Every Sunday, the elongated ebony cars brought the heavy smell of death with them. It arrived long before they reached the hospice. People who lived in the area were accustomed to it.

"For some reason our children always tended to die over weekends," Sister Kethiwe Dube recalled, twirling a pen in her hands.

Undertakers arrived cradling carrycots. The bodies of the babies, who mostly didn't make it to their first birthdays, were too small for stretchers.

"They would carry the dead girls away in pink baskets and the boys in blue ones," Dube recalled. "Lots of our staff have babies of their own, but most never use carrycots for their own kids. The memories are too ingrained."

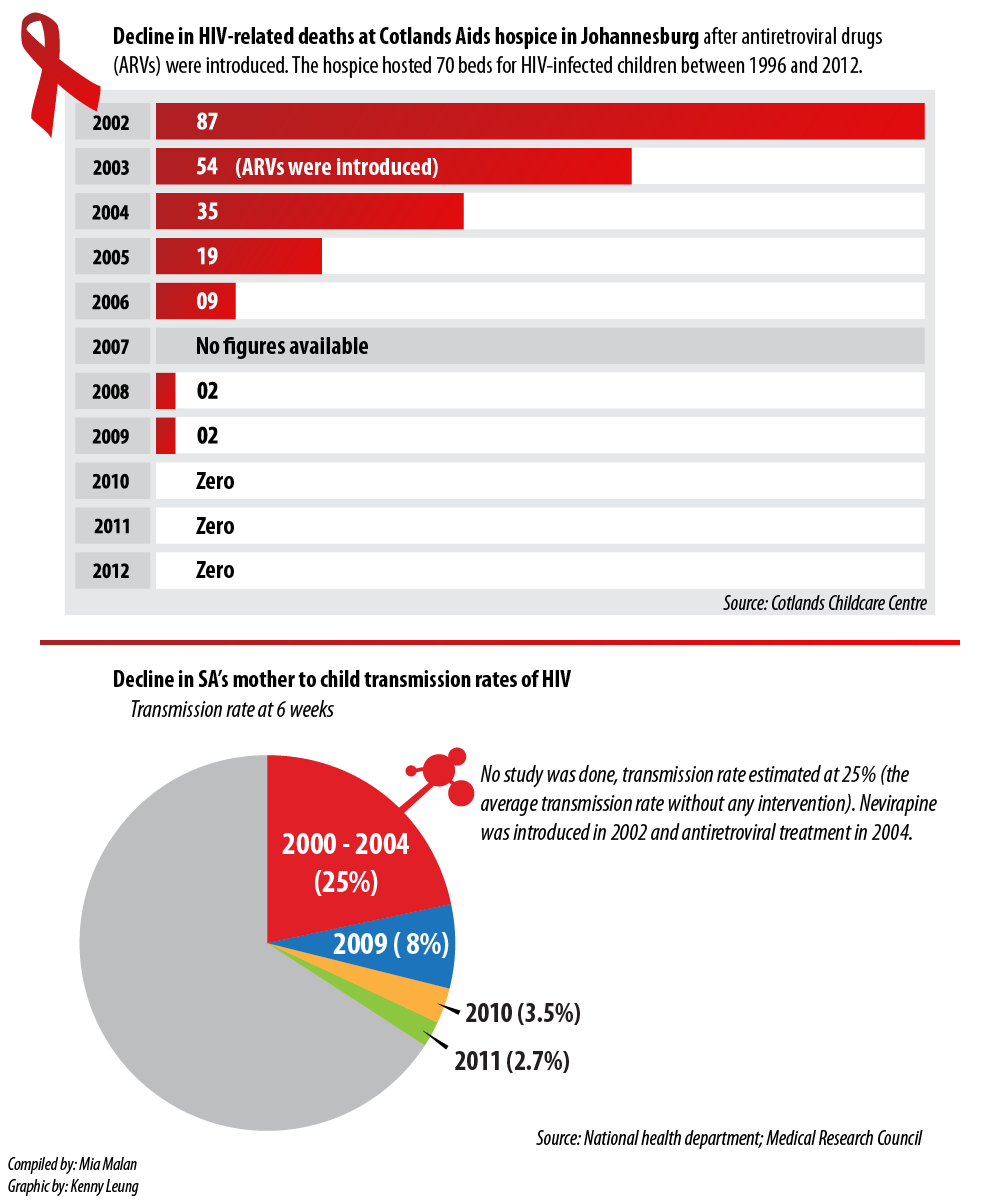

In 2002, deaths peaked at the Cotlands children's Aids hospice, with its 70-bed capacity in Turffontein, Johannesburg: 87 babies died – an average of more than seven a month. Most were cremated.

