Analyses of racialised disparities in both labour and product markets illustrate the need for strengthened economic redress. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G

COMMENT

I previously wrote about how post-pandemic infrastructure stimulus spending could take us even further backwards because of the way “local content” is structured. We are getting closer to the point where we need to think about this, with the onset of level two.

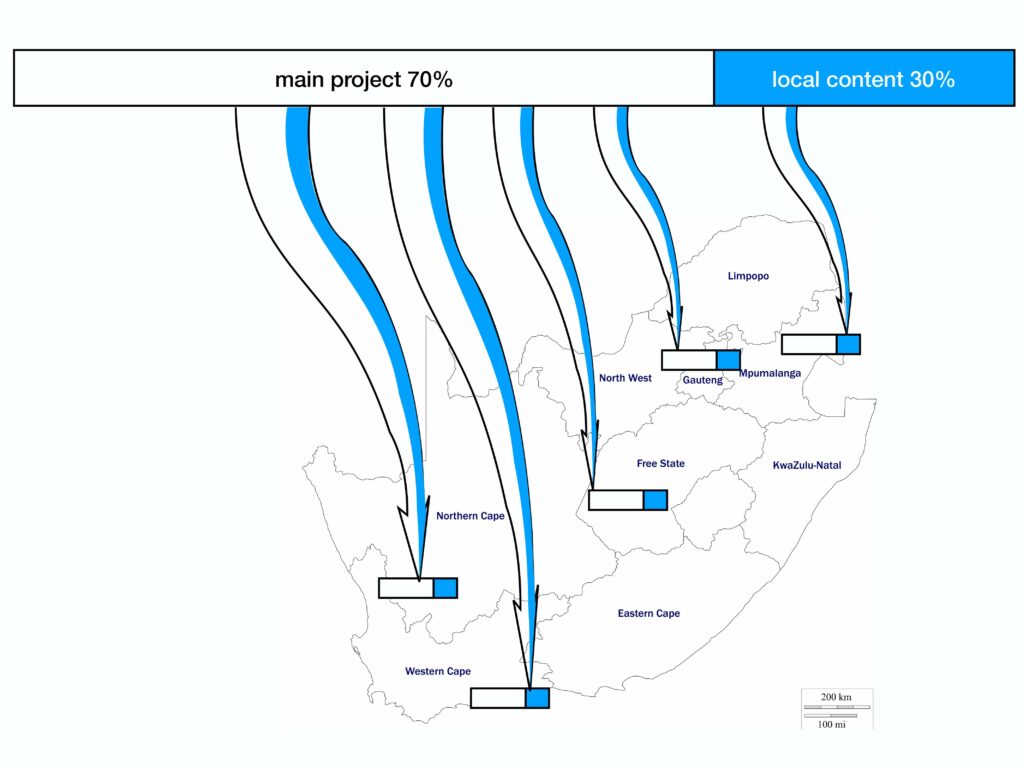

Government policy for major tenders requires that 30% be awarded to local contractors to promote local skills development and economic opportunity. This picture illustrates how major infrastructure projects are split into 70% for the main contract and 30% “local content”, which is meant to stimulate small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) and broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE). I explained in the previous article how this approach feeds into patronage and inventivises failure.

Maps source.

This time, I explain in more detail an alternative that is cost-neutral, does not incentivise failure and is much more likely to promote employment and more broadly reduced inequality.

But first, I need to explain why the existing approach is a bad idea not only because of patronage.

Since 1994, the ANC government has been quick to snatch at a bargain like two for the price of one (buy all these arms from us and we will build factories and create jobs) or ever three for the price of one (while building infrastructure, we will also promote SMMEs and B-BBEE).

The problem with this approach is that it mixes objectives and in the worst case you end up with zero for the price of three – as happens because patronage is an incentive to ensure that major projects fail.

As noted in my previous article, the 30% local content slice greases patronage networks and failure of the main project only makes it all happen again. However, this is not sustainable as collapsing infrastructure erodes the tax base and, eventually, the entire social contract. Government that cannot serve basic needs becomes pointless.

Big business is fundamentally different

Another problem is the idea of big business and government being the engine for growing small business. Large organisations operate in a fundamentally different way to small ones – they are highly bureaucratic and process-driven. Small organisations are more informal and can operate at the whim of the proprietor: they do not have a supplier database, their audit requirements are simple and they cannot afford to specialise labour to the same degree. Often, in a very small business, the accountant, CEO and head of sales and marketing are the same person. For small businesses – especially new start ups – there is a huge learning curve for subcontracting to a large organisation.

