The video on social media of white men trying to throttle and drown black boys in a pool at the Maselspoort resort in the Free State on Christmas Day. Photo: Supplied

The video on social media of white men trying to throttle and drown black boys in a pool at the Maselspoort resort in the Free State on Christmas Day is an indication that the apartheid past of racial hate and internalised superiority complexes continues today.

President Cyril Ramaphosa condemned the ordeal of the boys as “cruel acts of racism and humiliation” at the hands of “old, white men”.

Just a month prior to this, Belinda Magor launched a racist rant on a voice note against banning pit bulls, calling black men to be killed and for black women’s uteruses to be removed because they were, in her view, worse than pit bulls.

The apartheid system ended in 1994 but the racist mindsets it bred clearly remain.

Internalised racist complexes were acted out externally through racially charged violence. To borrow from the decolonisation discourse of Professor Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s best-known work, Decolonising the Mind, which discusses the nexus between language and colonisation and calls for decolonising the African mind, South Africans need to decolonise their minds if we are to truly leave our racist past behind.

He also notes that colonising African minds was a key strategy of colonisers, highlighting that language was used as a weapon — imposing the coloniser’s language and forbidding colonised people’s native language.

Apartheid was a form of colonialism, according to the South African Communist Party (1965), because white nationalism was a unique form of colonialism where the colonial seat of government was inside South Africa and not in a parent country in Europe.

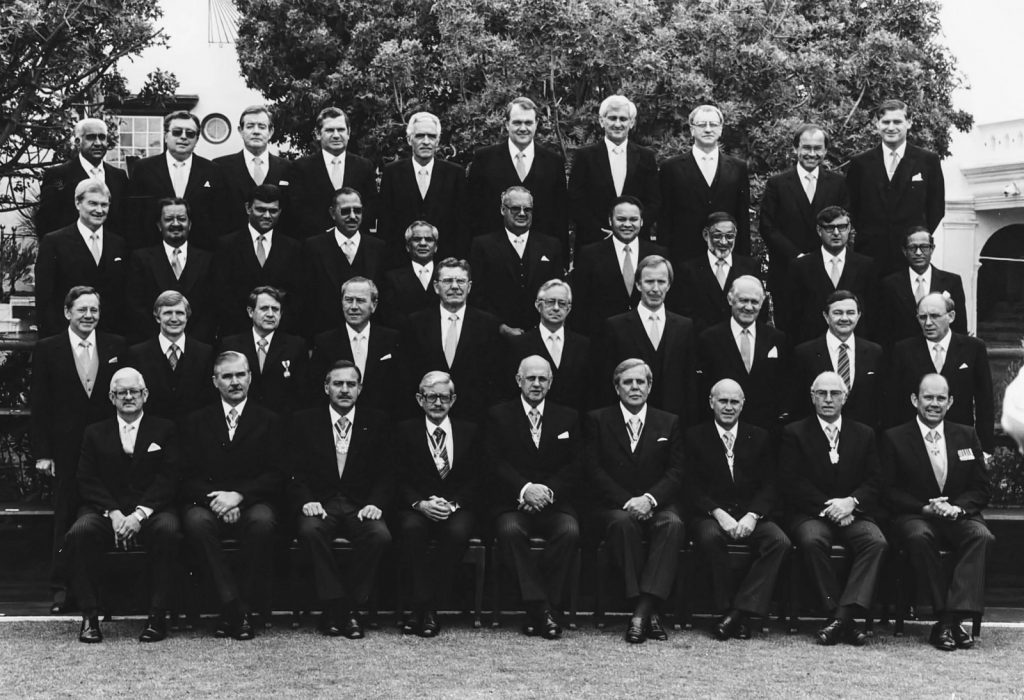

Apartheid Cabinet. Photo: Supplied

Apartheid Cabinet. Photo: SuppliedThe post-apartheid media has an important role to play in decolonising the South African mind. It was key to apartheid’s success by legitimising its white supremacy propaganda and therefore white people internalised superiority and black people internalised inferiority complexes.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1998) found: “During the years of apartheid, journalism was literally framed in black and white and played a role either as a vehicle for advocacy against the apartheid regime or as a subservient servant of the regime.”

Decoloniality identifies the continuance of colonial patterns of power after the end of colonial administration referred to as “coloniality”. The post-apartheid media reflects many “colonialities” despite the sovereign end of apartheid. We need to start with decolonising the post-apartheid media to decolonise racist mindsets and break the patterns of our past so that no black child will have to endure the trauma that those did at the Maselspoort resort or in any other space in the country.

