A top shot of a powder drug like cocaine in the shape of Guinea (Africa) with a rolled money bill.(series).Inspired by the world we do live in. Photo: Getty Images

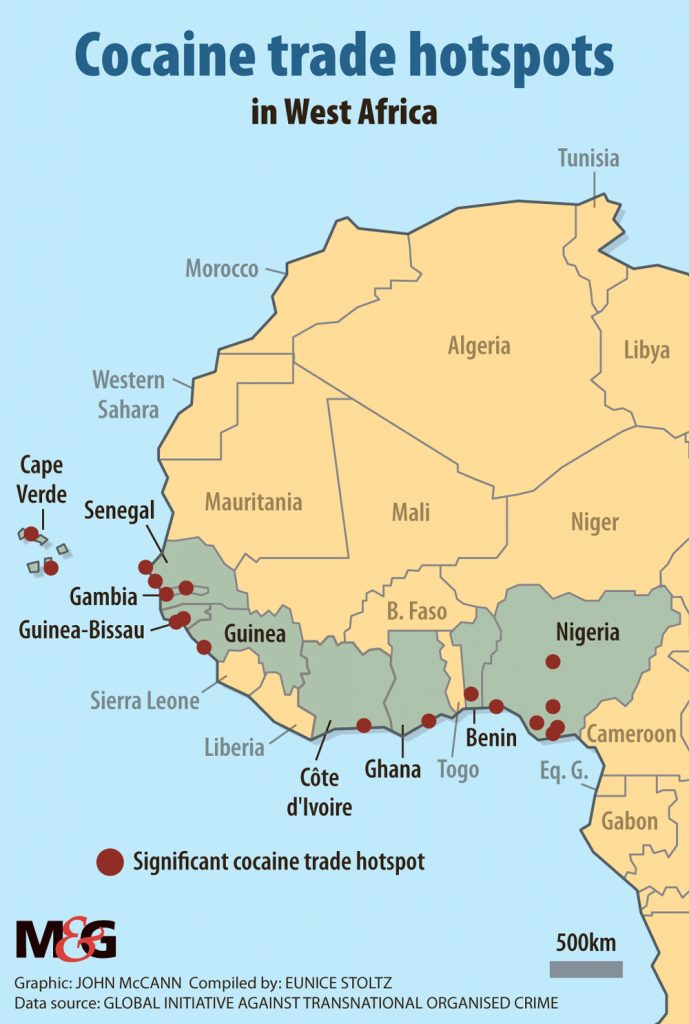

Cocaine traders in West Africa have switched to coastal routes to avoid a rise in conflict between militia groups inland.

According to the latest report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, West Africa is experiencing “unprecedented levels” of armed violence — with the period since 2015 being the most violent on record”.

The Global Initiative, through the Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, identified 280 illicit hubs in 18 countries in West Africa, including Cameroon and the Central African Republic.

One such hub is the cocaine trade, which makes up 23% of all illicit hubs in the region. It is the third most prevalent market in 14 of the 18 countries, after arms trafficking and counterfeit goods.

The report, which comes with an interactive map, illustrates links between illicit economies and a region’s instability. It says the driving force behind the proliferation of violent extremist groups in West Africa is a combination of corruption, poor governance, impunity among state security forces and the socioeconomic marginalisation of people.

There are several hundred illicit hubs in West Africa but the proportion of those that play a key role in fuelling conflict and instability is smaller, with one in four identified as significant drivers of regional instability.

“Transit points or crime zones identified in West Africa were assessed to play a relatively limited role in directly contributing to conflict and instability across the region,” the report says.

“While certain armed groups do earn some revenue from the cocaine trade, it is by no means among the most prominent illicit economies feeding into regional conflict dynamics,” the report says.

In Guinea-Bissau, the cocaine trade is prevalent in seven of the 13 illicit hubs, and competition in the trade is a key driver of political volatility, notes the report.

Graphic- Cocaine Trade; John McCann.

Graphic- Cocaine Trade; John McCann.

In areas where conflict and instability are more prevalent, illicit economies such as the drug trade make use of alternative routes in less volatile parts of the region.

“The potential loss of a consignment to bandits or armed groups — types of groups commonly found in failed states — presents an unacceptable risk to profits,” the report says. “Therefore, while conflict areas often provide an opportunity for illicit market expansion, high levels of instability are likely to result in illicit trafficking routes being displaced elsewhere.”

The surge in armed violence and instability in the Sahel, Libya and Niger has in recent years led to increased costs of trafficking, especially of high-valued commodities such as cocaine and weapons.

“This high level of instability across trans-Sahelian land routes displaced more trafficking to maritime routes,” the report says.

The nearly 17 000km coastline that stretches along 13 countries in West Africa plays a crucial role in transnational and transcontinental illicit flows.

“Bulk supplies of cocaine started to be frequently transferred from Guinea-Bissau through Senegal and on to Mauritania, from where fishing boats are then used to take the commodity to Europe. Alternatively, cocaine is driven over the Senegalese border, on to Mali, and then to Mauritania,” the report says.

Countries in which consumer markets are concentrated — for example Western Europe in the case of cocaine trade — must accept their share of responsibility and continue efforts to address demand for illicit commodities, the report noted.