Bolivian president Luis Arce waves to supporters during the closing rally of his campaign in El Alto, Bolivia on October 14, 2020. (Aizar Raldes/AFP)

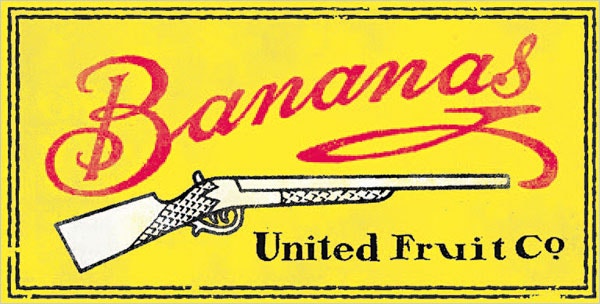

Like so many commodities, the import of bananas began with colonialism. After that came the conglomerates who soon replaced states in the role of coloniser.

United Fruit began life in the 1870s when Minor Cooper Keith, a wealthy young New Yorker, started growing bananas alongside a railway line he was building in Costa Rica.

It would go on to become one of the first truly multinational modern corporations, spreading the spirit of liberal capitalism by dominating business and politics in Central America.

In addition to harvesting the region’s fruit, the company wielded formidable influence over small nations, which were often ruled by corrupt dictatorships.

United Fruit gave the world not just bananas, but also “banana republics”.

Initially, the Honduran government blocked United Fruit from entering the country. But in 1911, one of United Fruit’s business partners financed and organised its government’s overthrow.

It marked the beginning of a history of “regime changes” in the interests of the banana trade.

In 1954, United Fruit devised a plan to get rid of the Guatemalan government. The democratically elected government had taken some of United Fruit’s large areas of unused land to give to peasant farmers.

The company called up newspaper contacts who might be amenable to its view, sending journalists on “fact-finding” jaunts to Central America and, in particular, Guatemala, where they made up stories of gunfire and bombs.

In their reporting, the country became a place in the grip of “communist terror” .

Further south, it has been quite an eventful year in Bolivia. Luis Arce — successor and ally of Evo Morales — emerged victorious in the country’s elections last week, with his rival, the United States-backed President Jeanine Áñez, forced to concede defeat. The defining election comes a year after Morales was forced from power and the interim government of Áñez installed.

Morales, a hugely popular figure through much of his tenure, had attempted through various avenues to pursue a fourth presidential term before the military had nudged him into resigning.

His Movement for Socialism (MAS) party unequivocally viewed the ousting as a coup.

Given the American penchant for putting the boot in, its potential involvement in the transition of power has generated more than just whispers.

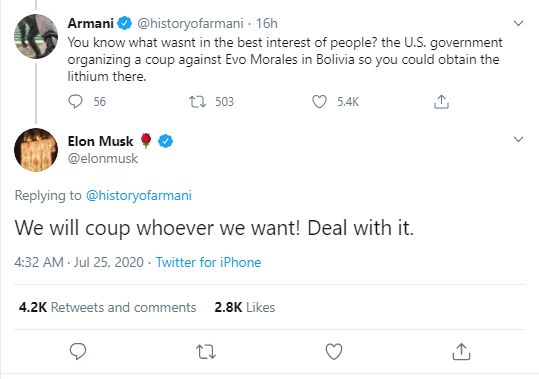

One man not doing himself or his adopted country any favours in silencing those suggestions, is tech billionaire and former South African Elon Musk. In response to a suggestion that the US government orchestrated a coup in Bolivia so as to prevent the nationalisation of lithium — which Tesla uses to power its electric vehicles — Musk tweeted: “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.”

Usually quite vocal about violent regime change, Washington think tanks and prominent voices in the media were quick to defend the government, citing Morales’s alleged wrongdoing.

In a year now infamous for the in-tandem spread of far-right authoritarianism and a deadly disease, it is gratifying to watch another Latin American country take back its power.

It started with anger over higher subway prices, but a growing wave of protests — referred to as el estallido (the explosion) — followed, and now people in Chile have voted overwhelmingly to throw out their country’s Pinochet-era constitution and create a new document under which to live.

Arce’s electoral win and the Chilean people’s “do-over” are a stinging rebuke to all of the nonsense that so many pundits spouted to excuse Morales’s removal or the heavy handedness of Chile’s security forces.

The credit for MAS’s resounding victory must go to Bolivia’s social movements, historically some of the strongest in Latin America.

As Arce proclaimed in his first speech following the election: “We have recovered democracy,” this is a massive triumph for democracy in Bolivia and Chile. Liberal capitalism and neocolonialism are not democracy.

Kiri Rupiah & Luke Feltham write The Ampersand newsletter for subscribers. Sign up now for the best local and international journalism handpicked and in your inbox from Tuesday to Friday.