Creativity is Lionel Messi’s imperceptible feint to the

left; it is Magnus Carlsen’s subtle pawn manoeuvring in

tight endgames. It is laced in Notorious BIG’s lyrics and

Mozart’s wordless symphonies. It is the invisible spirit

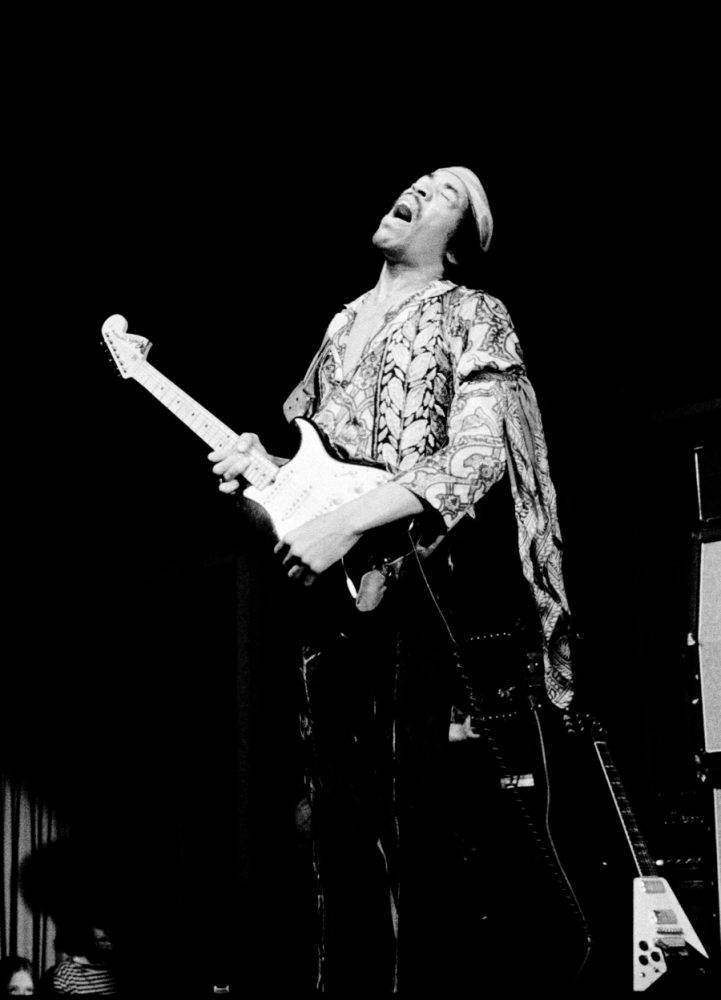

that erects our buildings and sews our clothes. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Comedian Bill Hicks once gave his audience an interesting proposition.

“If you don’t believe drugs do anything good for us, do me this favour will you,” he suggested after a bit about how peaceful the world would be if it were filled with pot smokers.

“Go home tonight, take all your albums and tapes, okay? And burn ’em. Cause you know what, the musicians who made all that great music … real fucking high.”

The implication he so eloquently articulated was that artists — some of the greatest — draw from psychoactive wells of inspiration.

It’s not a novel idea. The story of human history is that of a species that has revelled in attaining different states of consciousness, often in pursuit of unlocking mental pathways inaccessible in daily sobriety.

Or, in short, we become more creative when we’re high.

Marijuana, for its availability and perceived benignness, is the poster child for that idea.

But recent headlines would have us believe this is a badly mistaken idea.

“Sorry, weed probably does not make you more creative”, The Washington Post regrets to inform you.

“Cannabis use does not increase actual creativity but does increase how creative you think you are, study finds,” reports PsyPost.org, with ever so slight undertones of condescension.

“Weed might not make you creative after all,” notes Discover magazine.

The best headline, from Ceros.com, almost certainly came from someone who partakes themselves: “Will cannabis spark my creativity or blunt it?”

The first three articles are based on the same 2021 study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology by the University of Washington’s Yu Tse Heng, Christopher M Barnes and Kai Chi Yam, titled Cannabis Use Does Not Increase Actual Creativity but Biases Evaluations of Creativity.

The research begins with the premise that well-known figures, such as Lady Gaga and Steve Jobs, openly credited their indulgence for a boon in their creativity. But, through the course of their research, they found no evidence to support the idea.

This is by no means the first research into cannabis and creativity but might well come to be seen as seminal for two reasons. A: Thanks to weed’s new legality, researchers were able to reliably study more than 200 participants. B: The university’s communications team has evidently done a superb job in getting the study into the hands of multiple outlets.

