It is crucial not to overlook the Apies River as a potential contributor to the situation in Hammanskraal. (Facebook)

Following the cholera outbreak in Hammanskraal, Tshwane metropolitan municipality, the urgent need to identify its source has become paramount.

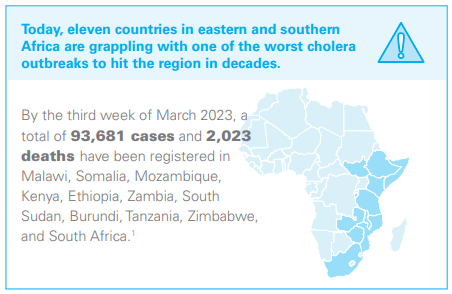

While the origins remain unknown, it is crucial not to overlook the Apies River as a potential contributor. With a staggering cumulative count of 93,681 reported cholera cases in eastern and southern Africa as of March 2023, it is essential to contextualise this outbreak as part of a larger, expanding trend.

South Africa is not immune to the grip of this crisis, and it is imperative that we take immediate action to address it. To effectively respond to this emergency, United Nations Chidren’s Fund (Unicef) has proactively allocated its core resources, dedicating significant funding to combat the outbreak. However, a crucial funding gap of $300,000 has been identified in South Africa.

In light of this, it is my strong recommendation that we declare the cholera outbreak a national pandemic without delay. Such a declaration would unlock access to additional funding from organisations like Unicef. These funds can then be allocated to the development of intensive river rehabilitation and water resources management projects, aimed at conserving and enhancing our rivers from catchment to coast.

Prioritising river conservation and monitoring is the only viable solution to combat not only the current Cholera outbreak but also other waterborne pathogens such as Escherichia coli (E.coli).

By implementing comprehensive and sustainable river conservation strategies, we can proactively prevent outbreaks, safeguard public health, and expedite the achievement of sustainable development goals.

Through this proactive approach, we can mitigate the impact of the cholera outbreak, protect our communities, and foster a healthier future for all.

Figure 1: Infographic of cases and mortalities of cholera in eastern and southern Africa (Unicef).

Cholera is a highly infectious and potentially life-threatening disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It is primarily transmitted through contaminated water and food, particularly in areas with inadequate sanitation and poor hygiene practices.

When untreated, cholera can lead to severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalances and even death.

In the wake of the cholera outbreak, it is disheartening to realise that the causes of this devastating crisis might have been lurking for years. Newspaper reports have highlighted the escalating casualties, with at least 17 lives lost, and more than 40 hospitalised, as authorities struggle to identify the source of the outbreak and respond timely and with tact.

During times of crisis, we witness a surge in reporting from journalists and civic society, which, while commendable for providing near real-time information, often leaves little room for thorough analysis and understanding.

So, let’s do it together.

Starting from the beginning, it was reported that the deaths resulted from the consumption of contaminated drinking water. However, as events unfolded, water samples from certain tested outlets showed negative results. The quest for a positive cholera test symbol from tap water in the affected areas continues, though it is premature to rule out the possibility of tap water contamination that remains undetected.

To gain a comprehensive perspective, let us further examine the available facts individually. Firstly, cholera has been confirmed as the cause of death, with reported deaths and infections concentrated in specific localities. Secondly, we know that cholera is a highly infectious waterborne disease, meaning that anything encountering contaminated water is at risk of becoming infected and becoming a carrier.

“Thus, we should expect officials to test all water bodies near the reported infections, rather than solely focusing on tap water. This lack of systematic implementation and negligence is a part of the problem,” the report said.

