Despite earning less than R5 000 a month, more than half of South Africa’s Generation Z are somehow saving up to R1 800 a month.

When it comes to taxes, South Africa is an intriguing case. We tax exceptionally well. In fact, our 28% tax-to-GDP ratio is in line with countries like the US (26.5%), Switzerland (28.5%) and Australia (29.5%). The average for the African continent is just over 15%.

The intriguing part is that, unlike similar-taxing countries, South Africans experience none of the social or economic progress that such high taxes would predict. There is no collective-gains argument that we can make to justify the taxes we pay, contrary to what one would expect in a constitutional democracy.

Recently, when the first mini budget of the government of national unity was read, much was made of the fact that it was a pro-growth budget. It is common to analyse budgets as either “pro-poor”, prioritising consumption types of expenditure that directly support the vulnerable members of society, or as “pro-growth” and leaning towards capital expenditure, especially investment in infrastructure.

Not that pro-poor and pro-growth budgets are mutually exclusive; economic growth produces the resources needed to assist the poor and a healthy, educated population is more economically productive than a defeated one.

But, at least in the immediate term, there appears to be a trade-off between meeting the (rather enormous) pro-poor and pro-growth pressures on the budget, which is a real quandary seeing that we can hardly afford to sacrifice one for the other. In either case, however, budgets are sold as a positive instrument that works towards the collective good of society through public expenditure on social and economic programmes.

At least for the past 15 years, however, this has not been the case in South Africa. To start with, our taxes are not spent towards economic growth. If they were, our unemployment would not be the highest globally and half of our population would not need to subsist on small, tax-funded grants.

The fact that they do, is also not testimony of pro-poor inclinations in our fiscal policy but quite the opposite. It is an attempt to compensate the rising numbers of poor and vulnerable citizens for the anti-poor governance that they endure. It is an admission that the poor have been failed.

Our taxes have ceased to be a positive tool in society, one that would normally be justified on a collective-gains basis. Our taxes have ceased to be either pro-poor or pro-growth. The political elite have managed to divert our taxes towards their interests.

