A student responds to a teacher’s question in an overcrowded classroom at a public primary school in Kaya, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. In January 2020, the school had 748 students, including 113 displaced students. “Each day, the displaced students come... we don’t refuse enrolment, but if there isn’t any space they can’t start,” the principal said. (© 2020 Lauren Seibert/Human Rights Watch)

The children who were still attending class at the Toulfé village school on the afternoon of November 12, 2018 were struggling to focus. It was late in the day. But that was not the reason for their lack of concentration. They were worried, Grégoire (not his real name), a member of the school’s staff, knew. “We were … living in [a state of] psychosis,” he says.

A picture of members of Burkinabe Islamist group Ansaroul Islam during a gathering in 2017. © 2017 Héni Nsaibia/ MENASTREAM

A picture of members of Burkinabe Islamist group Ansaroul Islam during a gathering in 2017. © 2017 Héni Nsaibia/ MENASTREAM

Situated in Burkina Faso’s Loroum province, near the border with Mali, the school — the only middle or junior high school within a 4km radius — was located in a region that had seen an increasing number of attacks by armed Islamist groups that year. Schools had become a prime target and the learners knew this. It was with growing apprehension that they pursued their education.

In many corners of Burkina Faso’s border area with Mali and Niger, schools were burning, teachers were kidnapped or killed, and parents terrorised into keeping their children out of school. For the village of Toulfé, in Nord region, the relentless attacks on education would prove disastrous. As documented in a new Human Rights Watch report, Their War Against Education: Armed Group Attacks on Teachers, Students and Schools in Burkina Faso, teachers and young people are bearing the brunt of the conflict.

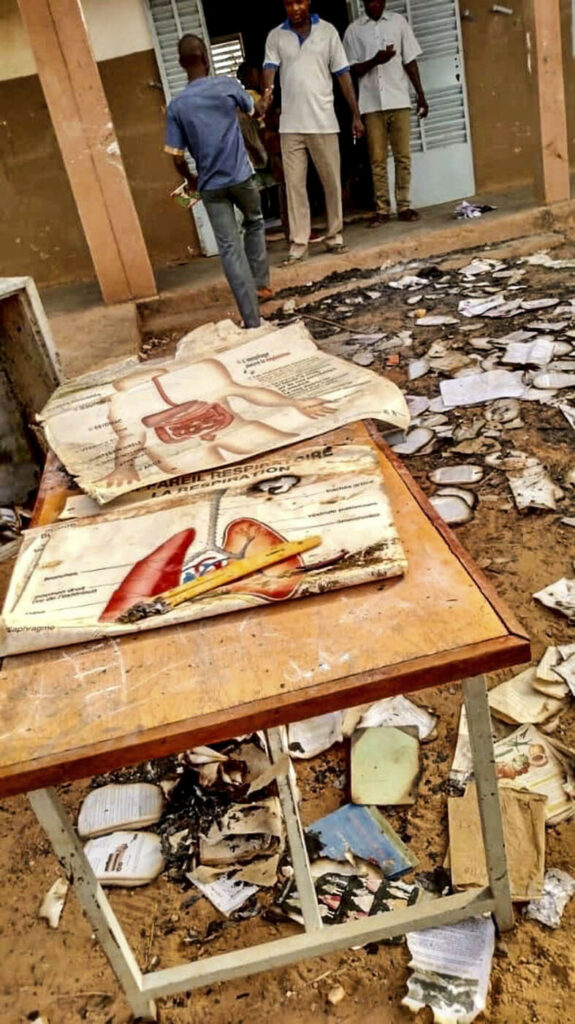

Teachers and villagers inspect the damage at Sillaléba village primary school in Nasséré commune, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso, after an attack in April 2019. Attackers started fires in three classrooms, burned school materials, damaged five motorcycles, and stole three motorcycles and a computer. (© 2019 Harouna Sawadogo)

Teachers and villagers inspect the damage at Sillaléba village primary school in Nasséré commune, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso, after an attack in April 2019. Attackers started fires in three classrooms, burned school materials, damaged five motorcycles, and stole three motorcycles and a computer. (© 2019 Harouna Sawadogo)

By that November day, the armed Islamists were fast achieving their goal to shut down French, Western-style education. Hundreds of schools had already closed and teachers gone into hiding. “Fear”, a United Nations Children’s Fund report said at the time, was “widespread”.

