Called the German-Namibian War by the descendants of the Ovaherero and Nama, the peoples killed for resisting German rule, the extermination strategy (which also affected the Damara and San) had lasting demographic and socioeconomic impacts, and left festering wounds.

(Photo by Fotografisches Atelier Ullstein/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

The Blue Book: a chronicle of crimes

When Major Thomas Leslie O’Reilly received the assignment from the Union of South Africa to gather evidence of the so-called natives’ “anxiety to live under British rule”, most likely one of his first candidates to interview was Chief Hosea Kutako. Chief Kutako (1870-1970), would have been about halfway through his 100 year-long life when he contributed to what would become the Blue Book.

At the time of his birth, the Herero were enjoying their last great glorious age of prosperity. “It is impossible to estimate the Hereros’ wealth even approximately,” writes an emissary from the British government in 1870. “The poorest families in a tribe possess something, three or four cows, a few oxen, 20 or 30 sheep,” while chiefs could possess “up to 25 000 head of cattle”. “A proud liberty-loving race, jealously guarding their independence, and with very strong family ties,” is how one put it; “an aristocratic tribe,” said another.

By the time Hosea Kutako gave evidence as one of 75 eye witnesses of Imperial Germany’s military project of racial extermination under the command of General von Trotha from 1904-1907, 80 percent (around 65 000-70 000 people) of the Herero and half the Nama population (around 10 000 people) had been killed, raped, and driven to death by flight into the desert, starvation and exhaustion.

During the war, Kutako smuggled Chief Samuel Maherero across the border into Botswana. He pledged to safeguard the Hereros who remained in Namibia. Maherero and the survivors were given shelter by Botswana’s regent, Tshekedi Khama. Years later, the regent remembered “them arriving from across the desert and my mother being deeply distressed because of their utterly starving condition, barely able to crawl”.

Kutako’s testimony reads, “We were crushed and well-nigh exterminated by the Germans in the rising… All our cattle were lost and all other possessions such as wagons and sheep. At first the Germans took prisoners, but when General von Trotha took command no prisoners were taken. General von Trotha said, “No one is to live; men, women and children must all die.”

“I believe they must be destroyed as a nation,” he said.

