adding that “all stakeholder groups have raised this as a fundamental weakness in the JET-IP”.

“In the PCC’s view, much work needs to be done, both to quantify the needs for skills development and to upskill the workforce and new entrants — in particular youth and young women,” Manale said.

It will also require a deep transformation of the adult basic education system, artisanal skills development and curriculum revision in the tertiary education system.

“The transformation of the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges, as well as the sector education and training authorities (Setas), is fundamental,” Manale said.

The PCC in partnership with the department of higher education and training, and the energy and water Seta are rolling out a programme around skills capacity and human capital required for a just transition, he said.

But there needs to be more clarity on what types of skills will be prioritised during the planned repurposing of coal-fired plants in Mpumalanga, not just in relation to labour retraining but also skills needed to deliver transition projects.

“This gives rise to questions around who will provide the training required for upskilling workers in the coal value chain, design curricula for educational institutions where skills development will take place, and how this can be funded,” Manale told Oxpeckers.

Benicon Park is an informal settlement situated next to the Duvha coal-fired power station in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province

Benicon Park is an informal settlement situated next to the Duvha coal-fired power station in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province

Vocational training

Mpumalanga has three technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges that fall under the department of higher education and training (DHET). They focus on “preparing students to become functional workers in a skilled trade”.

These colleges, based in Ehlanzeni, Gert Sibande and Nkangala districts, provide practical skills training for the mining and fossil fuel industries, among other courses. At the start of the year, the department reported that more than 500 000 students had enrolled at TVET colleges countrywide.

During the Mpumalanga 2023 state of the province address, it was announced that the province had“partnered with various Setas in diverse trades. Setas encourage skills development in various economic sectors, including construction as well as energy and water.

Oxpeckers emailed the three TVET colleges, the DHET and several other tertiary institutions in the province to ask how skills development courses currently on offer could be applicable to the green energy sector. They were asked about the types of programmes offered, how many students are registered for these and whether there was any government funding to help improve access to professional skills development programmes in the renewables sector.

Similar questions were also sent to Eskom’s Academy of Learning and the South African Renewable Energy Technology Centre. Despite numerous follow-up phone calls, no responses were received at the time of publication.

The curricula of the TVET colleges and other educational facilities need to change to achieve the energy transition, said Professor Victor Munnik, co-author of the “Contested Transition” report released by GroundWork.

Training and reskilling for renewables must be “fit for purpose”, he said. “It should be aimed at a society that lives on renewable energy and understands how it works. There are specific specialised skills involved; for example, for the grid to become a smart grid it has to integrate many technologies.”

Changes in the education system need to include school curricula “to prepare young people not just to work in the new economy but to actively shape it and be part of it”, Munnik said.

Wendy Poulton, secretary general of the South African National Energy Association, added that there is a scarcity of specialist technical and managerial skills in the renewable energy sector. “This will require the education, training and upskilling of engineers and technicians to shift into renewables,” she said.

Happy Sithole, NUM health and safety chairperson in the Highveld region and an Eskom shop stewart, says he has no knowledge of skills development zones in Mpumalanga. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Happy Sithole, NUM health and safety chairperson in the Highveld region and an Eskom shop stewart, says he has no knowledge of skills development zones in Mpumalanga. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Union concerns

The regional chairperson of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in the Mpumalanga Highveld region, Malekutu Motubatse, is concerned that the courses offered at TVET colleges and other education facilities still produce learners that will be unemployed in the near future.

“Next to each power station, there is a coal mine that is used for the purpose of providing coal to the power station,” he said. “So the reskilling should be a reskilling of everyone. If the government is talking about reskilling, who is going to be reskilled, Eskom employees or mine employees? Let’s assume that it talks to Eskom employees, then where does it leave the coal mine workers?”

Happy Sithole, NUM health and safety chairperson in the Highveld region and an Eskom shop steward, believes not many artisanal coal miners will be employed in the renewables sector.