Time and again, the children at Toulfé Middle School looked out the windows, anxiously scanning the school yard. Three weeks earlier, a health centre had been attacked and a school building set on fire in a nearby village. A few months prior to this, during an attack on a primary school in Soum, a neighbouring province, a schoolgirl had been shot and killed and a teacher abducted. One of these days, they feared, the “jihadists” would come to Toulfé, too.

Grégoire heard the schoolchildren’s screams before he saw the attackers: four men in military fatigues who had arrived on motorcycles, AK-47 assault rifles over their shoulders and ammunition belts draped around their waist. With the cloth from their turbans wrapped around their heads and faces, only their eyes were visible. It was a terrifying sight.

Stunned, Grégoire watched as children began vaulting out the windows and running for safety. Those who didn’t get away in time were ordered to get down on the ground. Then the attackers came for him and his colleagues. “One pointed a gun at me,” Grégoire recounts. “He said … he was there for jihad [and] they’d already said to stop teaching French, so why were we still teaching French…. Then one asked the other, ‘Should we shoot them?’”

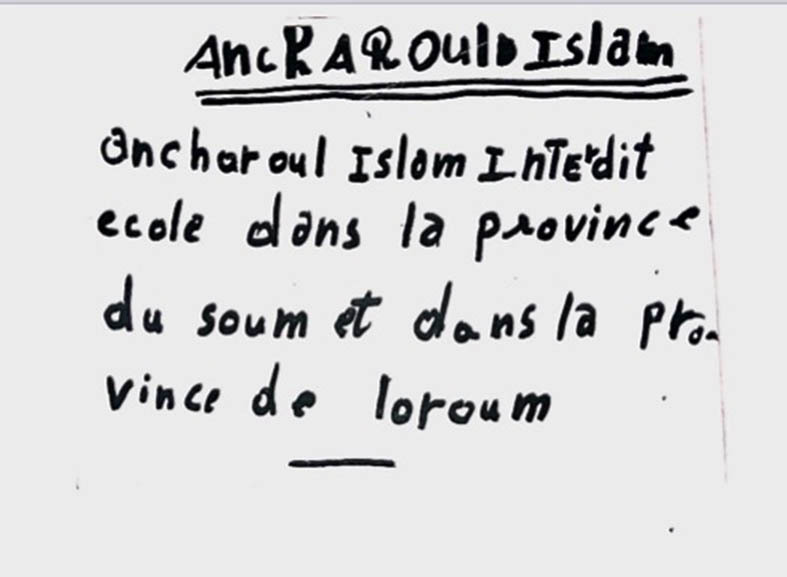

Grégoire and his colleagues were flogged instead, one by one, while lying face down in the dust, with guns trained on them and their learners looking on. When the attackers retreated, having set fire to one of the school’s offices, they left behind traumatised people and a message “for the Burkinabé authorities” demanding the closure of all schools in the provinces of Soum and Loroum. “After this warning, if we find a teacher teaching, we will kill him,” the note scribbled on a piece of notebook paper read. “Democracy [is] barred.” It was signed “Ansaroul Islam”, a militant group.

The note that the attackers at Toulfé handed the victims to “transmit to the Burkinabè authorities… [and] to the President” – it says:“Ansaroul Islam forbids school in the province of Soum and the province of Loroum. After this warning, if we find a teacher teaching we will kill him. Democracy barred.”

The note that the attackers at Toulfé handed the victims to “transmit to the Burkinabè authorities… [and] to the President” – it says:“Ansaroul Islam forbids school in the province of Soum and the province of Loroum. After this warning, if we find a teacher teaching we will kill him. Democracy barred.”