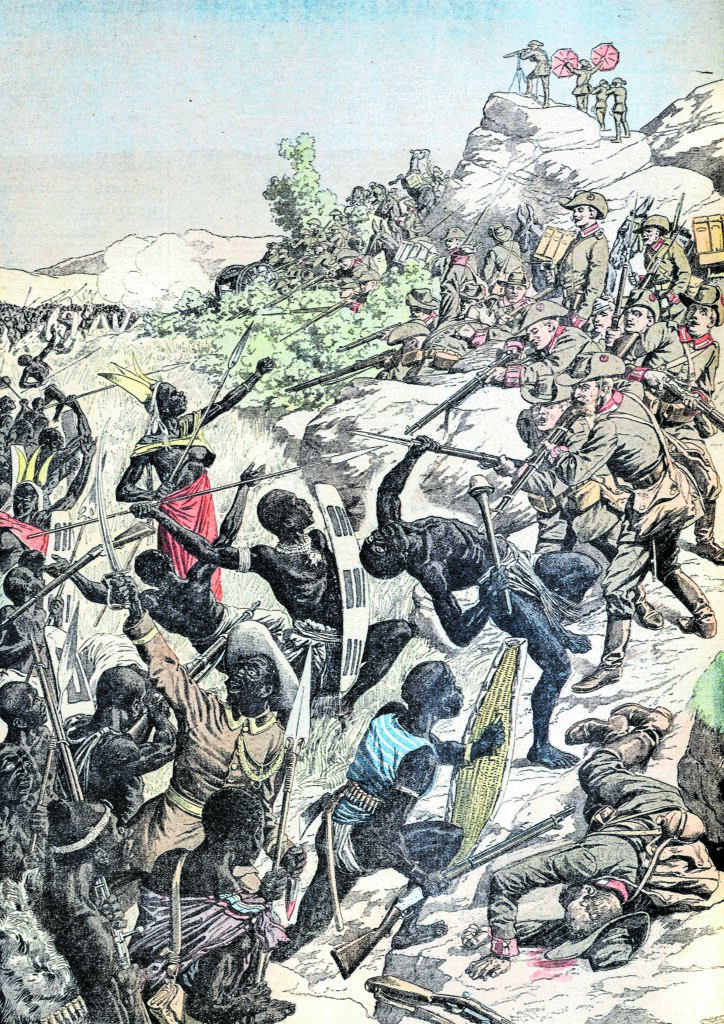

Battle Between Herero Warriors & German Colonials or Colonists Windhoek Namibia (Feb 1904) (Photo by Chris Hellier/Corbis via Getty Images)

Battle Between Herero Warriors & German Colonials or Colonists Windhoek Namibia (Feb 1904) (Photo by Chris Hellier/Corbis via Getty Images)

Kutako’s memory of the concentration camps were equally horrific – Herero rounded up by missionaries, trapped in churches and killed by German forces. Of the 16 000 that remained, 14 000 were forced into concentration camps where many more died under the unbounded cruelty of Imperial Germany.

“The people died there like flies that had been poisoned… The little children and the old people died first, and then the women and the weaker men. No day passed without many deaths. We begged and prayed and appealed for leave to go back to our own country, which is warmer, but the Germans refused. Those men who were fit had to work during the day in the harbour and railway depots. The younger women were selected by the soldiers and taken to their camps as concubines.” So Samuel Kariko says in Words Cannot be Found: German Colonial Rule in Namibia: An Annotated Reprint of the 1918 Blue Book

Prefiguring the horrors of World War II and apartheid South Africa, Canon Collins scholar Pedzisai Maedza shows in his PhD thesis exploring memory of the genocide that there were even human experiments in the camps for the purpose of eugenics research.

By 1907, German historians claimed that the Herero people had ceased to exist as a tribe. Their land was expropriated, and they were banned from cattle-raising and traditional forms of organisation. “Our cattle were appropriated at such a rate,” Kutako says, “that we felt it was intended to reduce us to pauperism.”

“It would be a sign of weakness, for which we would have to pay dearly, if we allowed the present opportunity of declaring all native lands to be Crown territory to slip by,” said the Imperial Colonial Office (19XX; Totten et al., 2004, p. 31 in Maedza).

At the outbreak of the First World War, South African forces, under British command, invaded German South West Africa and successfully defeated the German army. Namibia fell under South African administration. Now at the end of the war, with the fate of Germany’s colonies undecided, a decision was taken to compile evidence that would convince all the Allied forces that Germany should not retain control over its colonial territories, but that South Africa should be given the mandate to govern until the people of Namibia were fit to govern themselves.

Major O’Reilly gathered evidence of this from the Nama and Herero themselves and combined it with documentary evidence from German and British sources. It was published into the so-called Blue Book, an official document, in 1918. Fit for purpose, the Blue Book achieved its goal and Namibia was placed under the administrative jurisdiction of the Union of South Africa by the League of Nations, thanks in great part to the presence of General Jan Smuts on the Imperial War Cabinet. One wonders if the League of Nations was aware of South Africa’s expressed ambition since the 1900s to incorporate Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland and become a regional power?

South Africa enters the fray

The Blue Book was not the first time South Africa and Britain had been made aware of the atrocities of Imperial Germany. Detailed eye-witness accounts had been reported in the Cape Argus in September 1905. Reports were confirmed from more official sources, including the British Magistrate of Walvis Bay (Walvis Bay had been annexed by the British before the Germans arrived), British Intelligence and the Foreign Office. The response from London was that Britain had promised Germany not to get involved. “It won’t be easy to tell a great military power that its troops wage war like barbarians,” said the foreign minister, Lord Rosebery.

And so it was, until the question of what to do with Germany’s colonies after the war. In the Blue Book, the world now has a body of evidence that captures the testimony of African people during colonialism. This is very rare indeed. Nobody likes to talk about their trauma, but Hosea Kutako and others relived theirs in the hope of freedom, which they were told was within their grasp. Lord Buxton, the governor general of South Africa, in 1915, promised in person to “the natives” that their freedom, land and cattle would be returned to them.