At the time of writing it is these reports that shoot to the top of any Google search including both the words “cannabis” and “creativity”; as with anything, the algorithm’s priority will be the last word for many cursory searchers.

This is why it’s worth looking at the study again and asking if its findings have been adequately contextualised in the media.

It’s a question that resonates beyond this subject. Reporting on scientific research in traditional news publications often has a narrow scope to it. You could easily find headlines that praise the healing powers of cheese or swear to the fitness benefits of wine.

News editors in the internet age are always looking for the “quick hit” — something funded research is all too happy to oblige. And, in fairness to the underfunded and understaffed editor, the context they need is usually locked away behind paywalls.

It’s clear we’re less interested in working out how Jimi Hendrix wrote Purple Haze and instead want to know if there’s value in getting Jonah Hill stoned over a pool table in the hope of squeezing out a fresh stock tip.

The paper in question

The first thing to understand about the Washington study is communicated in its preamble. The paper launches off of the idea that many modern employees use cannabis to 1: alleviate stress, 2: improve concentration and 3: “facilitate creativity, defined as ‘the production of useful and novel ideas’. Many have the lay belief that using cannabis can increase creativity though evidence for this link is mixed.”

It is the latter suggestion that is being tested here.

While the authors do purport to examine creativity as a broad concept, it is reasonable to infer that a corporate lens is applied with an eye on corporate objectives. That’s only natural given the study specifically comes out of the university’s Foster School of Business.

The report says as much in its listed contributions: “Our work informs organisational policies on cannabis use and the debate on cannabis use legalisation by advancing knowledge on how cannabis use impacts work, specifically creativity outcomes.”

It’s clear we’re less interested in working out how Jimi Hendrix wrote Purple Haze than in knowing if there’s value in getting Jonah Hill stoned over a pool table in the hope of squeezing out a fresh stock tip.

The specific hypothesis the paper is testing is the belief that cannabis increases joviality, which indirectly increases creativity. Put more crudely, weed makes people happy; happy people are more likely to open their minds to more thought pathways.

To actually measure the output of creativity, the researchers used two methods. The first involved sending test kits to their participants’ homes. Instead of being supplied with weed, they were asked to smoke their own — the same weed they imbibe in their usual routine.

This is important because it sidesteps the moral issue of supplying substances to test subjects as well as preventing the exercise from being focused on one strain.

The study instructed that it should begin at least 12 hours after the last cannabis use and within 15 minutes after imbibing anew. Participants then took the alternative uses test.

Developed by JP Guilford in 1967, the test is widely used as a yardstick for someone’s ability to provide varied and divergent thinking (the creative process of exploring multiple solutions). Simply, the subject has to list as many uses they can think of in a time period for a common object — usually a brick.

Someone with a more staid personality might struggle after they run out of structures to build. But the creative, theoretically, will keep pumping out ideas as their mind travels from tyre stop to an effective way to mute a mother-in-law. (Both real responses.)

The second study was limited to signees who had full-time employment. After consuming cannabis, just as before: “Participants were instructed to imagine that they were working at a consulting firm and had been approached by a local music band, File Drawers, to help them generate ideas for increasing their revenues. They were told their goal was to generate as many creative ideas as possible in five minutes. Following which, they completed global and idea-level creativity self-ratings.”

The results of both studies culminated in the headlines we began with — weed does not increase creativity.

It did boost joviality — something no one would dispute — but the indirect effect was not to enhance creativity but rather evaluations of creativity, both of one’s own work and others.

Or as PsyPost put it, “Cannabis use does not increase actual creativity but does increase how creative you think you are.

People with a willingness to experiment with substances are similarly likely to have an openness towards toying with new ideas, a key asset of divergent thinking.

Hidden genius of creativity

“Some of the greatest blessings come by way of madness, indeed madness that is heaven-sent.” — Socrates in Phaedrus

In its end discussion, the paper notes that “motivation” was a difficult variable to control. As many pot smokers would tell you, anything considered work is usually the furthest thing from a buzzed mind.

This is important to understand because, subconsciously, a person considering uses for a brick might perceive the task to be sufficiently completed when their attention is drifting elsewhere.

Indeed the intuitive reaction here is to question whether the tasks in the studies approximate the type of creativity people who claim to be positively influenced by cannabis are referring to. And again, in fairness to the research, one of its stated objectives is to provide recommendations to places of work vis-à-vis their own incentives.

The natural follow-up is to ask to what extent, if any, the results here can be applied to broader conceptions of what it means to be creative.