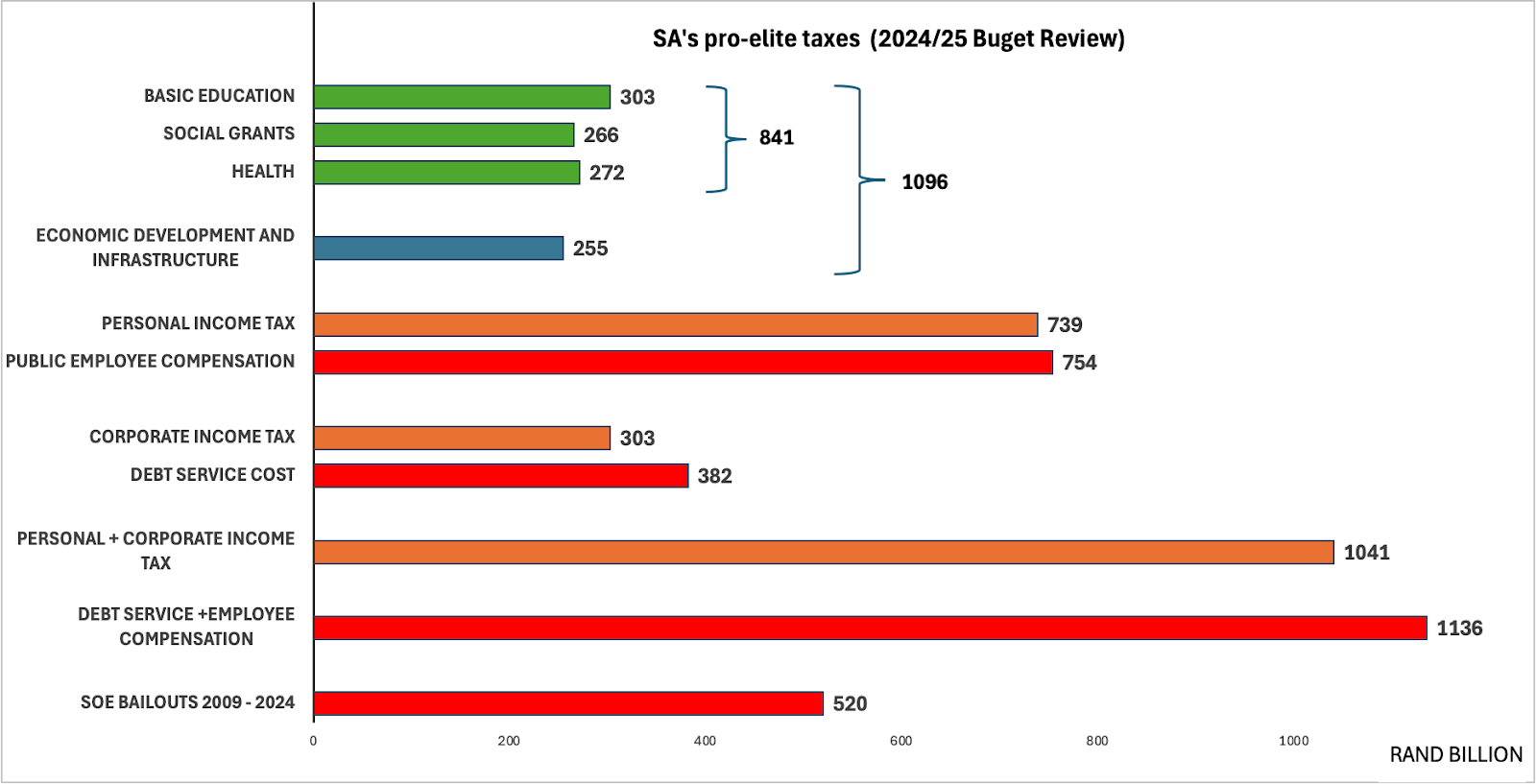

Using data from the Budget Review 2024-25, the bar chart below demonstrates how society’s interests have become deprioritised in the allocation of tax revenue.

The green bars show the most important components of pro-poor government expenditure, on health, basic education and social grants. The grants, at R266 billion, translate into an average monthly grant of about R740 for each of the 30 million or so citizens that depend on them, well below the national food poverty line of R796.

This is not to argue that we can afford to budget more for social grants or that the poor should not receive grants. The issue is with the 30 million who are forced to divvy up the grant allocation. In a functional democracy, a tiny fraction of the population should have to rely on state aid while the majority are productive taxpayers.

So, the 30 million should be, perhaps, a well looked-after 10 million? Or 5 million? Basic education is the largest of the three pro-poor items, accounting for 13% of government’s expenditure. This exceeds what the top-ranking countries on global education indices pay for their public education. We however rank at the bottom of these indices.

Added together, the three green bars reflecting the pro-poor priorities account for R841 billion or 36% of government expenditure.

The blue bar represents the pro-growth expenditure on infrastructure, industrial development, innovation and so on. At R255 billion, this accounts for less than 11% of government expenditure. In fact, adding the crucial pro-poor and pro-growth expenditures together, at R1 096 billion, still only accounts for 46% of government expenditure.

Where then do our hard-earned taxes go?

Well, largely towards the compensation of 1.3 million public employees. At a total wage bill of R754 billion, they receive an average salary of more than R580 000 and account for a third of the government’s expenditure.

For a sobering perspective, one should consider that even the total of R739 billion personal income tax paid by the less-than-10% of the population who are liable for income tax is not enough to cover the salaries of government employees. This says a lot, given that the highly concentrated personal income tax is the largest single contributor of our tax revenue, nearing a share of 40%. Much more than the broad-based value-added tax, for instance.

The qualitative dimensions of this scenario matter too, for instance, how cadre deployment was used to replace career public officials and the conspicuous declines in service delivery and accountability. This reflects the pro-elite workings of our taxes.

The bar chart further shows how rapidly our debt-service cost has risen. Largely driven by the rise in employee compensation, the interest on our public debt costs more than any of the pro-poor or pro-growth budget items. In fact, our entire corporate income tax take is insufficient to cover the interest on our public debt.

Employee compensation and debt service costs together, at R1 136 billion, account for nearly 50% of our government expenditure — quite a bit more than the sum of the pro-growth and pro-poor expenditures.

All our personal and corporate income taxes, at R1041.4 billion, cannot pay for these two elite-serving items that dwarf the pro-poor and pro-growth items in the budget. One might say that, instead of our government working for us, every corporate and individual income taxpayer works to pay government salaries.

The tax-funded bailouts for state-owned enterprises are a further indication of the scale on which taxes have been diverted towards the elite through the manipulation of the tender system and preferential procurement rules. Most of the R520 billion used to bail out state-owned enterprises since 2015 was funnelled into Eskom and Transnet, while their operational failures paralysed the supply side of our economy, the results of which we see in our stagnant growth and unemployment.

One can only imagine what the counterfactual would have been had this enormous amount gone towards infrastructure development and had the pro-growth agenda been real rather than a well-spun myth.

Dr Sansia Blackmore is a tax policy expert at the African Tax Institute, University of Pretoria.