(Andrew Winning/Reuters)

During the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, some saw an opportunity to push the world’s warring parties toward peace. Combatants now face a “common enemy” that cares little for “nationality or ethnicity, faction or faith” and requires nothing short of an immediate, global ceasefire to confront, said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

In Africa, it was hoped that movement restrictions and fear of infection might halt fighting, creating space for dialogue in even the most intractable conflicts

Yet, as the UN raised hope of ceasefires, other projections indicated that Covid-19 would have a devastating effect on African health systems and economic prospects, destabilising the continent and leading to a spike in violence.

These two forecasts for the future of African conflict were misguided.

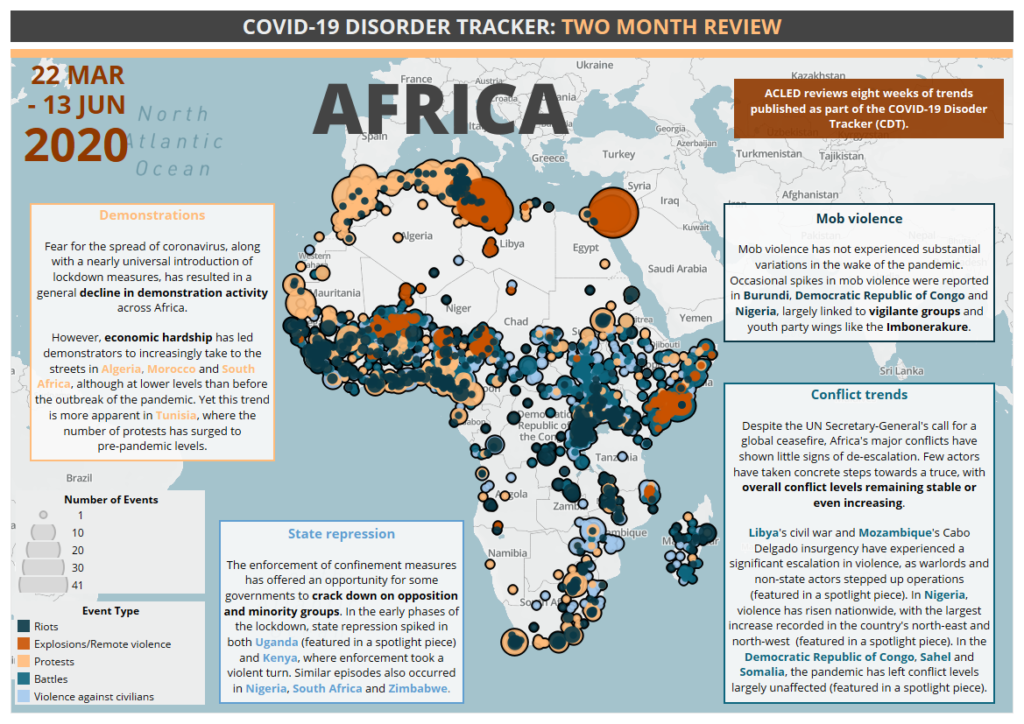

Since the official declaration of the pandemic in March, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) has monitored how African conflict and protests have changed in response to Covid-19. Tracking activity over the past 10 weeks, ACLED found that conflict rates held steady across the continent, but patterns of violence have shifted as armed groups and governments take advantage of the pandemic to make moves on political priorities.

Infographic and data supplied by ACLED

Infographic and data supplied by ACLED

During the pandemic’s early stages, patterns of violence changed in critical ways: governments became more likely to suppress their citizens and crack down on opposition and minority groups, often under the guise of lockdown measures. Violent armed groups expanded their active territories, and inter-group clashes rose by an average rate of 25%. In short, while the governments often targeted their citizens in harsh attempts to control movements, armed groups competed and consolidated their positions.

At the same time, conflict escalated where fighting was already heaviest. Libya’s civil war activity increased. Khalifa Haftar’s renegade Libyan National Army, in early June, suffered several significant defeats at the hands of the UN backed government, supported by Turkey. This did not come about from less violence because of the pandemic, but possibly accelerated as European officials turned to dealing with their domestic crises, and leaving Turkey to scale up military operations. A political solution is unlikely.

In Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, the insurgency activity rate tripled. The Islamic State claims its Central Africa Province branch is behind the attacks. Several paramilitary-style groups are involved in the conflict and insurgents are gaining on several large district towns. Macomia was taken on May 28, making it the fourth district capital to be overtaken in three months.

As noted by the Cabo Ligado project: “… the fundamental dynamics of the conflict remain unchanged — insurgents continue to demonstrate the ability to strike at will within the established conflict zone, government forces remain stretched and unable to provide effective security in the province and civilian confidence in the government’s ability to protect them continues to drop”.

In another example of shifting conflict patterns, Nigeria now has several places in active rebellion. Conflicts in the northwest have grown to attract external interest from Islamic State and Al Qaeda operatives in the Sahel, while internal threats from a resurgent Ansaru — a splinter group of Boko Haram — enters an already unstable situation rife with intercommunal conflict and “banditry”. In this case, as with other areas with high violence rates — in Somalia, the Sahel and the Democratic Republic of Congo — conflict has remained stable or increased in the face of a severe health crisis.

What does this tell us? The shifts in African conflict patterns were not drastically different to what ACLED saw in the rest of the world. In South America, South Asia and the Middle East, conflict continued, if not intensified. In all cases, the conflicts existed before: armed groups and governments have taken the opportunities provided by little domestic and international attention to pursue competitors, opposition and territory.

There are no records of new groups becoming active during the pandemic. But this is cold comfort, and likely to quickly change as people tire of restrictions, limitations and a silent pandemic.

As for citizen actions, compared with 10 weeks ago, protests rates are now resuming their normal (frequent) rate across most countries. Protests and riots decreased by more than 50% in the early weeks of the pandemic. In recent weeks, and in reaction to crackdowns and poor planning of measures to restrict the spread of Covid-19, demonstrations have quickly returned. But the tone of protests has changed: economic hardship demonstrations have increased, particularly in South Africa, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco.

Dr Clionadh Raleigh is the director of the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project and a professor of political geography and conflict at the University of Sussex