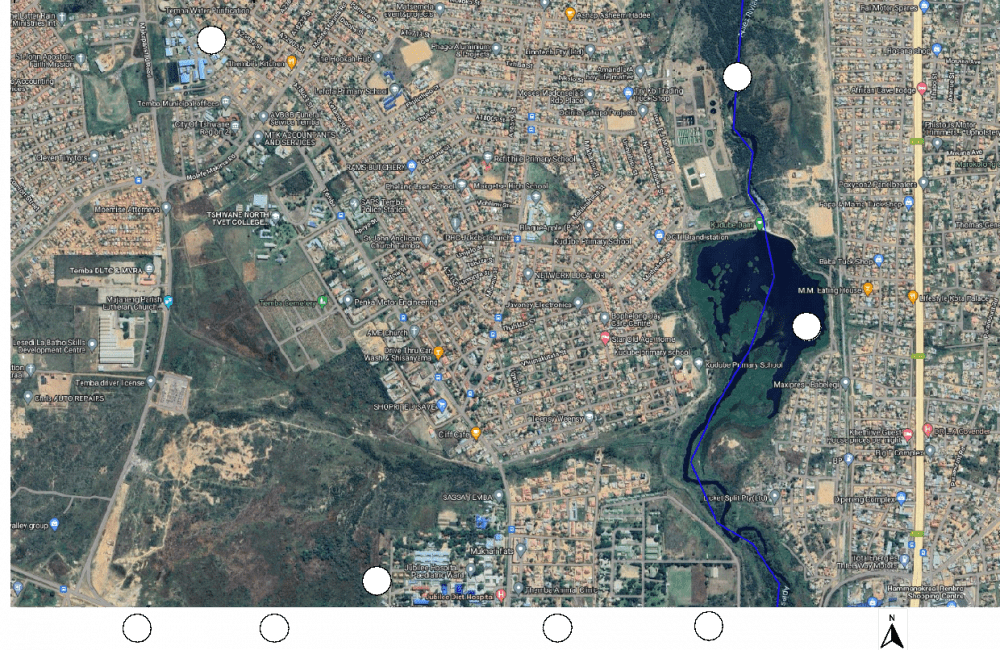

Following this line of thought, our attention turns to the river network associated with this cholera outbreak. Analysing the river network requires the use of advanced GIS technologies, but it helps us understand the connection between the two affected locations — Moretele and Hammanskraal.

By overlaying these locations onto the river network, a clearer picture emerges, revealing that the Apies River serves as a vital link between the two areas. Could the Apies River be the missing link in unravelling the Tshwane-cholera conundrum?

Figure 2: Google aerial image of the locality of the cholera outbreak, Hammanskraal. The blue line indicates the path of the Apies River, passing through the Kudube dam. The designated local hospital providing medical care to the cholera patients is the Jubilee Hospital and one of the nearest water purification sites that was a suspected source, Temba Water purification site but has since had its water tested negative, together with others. It is not known whether water from the nearby Apies River has been tested.

Regrettably, the Apies River stands as one of the most contaminated rivers within the expansive Limpopo River basin. It is a tragic reality that many Gauteng residents are unaware that they reside within the catchment area of one of South Africa’s largest and most crucial strategic water resources.

The significance of the Limpopo River Basin extends beyond its vastness and the support it provides to a substantial human population and biodiversity.

The economies of three African countries rely on the Limpopo River Basin, magnifying our concerns beyond the contamination in Tshwane to potential impacts on neighbouring Province Limpopo, and neighbouring nations.

