Residents are dispersed by the South African Police Service during a demonstration in Eldorado Park, Johannesburg, on August 27, 2020. (Photo by Ali Greeff/AFP)

Our policing crisis runs deep, it runs wide in the number of issues it contains and their origins, but one thing is clear: it starts at the very top.

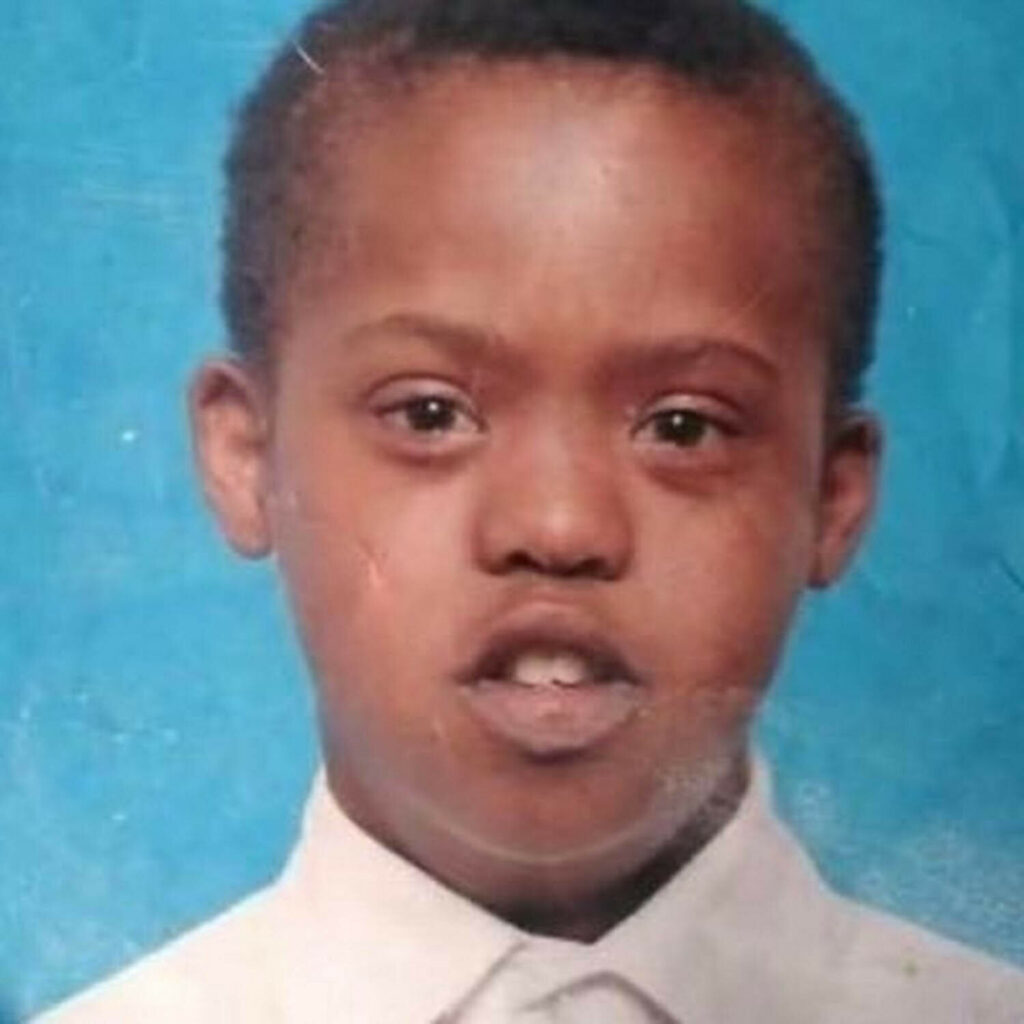

The killing of Nathaniel Julies outside his home in Eldorado Park on August 26, allegedly by a police officer who shot the teenager in the head and chest, has sparked anger in the country. Not only was the teenager unarmed, he was also living with Down syndrome. Because his ability to communicate was limited, he was unable to respond to officers’ questions.

Nathaniel Julies

Nathaniel JuliesThis is all relevant to his death because the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the premier of Gauteng, David Makhura, have since claimed that Julius was killed during a confrontation between police officers and gang members. It is true that gang violence is rife in Eldorado Park, a suburb south of Johannesburg, but this official explanation is in direct contradiction to witness accounts of the incident.

Neighbours say that Julies had gone to a shop to buy food and that there was no gang shooting or violent activity at the time he was shot. Furthermore, witnesses allege that the police officers bundled Julies into the back of their van and took him to Baragwanath Hospital where he died. Makhura has asked for patience from Eldorado Park residents while the police watchdog and oversight authority, the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (Ipid), investigates the incident.

The explanation from police officials and Makhura mentions no arrests from the confrontation between police and Julies, or any other gang member(s) as alleged. There are also no arrests mentioned from any preceding or subsequent police action immediately after the shooting.

What we do know for sure is that the SAPS kills three times more people per capita than police in the United States do.

According to the Washington Post, which collected this data over several years, the police across the US killed 990 people in 2018. According to the Ipid’s own annual statistics, (table 4, page 42) SAPS officers killed 538 people in the 2017-2018 reporting year, and 440 people in the 2018-2019 reporting year.

South Africa’s population in 2018 was 57.78-million people and the US population in 2018 was 327.2-million people.

Although it is true that it is dangerous to be a police officer in South Africa, it is also true that many police officers are killed off duty and not while performing their duties: in the 2016-2017 reporting year, 28 of the 85 police officers who died that year were on duty. Compared with our neighbours, Namibia and Botswana — similar African countries with stable democracies — our incidents of police violence are alarmingly high.

South Africa is a violent country with high levels of domestic violence, gender-based violence, gun violence, gang violence and deaths at the hands of the police. All of these factors have come together in the death of Julies, but it is not the first nor the last time this will happen. The police must be held accountable when they harm, seriously injure or cause the deaths of innocent people in the course of their work.

The agency charged with this responsibility, Ipid, is critically underfunded, understaffed and, importantly, it reports to the political head of the SAPS. These factors make the process of achieving justice for victims of police violence endlessly difficult, if not impossible. This needs to change and citizens need to demand this change.

The political leadership of the SAPS has repeatedly excused and even encouraged police violence. Remember national police commissioner Riah Phiyega congratulating officers for crushing the Marikana strike at Marikana exactly one day after the August 16 2012 massacre in which 34 miners died: “[Your] actions represent the best of responsible policing”. Remember when Bheki Cele was the police minister in 2009 and instructed police officers to “shoot to kill” and “worry later”. Cele is minister of police again today.

The police service cannot disregard the law and the basic human rights of people, including suspected criminals. This must start with us refusing to allow politicians and police leadership to protect violent police officers.

Police brutality and violence is systemic and has been institutionalised from the very origins of the colonial and apartheid-era South African Police (SAP); we must acknowledge this in every conversation about policing in our country.

The media on the scene at protests in Eldorado Park should continue to gather eyewitness accounts, as well as first-hand accounts of police action during them. People living in this country need to pay attention to the various accounts of the incident while critically analysing the narratives that are forming around the protests, in light of the community’s long history of violence.

For us to fix the policing crisis in this country, we must admit that the institution and system is broken. It is so broken that innocent children are caught in the crossfire of both violent crime and violent police action. It is so broken that those in low-income areas bear the brunt of both poverty and crime and of police brutality and violence. It is so broken that the political leadership of our police service would rather protect violent police officers and defer to investigating authorities they know are overwhelmed and underfunded, instead of taking responsibility for the pattern of behaviour among police officers that has now led to the death of Nathaniel Julius.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.