But defining creativity is as craggy a rabbit hole as you could ever tumble into. How do we even begin to define a concept that we assign to so many facets of the human experience?

Creativity is Lionel Messi’s imperceptible feint to the left before he glides to the right; it is Magnus Carlsen’s subtle pawn manoeuvring in tight endgames. Creativity is laced in Notorious BIG’s lyrics and Mozart’s wordless sympathies. It is the invisible spirit that erects our buildings and sews our clothes.

Is it possible to define such a ubiquitous essence, let alone measure it?

Plato equated creativity to divine inspiration. In his dialogue Ion, his character Socrates argues that none of the epic poets are “masters of their subject”. They do not harness their ability or skill (techne) in their work but rather allow themselves to be possessed by a god or goddess — a muse. (“Inspired” directly translates to “filled with a spirit”.)

These poets, Plato says, are consumed by a divine madness. The word is not used with the mental health connotations that it is today but rather indicates the state the artist assumes that enables him to produce something beyond mortal capabilities. The Romans similarly crafted the Latin word genius to denote the guiding spirit that sits with a person from birth.

Steven Pressfield’s cult book The War of Art is based on the same premise. He describes the muse as a capricious spirit that must be courted with love and loyalty if the artist hopes to succeed in their work.

As in many Greek themes, we see a crossover into Norse mythology as well. Kvasir was born after two warring groups of gods spat into a vat as a sign of truce.

His intelligence was unrivalled and he duly travelled the world, spreading his knowledge.

But the dwarfs Fjalar and Galar captured him, killed him and drained his blood into a pot before mixing it with honey to make the Mead of Poetry. Anyone who drank it was imbued with a divine inspiration that produced the most glorious prose. (Notice how a digestible substance is the key to unlocking the Socratic madness.)

Aristotle, Plato’s student, had a far more pragmatic view of creativity. To him, the process was completely rational; one that could be honed and refined. Everything the brilliant poet does is logical and causal; her description of certain characters or their actions is deliberately engineered to invoke a desired reaction from her audience.

After the Renaissance, philosophical thought of creativity began to veer closer towards what many of us today conceive of it — not necessarily mythical, but mysterious.

Emmanuel Kant insisted the genius of a person can never be understood — not even by themselves — and regrettably can never be learned or taught. He also distinguished between genius and novelty: “There can be original nonsense.”

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, this idea that something must be both new and of value forms the basis of much of the perceptions of creativity in much of psychology. But definitions remain equivocal, while there is certainly no consensus on how to measure it.

The problem again is works of true creative genius are so perplexing. Sometimes we don’t even know we are staring at something truly remarkable until its mysteries and nuances unravel in our brains over time.

A braggadocious Kanye West once asked if he was too complex for Complex. You can decide for yourself the answer to that particular question but the sentiment is a common one. How many artists revile critics for the very reason that their sole purpose is to describe the inexpressible? To peel back the magician’s curtain, robbing the act of its magic.

American writer EB White famously said humour is like a frog — you can dissect it but you’ll probably kill the thing in the process. Acts of creativity often aren’t any different.

True creativity is not just more than the sum of its parts, it is the way those parts are wielded; deftly brought together in a way that even the creator struggles to articulate.

In his unsubtly titled essay Why AI Will Never Rival Human Creativity, William Deresiewicz presents the case that artificial intelligence can never produce something truly novel. Computing models, in their current configuration at least, draw on an existing body of knowledge to produce the most logical outcome to whatever input it is given. By nature, it would be logically impossible for it to produce an act of genius.

The human creative is the antithesis of this. At every point in her process she looks to make an uncommon choice, to bifurcate and make an unpredicted rupture in the decision tree.

Every splash of a Jackson Pollock came from a brush that wasn’t animated by logic or precedent but by inspiration … perhaps even divine madness.

These poets, Plato says, are consumed by a divine madness. The word is not used with the mental health connotations that it is today but rather indicates the state the artist assumes that enables him to produce something beyond mortal capabilities.

A second opinion

There is a vast body of work on cannabis and creativity. Reputable researchers have found evidence to support any viewpoint that it’s possible to hold on the question’s spectrum. Why there is such variability is not hard to speculate on when we’re swimming in so many variables.

Weed potency is an obvious one. In today’s cultivated world of “Cheetah Piss” and “Sour Diesel”, different strains, by design, have very different effects. Some claim to stimulate, others to stupefy.