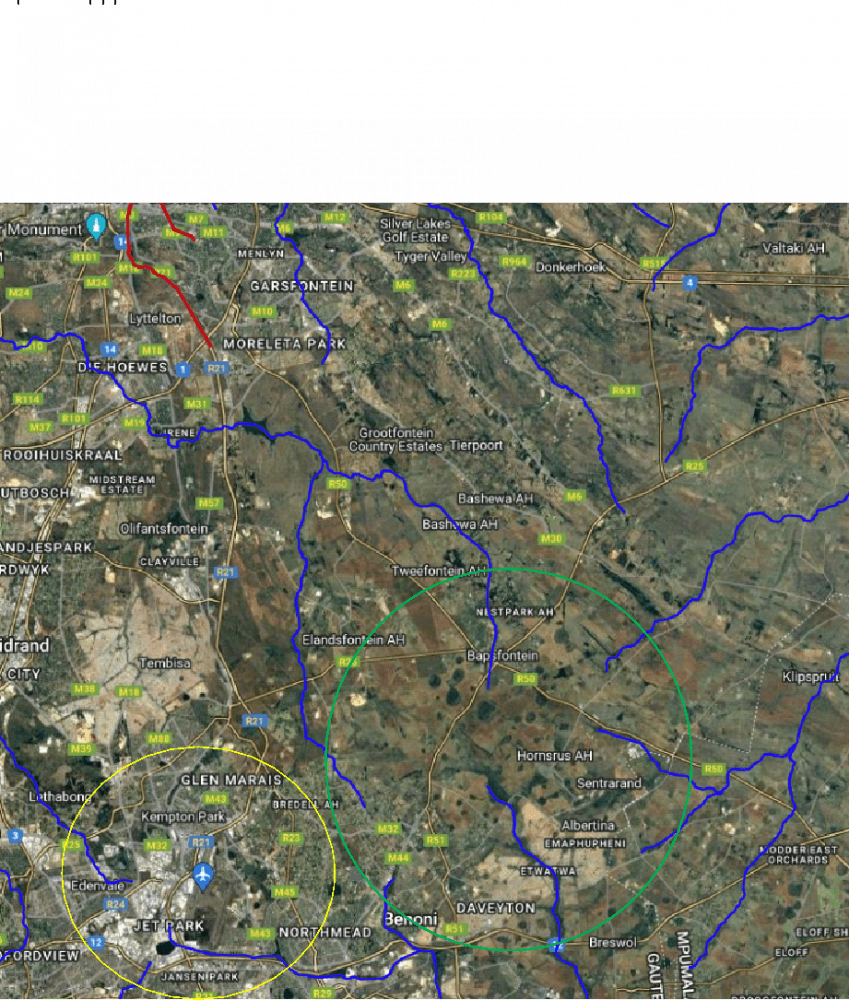

The Apies River draws its water from the Bapsfontein Lake District, located just northeast of Johannesburg. It acts as a major water source for numerous tributaries of the Limpopo River valley, rendering it a critical water source area.

However, the Apies River connects to the Gauteng lake district via the Rietvlei dam, and it is alarming how rapidly the river becomes polluted as it meanders through the capital. An essential contributing factor to the contamination of the Apies River, as well as other water sources within Tshwane, is the prevalence of informal settlements along its banks.

Over the past five years, these settlements have mushroomed, lacking proper sanitation facilities. With no ablution systems and open fields being used as living spaces, it is no surprise that human waste finds its way into the river through rainwater erosion.

The situation is further aggravated by the presence of illegal immigrants who, without proper accommodations, resort to establishing informal settlements in open areas.

Figure 3: The Bapsfontein Lake District (BLD), highlighted by the green circle, is home to valuable depression wetlands that serve as critical water resources. The separate drainage system in the southwest, indicated by the yellow circle, supplies water to Jukskei River. These wetlands are under severe threat of extinction and have limited boundaries. The BLD serves as the primary source of rivers that provide water to the majority, if not all, of Tshwane. Despite the strategic importance of this water-rich area, there is no conservation programme being championed by local municipalities or the Gauteng government.

To address this alarming situation, the city must recognise the importance of preserving green spaces and natural environments within its boundaries. It is crucial to ensure that areas along waterways and rivers are not inhabited by informal dwellers and are regularly cleaned to prevent litter, invasive and alien vegetation from contaminating the waterways.

As the deadly cholera outbreak rages on, shedding light on the polluted Apies River and its potential role in this crisis becomes increasingly urgent.

Swift action is needed to investigate and mitigate the contamination of Apies River, not only to safeguard the health of Tshwane residents but also to protect the Limpopo River basin and the countries that rely on it. A proposal is thus made to the Apies River Conservation Programme, a proposal for a sustainable response to cholera and other waterborne disease outbreaks in Tshwane.

The time for comprehensive measures to tackle this pressing issue is now.

Figure 4: The Limpopo River Basin (LRB) is an internationally important river basin. On the left side of the figure, a detailed network of the South Africa River network is depicted, derived from the rivers in all drainage regions – 1:500 000 dataset. On the right side, the tributaries are annotated according to information provided by the South Africa Research and Documentation Centre. Apies River in red.

The question on whether or not the rivers are the source of the cholera outbreak should not derail us or confuse us between that question and the question on whether or not the rivers in their current state have a potential to give rise to a cholera outbreak.

It is crucial that we approach the situation with clarity and precision. It is important to distinguish between two distinct questions that may arise: whether or not the rivers are the direct source of the outbreak, and whether or not the rivers, in their current state, have the potential to facilitate a cholera outbreak.

While the former question may garner significant attention and fuel debates, it should not divert our focus from the latter, which is of equal if not greater importance. By separating these inquiries, we can navigate the issue with a more comprehensive understanding.

Acknowledging that the rivers may not be the direct cause of the outbreak does not dismiss the urgent need to assess their condition and potential as a conducive environment for cholera transmission. Therefore, we must remain vigilant in our efforts to address both questions concurrently, ensuring the well-being and safety of our communities.