The large organisation has the headache of dealing with numerous small players who are not consistent with each other or even themselves. The simplest way to do this is for the large organisation to treat “local content“ as a tick-the-box exercise and regard the money spent as a form of tax rather than a productive part of the project.

The small subcontractors therefore are not really selling a service and do not acquire the skills needed to sell on a competitive basis. So when the big contact goes away, so does their business. Not only does that lock in patronage but it also subverts the purpose of “local content”: building sustainable small enterprises that financially empower the previously marginalised.

The problem with reforming such a system is that too many beneficiaries of the existing format have reason to resist doing away with it. That is why I propose altering the way major projects are funded so that the 30% local content is still there but no longer embedded in a major infrastructure project – particularly not one that is essential, ie, one that has to be completed to enable other economic activity.

Separate budgets

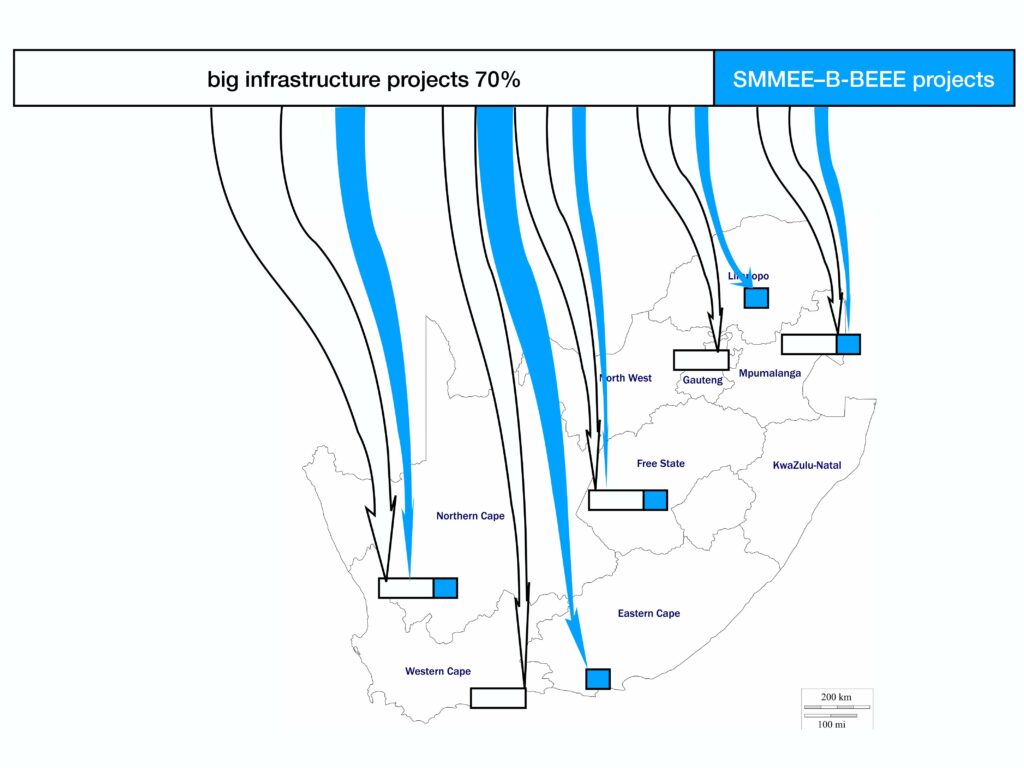

Take a look at the second picture (a fictional scenario to illustrate the principle). The national budget is split the same way. But the 70% that goes to the main contractor is now the only budget for that project and the 30% local content is a totally separate budget.

This has three benefits. First, essential infrastructure projects are decoupled from local patronage networks. Second, big contractors can stick to what they are good at – complex, process-oriented projects. Emerging small businesses are better placed to develop skills that transfer to other domains. Third, the 30% local content slice no longer has to be spent in the same place as a major infrastructure project. As illustrated, Western Cape and Gauteng each have a major infrastructure project without any “local content” whereas Eastern Cape and Limpopo do not have a major project but do have “local content”.

Even patronage players have reason to prefer this system: they can focus on bids for “local content” projects and keep out of large infrastructure projects where they are more likely to be out of their depth. And if essential infrastructure is built, there will be more local economic activity and more money for them.

Up to now, South Africa has done a terrible job of reducing inequality and SMME and B-BBEE policies have benefited far too few people.

Post-pandemic infrastructure stimulus spending is a huge opportunity to get this right. If we continue to incentivise failure, we risk going backwards at a rapid rate. Much criticism of patronage, corruption and general government failure stops at moral outrage. That is well and good but moral outrage does not solve the problem. It’s time we started talking solutions. That is the debate I aim to open up.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.