“We are talking about artisans, a job that pays well. If you change from coal to renewables, what’s going to happen to them?”

Sithole said he has no knowledge of skills development zones in Mpumalanga.

“We find ourselves trying to understand what this is, because as NUM we have not seen any development.”

NUM was also unaware of a training facility that is supposed to be set up at Komati power station as a model for repurposing, Sithole said.

“We have not heard of Komati becoming a training facility. All we know about Komati is that there is intent to demolish it. There’s a lot of information that needs to be cleared up, and it’s difficult to get answers,” he said.

Gaylor Montmasson-Clair, a senior economist at Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS), an economic research institution, said Eskom’s skilled workforce has a higher chance of finding alternative jobs in other industries, such as electricians, for example.

But coal miners might not have the same luck.

“To be blunt, we must stop the delusion that the bulk of people who are employed in coal mining are going to be employed in renewable energy. That narrative just makes no sense,” Montmasson-Clair said.

Benicon Park silhouettes Duvha power station, scheduled to be decommissioned by Eskom between 2031 and 2034. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Benicon Park silhouettes Duvha power station, scheduled to be decommissioned by Eskom between 2031 and 2034. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Construction jobs

Peter Venn, chief executive of Seriti Green, said the transition will create more jobs in the construction sector in the coming years.

“We see a positive job growth in the renewable space for the next 10 years through the construction period,” he said.

Seriti Green is an offshoot of a mining company and will soon begin construction on South Africa’s largest wind farm in Mpumalanga, with power supply due to come online by 2025.

With Seriti being on both sides of the transition from coal mining to renewable energy supply, Venn emphasises the importance of training programmes for the skills required in the renewable sector.

“The Cape Peninsula University has partnered with Komati power station and Eskom to deliver skills in Mpumalanga. And there are other organisations offering significant renewable energy skills,” he said.

“Renewables require across-the-spectrum skills. All the back-office skills are required, civil and electrical skills are required; it goes into IT, security, data analytics, preventative maintenance,” Venn said.

Middelburg resident Emanuel Marutle: ‘The current education system is not even able to provide skills for learners to work in the coal-mining sector, so how will it equip people with the skills needed in the renewables sector?’ Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Middelburg resident Emanuel Marutle: ‘The current education system is not even able to provide skills for learners to work in the coal-mining sector, so how will it equip people with the skills needed in the renewables sector?’ Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Young workers

According to the PCC, workers in the coal-mining sector are relatively young, with a median age of 38 years. About 90% of those employed in Mpumalanga are semi-skilled (74%), or low-skilled (17%) workers.

The urgency for the skills they will need to diversify is heightened by the fact that transition planning is developing in the context of already high unemployment, poverty and inequality, the PCC says.

“These dynamics make skills diversification more complex as the just transition ought to manage job losses and create employment opportunities in a country with an unemployment rate of 33.9%,” said Manale.

Emanuel Marutle, a resident among the coal fields in Middelburg, told Oxpeckers he is worried the education system in Mpumalanga doesn’t have the resources to help affected workers gain practical skills to weather the transition.

“The education system is not even able to provide skills for learners to work in the coal-mining sector, so how will it equip people with the skills needed in the renewables sector?”

Marutle said during a community consultation about the transition held “by government people from Johannesburg” in 2022, locals were promised that people from their municipality would be taken to undergo training for the renewable sector. This has not happened, he said.

Given Masina, another resident and a member of the Khuthala environmental care group, said he hasn’t heard anything about any reskilling, training, or skills development in Mpumalanga.

“Our kids are studying in the fields of coal, but coal is dying. People will be left without knowing what they can do,” he said. “If people are skilled, they can transfer skills to other people in the communities so that they have chances of being employed.”

This investigation by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism in partnership with Climate Home News, was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center.

The Oxpeckers #PowerTracker project is supported by the African Climate Foundation’s New Economy Campaigns Hub.

This article was first published by Oxpeckers.