With South West Africa in its grasp, South Africa now set upon inviting poor white Afrikaner communities to settle there. Courted with the offer of land, dams and loans, they responded enthusiastically, and between 1920 and 1925, South West Africa’s white population doubled.

In 1926, the first motion and first official act of the new all-white legislative assembly for South West Africa was to destroy all copies of the Blue Book and remove it from public memory.

The book had served its purpose to singe the conscience of the world with the profound suffering and loss of African Namibians for South African self-interest.

A new purpose had emerged, one whose only obstacle was the Blue Book itself, for it had become a source of deep offence to the local German community. In the words of General Smuts, “in my opinion the future of South West lies in cooperation between the old German community and the new Union community that was settling her.” (In Words Cannot Be Found).

The birth rate among the Herero fell so low after the war that it gave rise to a concern that the Herero were committing racial suicide. South Africa even went so far as to send a doctor to investigate the matter in 1920.

But contrary to the expectation that the Herero had become psychologically unfit, the interbellum period between the two world wars tells a remarkable story of Herero reconstruction in the face of South Africa’s vice grip. In the brief moments between Germany’s exit and South Africa’s entrance, small settlements of Herero began to appear on deserted farms, then German-occupied ones. Families began to return from their exile in Botswana. They began to accumulate stock. They were reclaiming their place and their identity. But they wanted to be together.

In 1919, Herero representatives sent a message to the governor general, Lord Buxton: “We want a piece of land where we can live as a nation and where our families can grow into a nation… We have been captives long enough, we want to be free.”

Land was not restored. It was further expropriated. In 1923, a proclamation allocated two-million out of 57-million hectares of the most barren and remote land in Namibia to African Namibians, who comprised 90% of the population.

South Africa made it illegal for an African to be found off the reserve for any reason other than labour. The Vagrancy Law would force any “idle or vagrant person” to work for a court-appointed employer in conditions and for wages they had no say in.

The African Namibians’ hope of independence and restoration vanished in a new dawn that instead greeted them with military suppression, bombings and arrests.

Hosea Kutako hired a lawyer and wrote petitions to administrators. He would continue to make legal recourse and petition the administration in the years to come as laws became more hostile, shrinking the space in which the Herero could live dignified lives. A skilful politician and negotiator, Kutako was able to continually enlarge the reserves, improve their grazing areas and represent the needs and complaints of the Herero before the colonial authorities.

The Blue Book and the idea of international accountability

By 1935, it was reported to the legislative assembly that “all known copies of the Blue Book” had been destroyed. The Blue Book achieved something that would be important for minority and colonised people across the world in the decades to come: the idea that there should be international accountability for how global powers treated minorities, nations and tribes. Even though the principle was only applied to the Central Powers at that time, it was a small but important step on an upward path that would include independence for colonial territories.

But that is leaping ahead. After World War II, South Africa increasingly imposed its racial policies “more ruthlessly and brutally in Namibia than in South Africa itself”, according to historian Chris Saunders. As it became clear that Namibia had great mineral wealth, South Africa became determined to incorporate the country.

It conducted a spurious referendum that falsely reported Namibian tribes gave their consent to incorporation. They told the UN that African Namibians were enjoying the schools and other amenities that South Africa had generously bestowed. The fact was that by 1940, the South African regime had only built two schools for African Namibians, and they only went up to Standard 3 (now Grade 5).

It was then – for its story was far from over – that the Blue Book once again came into play. The Herero chiefs put it into the hands of an English priest who had a reputation for trouble-making – the Reverend Michael Scott. In South Africa, after drawing international media attention to the diverse ways in which the South African government was dehumanising and depriving black South Africans, Rev. Scott had developed the reputation for being “the straw at which desperate people clutched”. He would dedicate the rest of his life to prevailing upon, in his words, “the conscience of the world” on the matter of Namibia.

Unfortunately for the ambitions of the Union of South Africa, his efforts would not return void.

This article is the first in a two-part series and was developed as part of the blog project “Troubling Power: Stories and ideas for a more just and open southern Africa”, which marks the 40th anniversary of the Canon Collins Educational and Legal Assistance Trust.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.