#NotOnOurWatch youth ambassador Kiera King.

If every wild breeding African penguin had a seat in the Ellis Park Stadium in Gauteng, it would only be a third full.

“Imagine that,” Judy Mann, a founder of the #NotOnOurWatch African (#NOOW) penguin survival campaign told a webinar hosted by the campaign on Friday. “It wouldn’t even be a rugby match full of African penguins,” Mann said.

The campaign unveiled shark expert Sophumelela Qoma and Keira King, 17, as its two new youth ambassadors.

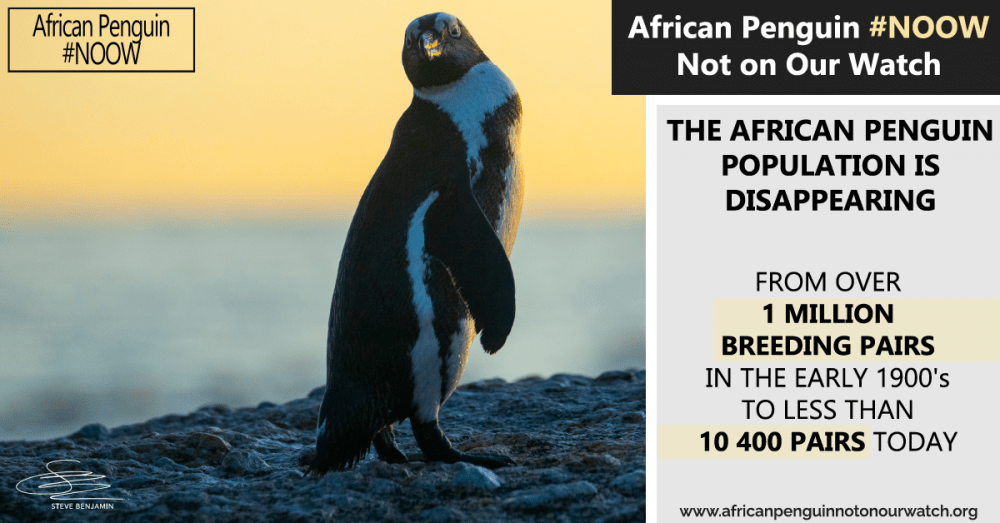

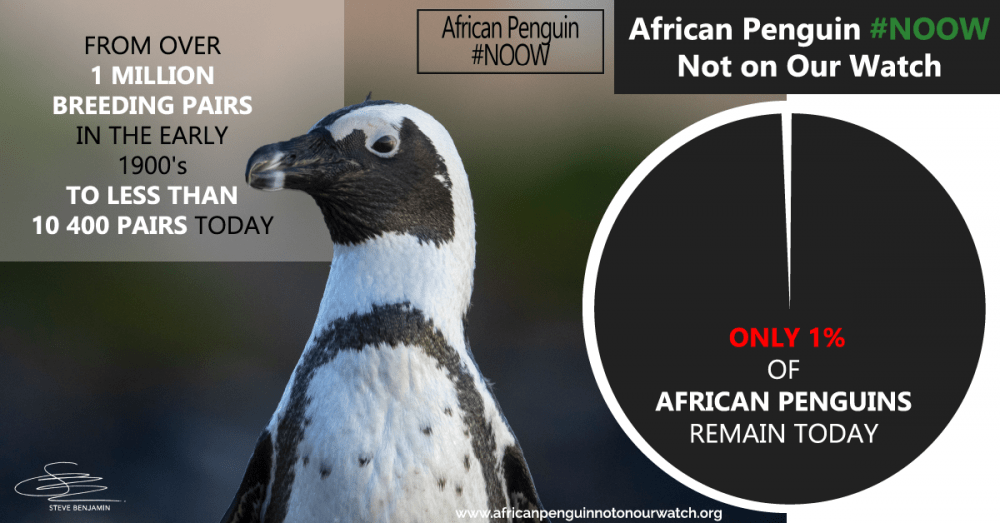

In the early 1900s, there were more than a million breeding pairs of African penguins on the various islands surrounding South Africa and Namibia but their numbers have plunged to fewer than 10 400 breeding pairs.

The two new ambassadors highlighted the threats facing the charismatic endangered seabirds — and the opportunities to prevent their extinction.

The campaign’s goal is to create a movement and raise awareness about the need for urgent action to reverse the decline of the African penguin population in the wild.

