A fearful reluctance among teachers to talk about sex exacerbates their pupils' risk of contracting HIV and Aids, falling pregnant and being discriminated against on the basis of their sexual identities, academic research into sexual education at schools suggests.

"Teachers couldn't even say the word 'sex' when I spoke to them during my research. They'd say: 's-s-s-sex' or 'that thing' or 'you know what I mean'," said Jean Baxen, a professor of education at Rhodes University.

She was speaking at a two-day colloquium on sexuality, society and pedagogy at the University of the Free State this week. Academics from across the country presented papers on topics that included "sugar daddy" relationships and the teaching of sexuality in South African higher education.

"We need to change the way teachers are taught how to teach sexual education," Baxen told the Mail & Guardian during the colloquium. "We should start with getting teachers to confront their own ideas about sex." The research paper she and her colleague from Rhodes, Lesley Wood, presented at the colloquium, titled Mediating Sexuality and HIV and Aids in Schools: Implications for Teacher Education Preparation Programmes, was based on interviews she conducted with 80 life-skills teachers in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape.

Her project was to provide answers to two questions: Are teachers comfortable and skilled enough to mediate messages about our private lives? And are classrooms the best places to discuss sexuality and HIV and Aids?

Conflict between personal beliefs and professional obligations

The "complex interplay between teachers' individual, social and professional identities and the content taught in sexuality and HIV and Aids lessons do not always enable them to teach in a way that encourages behavioural change", she found.

"For example, teachers found it hard to teach pupils about condoms when they can't even negotiate condom use in their own relationships."

Last month Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi said that 94 000 schoolgirls fell pregnant across the country in 2011. HIV and Aids among pupils also remains an urgent concern: the National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Prevalence Survey in 2009 reported that 13.7% of teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19 were HIV positive.

HIV and Aids in the context of "sugar daddy" relationships was the subject of Cheryl Kader's paper. A Durban teacher studying towards a PhD at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Kader asked how young women handle these transactional relationships when they know they are at risk of contracting HIV because their sugar daddies had sexual relationships with other women.

One of the five women between 18 and 25 she interviewed for the paper said she didn't know of any "sugar babe" who used condoms with her sugar daddy. Kader found that young women became "sugar babes" for different reasons — some so they could "put food on the table", others so they could "live the high life".

"The central story line that emerges is that within the sugar daddy relationship the 'sugar babe' is sometimes the victim, but other times the vixen," Kader said.

These women are "pushing back the anxieties around sexuality in the context of HIV and Aids" in the process of "getting not only what she needs but also what she wants".

Community beliefs

Baxen said attitudes prevalent in some communities hindered sexual education at schools. "Teachers said parents continually told them that teaching children about sex would encourage pupils to have sex at an earlier age," she told the M&G.

The words used for HIV and Aids in communities were euphemistic and derogatory because some people believed "even just saying the word invoked [the risk of catching] it", she said. "Some of the names for HIV and Aids that participants [in her research] had heard included 'the beast', 'the sickness' and 'the lotto'."

Because teachers' "personal lives always get in the way", they might not be the best people to provide the necessary education. Baxen suggested alternatives such as peer education programmes or getting "outside people" to give sexual education as part of sustainable programmes.

"Community members who not only know the children and the context but are also respected in and out of the school could be used to give lessons on sex."

The same reluctance to talk about sex that Baxen and Wood identified also served to discriminate against some pupils' sexual orientation.

Legally, schools must ensure that all children, regardless of sexual orientation, are treated equally, but many schools reinforce damaging sexual stereotypes, said Deevia Bhana, education professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

For her paper entitled Moffies, Gays, Isitabane: Learning "Straight" and the Implications for Sexuality Education, Bhana surveyed 620 schoolchildren from different race groups, mostly in grades 10 and 11 at five schools in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. She asked whether they thought teachers would support a homosexual pupil, among other questions.

A 19-year-old male pupil responded: "Gay people should be killed so that we don't have any more gay people in our country."

A 15-year-old female pupil said: "I do believe that pupils should be educated about homosexuality to change the mind-set of those who believe there is something wrong with it."

Pupils' attitudes to homosexuals were wide-ranging, Bhana told the M&G, with conservative and liberal views traversing race groups and geography. But boys showed more homophobic attitudes than girls, and pupils at schools in rural areas were more conservative than those in urban areas, she said.