Online database Leafly has more than 5 000 Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica variations catalogued, all scored and ascribed a set of properties. Even if we account for the likelihood that many of those are stoner platitudes or marketing jazz, there’s no denying that the plant is not a homogeneous entity in any one region, let alone the planet.

That’s before we even consider the controls of consumption — smoking, ingesting or vaping.

Time, setting and mood are also all impossible to keep uniform across hundreds of tests. Hypothetically, if cannabis did boost creativity, what timeframe would display the evidence? Do ideas appear immediately or do they need time to gestate?

In delving into this debate, popular neuroscientist Andrew Huberman found a great deal of logic in a 2017 paper by Emily M LaFrance and Carrie Cuttler titled Inspired by Mary Jane? Mechanisms Underlying Enhanced Creativity in Cannabis Users.

Their research differed in that instead of comparing an intoxicated group to a sober one, marijuana users were measured for creativity next to non-marijuana users — but while both groups were sober.

The smokers trumped their counterparts for creativity.

In their discussion points, LaFrance and Cuttler highlight openness to experience as the key personality trait driving the difference which, even to the layman, makes sense.

People with a willingness to experiment with substances are similarly likely to have an openness towards toying with new ideas, a key asset of divergent thinking.

Huberman added that reduced anxiety is another related facet. A propensity to being relaxed naturally marks us more conducive to open thinking and receptive to new ideas.

Rather than be a cause for cheer for cannabis creativity activists, the study harms their case because it eliminates the need to imbibe to harness their best ability. When the researchers controlled for the personality traits of the two groups they found no difference in score results between them.

The natural defence is to resort to the chicken or the egg question. Are more open people more likely to smoke weed or are they more open because they smoke weed?

A new high

There is an argument to be made that Homo sapiens has an inherent drive to alter his state of consciousness.

In Botany of Desire, Michael Pollan contends that Inuit society is the only one on record that is an exception to the rule, for the obvious reason that psychoactive plants do not fare well in the snow (and even that changed after the white man introduced alcohol to their culture).

Whether through caffeine, grain fermentation, combustion or even meditation, most of us actively desire at some point to transcend our ordinary states and experiences of the world.

Even young children, Andrew Weil points out, chase this urge by spinning around until dizzy and experimenting with hyperventilation. Any parent will also testify to the deranged mania of a sugar high.

It reasons that altered states of perception naturally change our interpretation of the world and our reaction to it. Pollan writes: “One of the things certain drugs do to our perceptions is to distance or estrange objects around us, aestheticising the most commonplace things until they appear as ideal versions of themselves.”

An “ideal version” is a nod to Plato’s theory of the form — a tenet of Western philosophy — that maintains most physical objects are a poor imitation of the idea of that object.

This probably strikes a chord with anybody who enjoys a cannabis high. The world becomes a little brighter, revealing beauty in the mundane. Ergo, it’s easy to understand why recipients in the Washington study scored creative efforts higher when under the influence.

In 1969, scientist Carl Sagan wrote an illuminating essay on his discovery of pot as a young man. He published under the pseudonym Mr X, wary of how taboos might affect him professionally, with his authorship revealed only after his death in 1996. He articulates, as well as anyone could, the mysterious creative impulses some people experience on cannabis.

“For the first time I have been able to hear the separate parts of a three-part harmony and the richness of the counterpoint. I have since discovered that professional musicians can quite easily keep many separate parts going simultaneously in their heads, but this was the first time for me.

“Again, the learning experience when high has at least to some extent carried over when I’m down. The enjoyment of food is amplified; tastes and aromas emerge that for some reason we ordinarily seem to be too busy to notice. I am able to give my full attention to the sensation. A potato will have a texture, a body, and taste like that of other potatoes, but much more so.”

Subjective perceptions of a potato’s contours, regrettably, do not disprove the study that began our journey. Which is not what we should be trying to do anyway.

The truth that even the cannabis advocate must face up to is that we need studies like this one. The seven-pronged marijuana leaf has been the ultimate symbol of counterculture for so long — that invariably changes when you welcome it into statutory everyday life.

There is value in figuring out its role in all levels of society from business to sport, as unpalatable as that might sound to the subversive artist.

And superseding any research or argument is the user’s discretion. Jobs, Lady Gaga or any other pro-pot artist will acknowledge the plant’s limitation as a tool. As much as it might offer occasional inspiration, it will never birth, cultivate or sustain genius.

Believing as much is a fool’s hope — or just a poor excuse to get high. And so we must declare that to the smoker and the scientist alike, the secrets to genius remain unmapped. Despite reports to the contrary.