“We started the campaign because we said it’s going to take a collective effort to ensure their survival,” said Mann. “We feel that their extinction simply cannot be allowed to happen.”

Mann, who is the president of the International Zoo Educators Association and the executive of strategic projects at the Two Oceans Aquarium Foundation, said: “We’re down to about 1% of the original number of African penguins. If we continue at this rate of decline by 2035, it’s estimated that the African penguin will be functionally extinct, which means there simply won’t be enough of them to keep the species going.”

#NotOnOurWatch youth ambassador, Sophumelela Qoma.

#NotOnOurWatch youth ambassador, Sophumelela Qoma.

‘Working together’

“Sometimes problems seem insurmountable, but I’ve learnt that nothing’s impossible,” said Qoma, who comes from Ngqushwa in the Eastern Cape and is an advocate for marine conservation.

She earned a diploma in nature conservation from Nelson Mandela University and is now the co-owner of the Shark Research Unit, founder of an ocean investment trust in Mossel Bay and a key representative for five conservation programmes.

After completing high school, she faced a three-year hiatus from furthering her education because of circumstances beyond her control. During this period, she battled mental and emotional struggles.

“But, with self-discovery, clear goals, guidance, embracing change and learning continuously, I found a vision that was bigger than myself, and it propelled me forward. That’s why I believe that if we work together with passion and determination, we can save the very special African penguin from extinction,” she said.

Keira attends school in La Lucia, KwaZulu-Natal, and told the webinar of how her love for the ocean was nurtured by her grandfather, who has a passion for underwater photography and fish identification. Her dad was a South African surfer in his youth and involved in lifesaving.

In April last year, she completed the Robben Island swim — 7.5km in 10.5°C water — and raised R25 000 for the Turtle Conservation Centre at the Two Oceans Aquarium.

In August, Keira completed a 46km paddle from Salmon Bay in Ballito to uShaka pier in Durban on a prone board, which is paddled by hand. It took more than seven hours but she has raised R43 800 so far for the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Seabirds (Sanccob), which rescues and rehabilitates African penguins. Her target is to raise R50 000.

“It will help, but to stop their extinction, people around the world will need to care enough to get involved and raise awareness and make sure that authorities step in to protect the species from all of the threats,” she said. “As young people that’s the opportunity we have – we can save the African penguin and if we can do that, we can save the ocean.’’

Major threats

African penguins are faced with multiple pressures that are cumulatively contributing to their decline. Historically, egg-harvesting and guano collection caused their colonies to shrink.

Mann explained how, in the early part of the 1900s, the removal of guano led to the first rapid decline. Over the hundreds of thousands of years that the seabirds had lived on islands, they built up huge mounds of penguin poo, which they used to make their nests. “It was beautifully temperature controlled and just right for the hatching, the growing up of the little baby penguins.”

Guano is a good fertiliser that was called white gold “so, slowly over many years that there was guano harvesting, we removed all of the habitat of the penguins in which to make their nests.”

People also consumed penguin eggs. “There were millions of them so people didn’t think it was a problem,” said Mann. “In fact, African penguin eggs were actually served on the Titanic.”

Their more recent decline has been attributed to food shortages caused by shifts in the distributions of their prey species — anchovies and sardines — and direct competition with fisheries for food.

The destruction of the African penguin’s nesting habitat is also of concern.

Another threat is the expansion of harbours and an increase in ship traffic. The ship-to-ship bunkering that enables vessels to refuel out at sea increases the risks of oil spills. This has started in Algoa Bay, home to some large penguin colonies, and is planned to expand to the West Coast.

Out of sight, out of mind

Mann said: “One of the biggest challenges we face with the ocean is it’s out of sight and out of mind so we’ve got this blue blanket that covers our ocean but nobody really knows what goes on underneath. It’s invisible and it’s really up to each and every one of us to reveal and show what’s happening in the ocean.”

She said caring for the ocean is caring for people.

“Every second breath we take comes from the ocean. Ocean health is completely linked to human health. If the ocean dies, we die; it’s as simple as that. That’s why I think the penguin is such an icon for conservation, because it’s visible, it’s easy to see and tell us what’s going on in the ocean. We just simply have to look after this species.”

The #NotOnOurWatch campaign’s worldwide waddle on 14 October 2023 has been endorsed by the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development as a Decade Activity.