In light of the aforementioned context, it is essential to present concrete evidence that addresses the second question regarding the potential of rivers, specifically focusing on sections of the Apies River, to harbour human faecal matter and other waste materials.

By examining specific examples, we can shed light on the likelihood of contamination and prolonged presence of these substances in the river. One such instance is the Marikana informal workers camp, located along West Avenue, near the Gautrain station in Centurion.

This settlement lacks sanitation facilities, leading to a significant risk of waste finding its way into the Apies River. Additionally, another area of concern is the intersection of Willow Road and Nelson Mandela Drive, extending through the CBD and reaching the national zoological gardens.

At the zoological gardens, measures have been implemented to capture floating litter from the Apies River, such as papers and plastic, indicating the presence of pollutants in the water. Moreover, the extraction of tons of lead from the river each year further highlights the potential for contamination.

These examples serve as compelling evidence supporting the notion that the Apies River, along with possibly other rivers, is at a high risk of being affected by human waste and other detrimental substances for extended periods; thus, are conducive conditions for a cholera outbreak and river cleaning and protection should be done urgently.

Figure 5: A collage showcasing unsanitary conditions the Marikana informal workers camp, situated alongside the Apies River.

The collage portrays the lack of sanitation facilities, with open defecation being a common practice, leading to the direct contamination of the river. In the next image, one can observe the intersection of Willow Road and Nelson Mandela Drive, displaying a bustling urban area where various waste materials and pollutants are disposed of haphazardly. These precursor conditions for cholera development in the Apies River, create a compelling visual narrative.

The images showcase garbage strewn around the river, illustrating the detrimental consequences of such practices. These visuals highlight the potential for various pollutants, including pathogens, chemicals and non-biodegradable materials, to enter the river ecosystem, exacerbating the risk of cholera contamination.

Collectively, these pictographic representations serve as a stark reminder of the multiple factors at play in the Apies River that contribute to its contamination and the subsequent risk of cholera outbreaks.

They highlight the urgent need for improved sanitation infrastructure, proper waste management practices and remediation efforts to mitigate the potential transmission of cholera and safeguard the health and well-being of communities relying on the river as a water source.

To prevent cholera in rivers, it is crucial to implement specific measures aimed at reducing the risk of contamination and transmission. Here are some specific and direct steps that can be taken:

- Ensure that communities living near rivers have access to hygienic toilets and sewage systems. Adequate sanitation infrastructure helps prevent the direct discharge of human faecal matter into the river, reducing the chances of cholera contamination.

- Encourage proper waste management practices, including the use of designated garbage bins and recycling facilities. Discourage littering and educate communities on the potential risks associated with improper waste disposal, which can contaminate the river and contribute to cholera transmission. Assist communities to facilitate their garbage collection activities as organised collection instead of trollies and sacks.

- Implement effective water treatment methods, such as filtration, chlorination, or ultraviolet (UV) disinfection, to ensure that water from the river is safe for consumption. Regular monitoring and testing of water sources for bacteria can help identify potential risks and enable prompt interventions. Remove alien vegetation that cover the water surface and prevent UV from reaching the water of invasive bushes that create shade along the river course.

- Promote regular handwashing with soap and clean water, particularly before handling food or after using the toilet. Proper hand hygiene is critical in preventing the spread of cholera and other waterborne diseases.

- Conduct awareness campaigns to educate communities living near rivers about cholera prevention measures. Focus on topics such as proper hygiene practices, safe water handling, and the importance of vaccination where applicable. Supply containers and coverage rain water harvesting alternatives and provide the necessary support.

- Vaccination development facilities and specialist support at Jubilee Hospital. In areas with high cholera prevalence or during outbreaks, mass vaccination options must be made available. Oral cholera vaccines are available and have shown efficacy in reducing the incidence and severity of the disease. However, the politics of vaccine procurement and development have to be negotiated.

- Engage with local authorities, health organisations and community leaders to implement comprehensive strategies for cholera prevention. This collaboration can involve regular monitoring, early detection of outbreaks, and prompt response to control the spread of the disease. Build discussion forums with municipalities and organisations in Malawi that have extensive experience in dealing with diseases, while also valuing and respecting the insights of local scientists who possess a deep understanding of the unique context of South Africa.

By implementing these specific preventive measures, it is possible to minimise the risk of cholera in rivers and protect the health of communities relying on them for water resources.

Basanda Nondlazi is a postdoctoral researcher with a current focus on holistic climate change.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.