Since the emergence of this group in 2016, Burkina Faso has been grappling with a surge in armed attacks, spreading from central Mali to Burkina Faso’s northern Sahel region. Between 2017 and 2020, there have been at least 126 attacks on education professionals, schoolchildren, and schools by Ansaroul Islam and other groups allied with Al Qaeda or the Islamic State that Human Rights Watch was able to document. Dozens more attacks were reported by the media and local sources.

Abusive counterterrorism operations by state security forces have aggravated the situation. As a result, people have been fleeing the conflict zones in droves. Today, the once-relatively stable country is shattered by the world’s fastest-growing displacement crisis and Toulfé is a ghost town. “Not even one person stayed in the village,” says Grégoire.

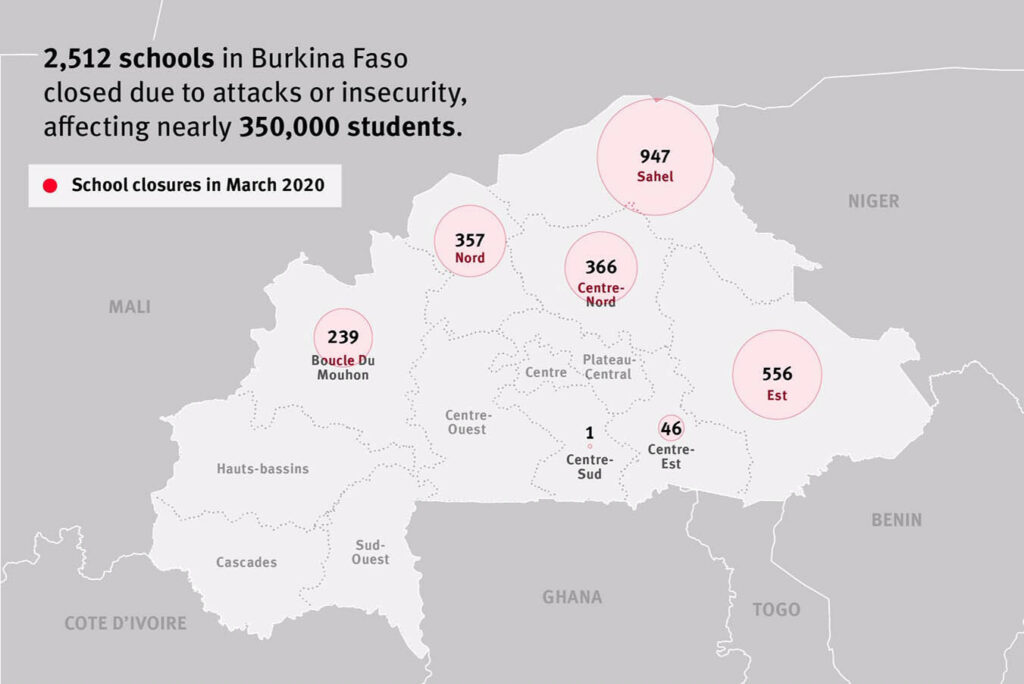

Hundreds of schools have been burned, looted and destroyed, exposing children to an uncertain future. By March this year — before the coronavirus pandemic led to the general closure of schools — nearly 350 000 children were unable to continue their education. The attacks have reversed decades of progress in increasing school attendance. Thousands of teachers have fled their posts. So, too, has Grégoire.

A gendarme holds a piece of an improvised explosive device (IED), which was set off during an attack on April 15, 2019 on Nebkieta Private High School in Pissila, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. The explosion damaged equipment, shattered windows, and caused the ceiling to fall down in the computer room. ( © 2019 Joseph Ouedraogo)

A gendarme holds a piece of an improvised explosive device (IED), which was set off during an attack on April 15, 2019 on Nebkieta Private High School in Pissila, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. The explosion damaged equipment, shattered windows, and caused the ceiling to fall down in the computer room. ( © 2019 Joseph Ouedraogo)Like almost everybody interviewed by Human Rights Watch researcher Lauren Seibert for her report, Grégoire wants neither his real name nor his present location known. Even a year and a half after the Toulfé attack, he is scared his attackers will track him down. He is not aware of any official investigation of the incident, nor was he ever offered counselling. “We had the impression we were abandoned to ourselves,” he says, a notion that is painful for him.