"Teachers did not address same-sex sexuality, and said they did not receive any guidance about how to do so from the department of basic education," Bhana said.

The department did not respond to the questions from the M&G.

Debunking pregnancy myths at the source

"If you have sex under an umbrella, the girl won't fall pregnant," said one pupil at Barnato Park High School in Berea, Johannesburg, when asked what he had heard about sex and pregnancy from his peers.

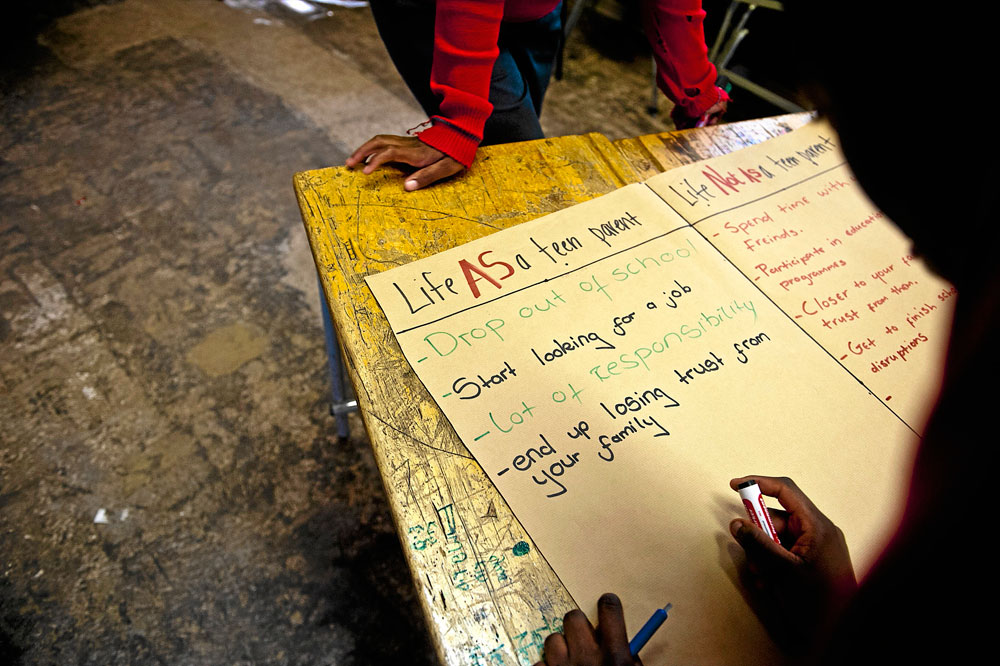

He was one of more than 200 grade nine pupils who participated last week in discussions on teenage pregnancy that the Umuzi Photo Club, a community photography project, convened at the school.

The Mail & Guardian heard the pupils sharing their beliefs about sex and pregnancy. "If the girl drinks coke after sex then she won't fall pregnant," said one.

As the pupils spoke, an Umuzi Photo Club activist listed their points on a piece of cardboard. Four matric pupils, who are also Umuzi Photo Club activists, then went down the list debunking the myths.

Grade nine pupils at Barnato High School in Hillbrow. (Delwyn Verasamy, MG)

"Guys, it doesn't matter where you're having sex, if it's in the shower or whatever, you can still fall pregnant," said one.

Many of these 14- and 15-year-olds have been exposed to urban legends about how not to get pregnant, said Carys Lavarack, co-ordinator of the project.

"We don't know how many of these pupils are actually acting on these beliefs, but the fact that they believe them is frightening," she said.

After last week's dialogues with the Barnato Park pupils, the project leaders compiled a report based on responses to a questionnaire by 100 pupils.

The pupils answered questions about the discussion, including: "What myths did you believe at the beginning of the class that you do not believe now?"

Twenty-two said they no longer believed that a girl drinking water and jumping up and down after having sex would stop her from falling pregnant, and 19 said they no longer believed that if a boy and girl have sex standing up she wouldn't fall pregnant.

Twenty-three pupils said they no longer believed that if a boy and girl have sex in water, she would not fall pregnant.

The questionnaire also asked: "In your opinion, what is the biggest challenge in solving teenage pregnancy?"

Common answers included: "Parents do not talk to their kids about sex, do not educate them," and: "Teachers saying the wrong things to pupils about sex and pregnancy." — Victoria John