Aubrey Keirnan. (Supplied)

“Bird brain” is often hurled at someone as an insult, but scientists have discovered that the brains of birds are so large that they are “practically a braincase with a beak”.

By looking inside birds’ heads, in the largest study of its kind covering 136 species, the team of researchers in Australia and Canada have proven that “bird brain” is a misnomer.

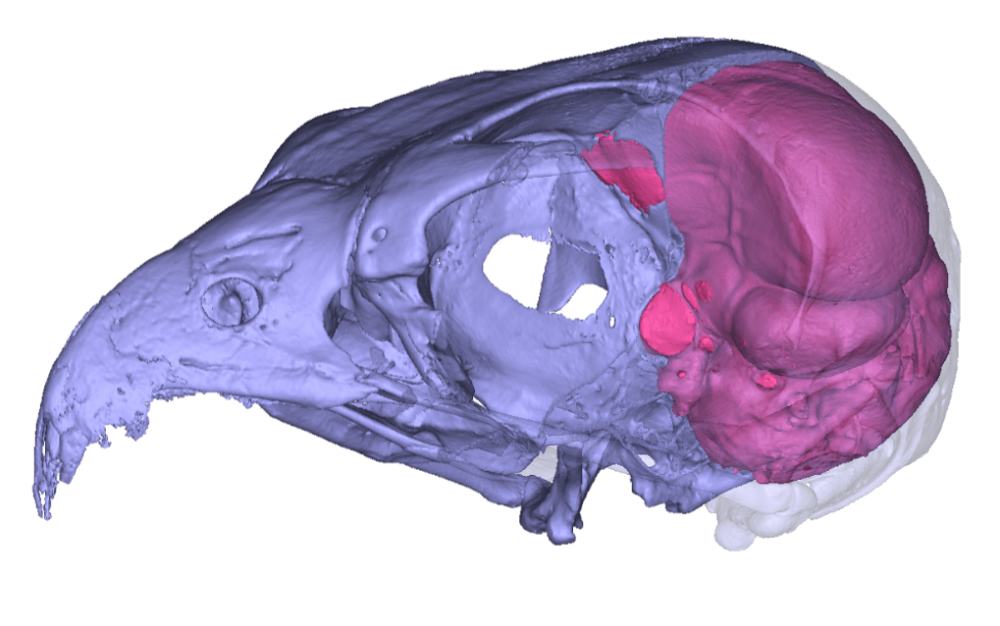

Evolutionary biologists at Flinders University in South Australia and neuroscience researchers at the University of Lethbridge in Canada joined forces to explore a new approach to recreating the brain structure of extinct and living birds by making digital “endocasts” from the area inside a bird skeleton’s empty cranial space.

Their study, published in the journal, Biology Letters, found that museum skulls of long-dead birds can provide surprisingly detailed information on a species’ brain, including the size of the birds’ main computation centres for smartness and nimbleness.

The discovery was made possible by comparing historical microscopic sections of the brain with digital imprints of the bird’s inside braincase.

“This showed that the two correspond so closely that there is no need for the actual brain to estimate a bird’s brain proportions,” Aubrey Keirnan, the study’s lead author and a PhD student at Flinders University, said in a statement.

“While ‘bird brain’ is often used as an insult, the brains of birds are so large that they are practically a braincase with a beak,” she said. “We decided to test if this also means that the brain’s imprint on the skull reflects the proportions of two crucial parts of the actual brain.”

The team scanned the skulls of the 136 bird species for which they also had microscopic brain sections or literature data. This allowed them to determine if the volume of two crucial brain parts — the forebrain and the cerebellum — corresponds with the surface areas of the endocasts.

What surprised the researchers was the tight match between the “real” and the “digital brain” volumes.

The senior co-author of the study, Vera Weisbecker, said they used computed microtomography to scan the bird skulls.

“This allows us to digitally fill the brain cavity to get the brain’s imprint, also called an ‘endocast’,” said Weisbecker, an associate professor from Flinders University.

“The correlations are nearly 1:1, which we did not expect. But this is excellent news because it allows us to gather insight into the neuroanatomy of elusive, rare and even extinct species without ever even seeing their brains.”

Advanced digital technologies are providing ever-improving access to some of the oldest puzzles in animal diversity, Weisbecker added.

“The great thing about digital endocasts is that they are non-destructive. In the old days, people needed to pour liquid latex into a brain case, wait for it to set, and then break the skull to get the endocast.

Using non-destructive scanning not only allows researchers to create endocasts from the rarest of birds; it also produces digital files of the skulls and endocasts that can be shared with scientists and the public.

Andrew Iwaniuk, of the University of Lethbridge, who co-led the study, said its findings provide support for existing research by other scientists, including for critically endangered modern birds or perhaps even extinct species.

But how well the data can be applied to dinosaurs, which are birds’ closest extinct relatives, is unknown. “For example, crocodiles are the closest living relatives of birds, but their brains look nothing like that of a bird — and their brains do not fill the braincase enough to be as informative,” said Keirnan.