Psychological support for teachers and children who experienced attacks has remained inadequate. Like Grégoire, many still suffer from anxiety and nightmares, have difficulties sleeping or are afraid to be out after dark. “For months after the attack I used to wake up and cry out loudly,” Grégoire recounts. To this day, the sound of motorcycles startles him. “You never know who’s coming,” he says.

These days, however, it is the thought of the children and their “lost chance to succeed” that keeps him up at night.

A map illustrating the number of schools that had been shut down by 2020

A map illustrating the number of schools that had been shut down by 2020

While the government, with assistance from aid agencies, has taken measures to strengthen schools’ capacities to plan for and respond to potential attacks, these initiatives have only reached a small portion of schools in the affected regions, leaving many vulnerable.

An IED attack on April 15, 2019 damaged computers, shattered windows, and caused the ceiling to fall down in the computer room at Nebkieta Private High School in Pissila, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. The school remained closed for the 2019-2020 school year. (© 2019 Joseph Ouedraogo)

An IED attack on April 15, 2019 damaged computers, shattered windows, and caused the ceiling to fall down in the computer room at Nebkieta Private High School in Pissila, Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. The school remained closed for the 2019-2020 school year. (© 2019 Joseph Ouedraogo)Efforts to reintegrate displaced children into schools in safer towns has led to overcrowded classrooms. With some class sizes stretched to as many as 150 pupils with only two teachers, schools are saturated and unable to enroll the ever-growing number of children fleeing from areas that have come under attack. “What will become of these children?” Grégoire asks.

He knows of many children from Toulfé who did not finish the 2018-2019 school year because parents were unable to re-enroll them elsewhere. Like so many others whose schools were shut down or who were displaced, the children are now working as street vendors, domestic workers, brickmakers and in Burkina Faso’s many artisanal gold mines. Girls are particularly at risk of early marriage, domestic violence and sexual abuse.

Students sit crammed up to five at desks meant for two, in overcrowded classes of up to 125 students, at a primary school in Kaya, a town hosting tens of thousands of displaced people in Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. January 29, 2020. (© 2020 Lauren Seibert/Human Rights Watch)

Students sit crammed up to five at desks meant for two, in overcrowded classes of up to 125 students, at a primary school in Kaya, a town hosting tens of thousands of displaced people in Centre-Nord region, Burkina Faso. January 29, 2020. (© 2020 Lauren Seibert/Human Rights Watch)

With so many children missing out on an education, quite a few might become vulnerable to recruitment drives by armed groups, warns Jacob Yarabatioula, a Burkinabè researcher specialising in terrorism. “That’s what the terrorists want — children to be ignorant, so they can influence them and put whatever they want in their heads,” he says. “We all should fear this.” Grégoire shares these concerns. “The government needs to help these students,” he says. “If you let them grow up like that, just wandering around, it could be a problem later.”

Burned academic materials on a teacher’s desk in Minima village primary school, Centre-Nord region, following an attack by armed Islamists on May 2, 2019. “They broke the [door to the school’s] office and set fire to the notebooks, the students’ homework, records, documents—everything,” said the principal, Noufou Niampa. “There are no longer any records for the Minima school.” June 13, 2019. (© 2019 Noufou Niampa)

Burned academic materials on a teacher’s desk in Minima village primary school, Centre-Nord region, following an attack by armed Islamists on May 2, 2019. “They broke the [door to the school’s] office and set fire to the notebooks, the students’ homework, records, documents—everything,” said the principal, Noufou Niampa. “There are no longer any records for the Minima school.” June 13, 2019. (© 2019 Noufou Niampa)

He would return to his job at Toulfé Middle School tomorrow, he says, provided the staff’s and students’ safety could be guaranteed, something which has proven difficult to ensure as long as armed Islamist groups don’t cease their attacks against schools. “I am ready to go back,” Grégoire says, “for the love of these children.”

This story is based on interviews with and by Human Rights Watch researcher Lauren Seibert.