The global “decolonial turn” has officially been upon us since the early 20th century. Prominent decolonial scholar Professor Nelson Maldanado-Torres said: “The decolonial turn does not refer to a single theoretical school, but rather points to a family of diverse positions that share a view of coloniality as a fundamental problem in the modern (as well as postmodern and information) age, and of decolonisation or decoloniality as a necessary task that remains unfinished.”

The events, moments and movements that lead to the solidification of the decolonial turn were the collapse of the European Age in World War I and the second wave of decolonisation in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean; the Bandung (Asian-African) conference in 1955; as well as movements that heightened perception of the linkages between colonialism, racism and other forms of dehumanisation in the 20th-century, and the formation of ethnic movements of empowerment and feminisms of colour, and the appearance of queer decolonial theorising (Maldanado-Torres).

Similarly, in South Africa the “decolonial turn” was symbolically ushered in through an event — the “fallist”student protests in 2015. On 9 March 2015, the #RhodesMustFall student movement began at the University of Cape Town, which questioned the imperial white supremacist legacy of Cecil Rhodes. It led to a wider national protest movement, #FeesMustFall, which advocated for free decolonised education.

But for the decolonial project to be meaningful in South Africa and other parts of the world that share similar forms of historical oppression and discrimination (the Global South locations), decolonisation is a process that must continuously develop after the fact of symbolic movements and events.

Despite the decolonial turn being upon the country since 2015, the post-apartheid media’s decolonial project is yet to take off despite numerous colonial legacies. Racist tropes of blackness appear in media content, media access and audience reflects inequalities. There is also white privilege in ownership patterns and board representation.

Studies have found hyper-negativity in the representations of blackness that are legacies of colonial and apartheid tropes of blackness namely: inherently violent; disposed to irrationality, criminality; primitive; sub-human; inferior; incompetent; corrupt; danger; “damned of the Earth” colonial subjects. These are reflected in the work of Sarah Chiumbu, Jane Duncan, myself, Dimitris Kitis and Rebecca Pointer.

William Gumede’s 2016 perspective captures the deep-seated nature of the legacies of apartheid: “The challenge for South Africa is how to overcome the legacy of deep-seated individual, institutional and everyday racism that persists long after official apartheid was scrapped from the statute books. It is often disguised in the supposedly ‘standard’ operating procedures, practices and behaviour of institutions and organisations which everyone has to follow — but which is skewed against blacks. Day-to-day casual racism, entrenched from the legacy of slavery, colonialism and apartheid still abounds. Blackness continues to be associated with negativity — crime, rape and failure.”

Franz Krüger, of the journalism department at the University of the Witwatersrand, found that the media landscape in South Africa reflects inequalities inherited from apartheid such as that wealthier and urban audiences have a wide choice of media while the rural and poor audience has restricted access. To take his findings further, these inequalities are racialised with white privilege still dominating the wealthier and urban groups, and the rural and poor consisting of the black majority. Hence, it can be deduced that there are a number of apartheid inequalities in audience access across the axis of region, class and therefore race.

Media ownership patterns and boards also presently exhibit white privilege. The Mail & Guardian reported in 2019 that the media is still run mostly by white people following its of analysis of ownership structures, demographics and funding models, notably “the boards of media houses comprise 41% white, 24% African, 17% coloured, 16% Indian and 2% of people from elsewhere”.

It is high time for the post-apartheid media to follow the decolonial turn. Maldanado-Torres captures the crux of the decolonial turn: “The decolonial turn is about making visible the invisible and about analysing the mechanisms that produce such invisibility or distorted visibility in light of a large stock of ideas that must necessarily include the critical reflections of the ‘invisible’ people themselves. Indeed, one must recognise their intellectual production as thinking not only as culture or ideology.”

At a proactive and practical level, the South African media can play a decolonial role which means striving to not only end the perpetuation of apartheid “colonialities” but also deliberately and vigorously work to ensure meaningful visibility of blackness in its content representations, access and audience, ownership, boards — that are a rupture from its racist past so as to change racist societal stereotypes.

This piece is based on a journal article, Media Decolonial Theory: Re-theorising and Rupturing Euro-American canons for South African media, forthcoming in the Communication journal.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.