So many died between 1996 and 2003 that three memorial walls were created for them in one of Johannesburg's largest cemeteries, Westpark. During that period, other HIV-infected babies, festooned with oxygen masks, gastric tubes and drips, waited to die at the hospice.

"You'd take those children as your own and learn to love them, but you never knew if they'd be there the next day," Dube said. "It made me so anxious. It hurt. A lot. It still does."

For Dube, the "worst part" was that she could rarely hold the babies to comfort them. "Most of them had sensitive skins because HIV causes terrible skin conditions in the small ones. They would scream in pain but I couldn't pick them up because I would just cause them more pain," she said softly.

Dube often had to wear surgical gloves to protect herself against possible HIV infection when handling the children.

"I wanted to feel their skin on my skin. I wanted to love them with my bare hands. But there was always this barrier between us," she said.

Then she reached for a nearby register. Pulling it towards her, she muttered: "This is who they were … My babies …"

War to access drugs

While Dube and her babies were fighting a losing battle against death, another war was raging between South Africa's former health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang and the HIV activist group Treatment Action Campaign (TAC).

It was attempting to force the government to provide HIV-infected pregnant women and their babies with free access to the antiretroviral (ARV) drug Nevirapine. Research had proven that Nevirapine could reduce the risk of HIV transmission from mother to child by up to half.

In December 2001, the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria ordered the health department to make the drug available, but the government challenged the ruling, arguing that the judiciary had no right to determine government policy.

The baby deaths at Cotlands, and around South Africa, continued.

However, on July 5 2002, the Constitutional Court ruled in the TAC's favour and ordered the state to make Nevirapine available immediately at state facilities.

That ruling, and subsequent voluntary actions by the health department, such as to provide ARVs for free to HIV-infected people who qualified for it according to government guidelines, slowly transformed Cotlands.

"In 2006 and 2007, we started to see a visible decline in the percentage of HIV-infected babies we admitted," said Cotlands executive director Jackie Schoeman. "Prior to this, about 75% of the children staying with us were HIV positive. But that balance started to change and the proportion of HIV-negative kids we admitted started to increase."

Death rates drop dramatically

However, Schoeman said the most noticeable impact was the drop in death rates in the case of HIV-infected children.

"Because ARVs allow people with HIV to live with a chronic rather than a fatal condition, more of our kids with HIV survived. We started to buy ARVs for them in 2003, before the government provided them for free. As a result, we saw the death rate drop by 38% in one year: from 2002's 87 to 54 in 2003," she said.

By 2004, the deaths had dropped to 35, by 2005 to 19, by 2006 to nine, by 2008 to two … then, in 2010, not a single baby died at Cotlands. Since then, there hasn't been one HIV-related death at the hospice.

"It is now a rarity for us to admit an HIV-infected child and, because there were no longer enough ‘sick' HIV-infected children to sustain an Aids hospice, where children would come to die, we closed it down in December 2012," said Schoeman.

The revolution didn't happen only at Cotlands. A Medical Research Council study showed that the mother-to-child transmission rates of HIV dropped nationally from an estimated 25% in 2004 to 2.7% in 2011.

"The 2.7% rate was measured when babies were six weeks old," said Yogan Pillay, the deputy director general at the department of health. "So we still need to see if it increases when the baby is older, because of transmission through breastfeeding. But, because we now provide all pregnant HIV-infected women with ARVs throughout their pregnancy and while they breastfeed, the transmission rate at three months is unlikely to be significantly higher.

"ARVs significantly reduce the chances of a mother infecting her baby through breastfeeding and we also recommend that mothers with HIV give their babies breast milk only for six months, which further decreases the chance of transmission."

Change in focus

The implications of the drop in the number of children born with HIV and the fact that HIV-infected children are now able to live healthy lives by using ARVs also meant that Cotlands had to change its focus.

"Dying children were an emotive, tangible cause to fund. But what do you do when your cause starts to evaporate?" asked Schoeman. "We had managed to ensure that our children now lived long enough to become adults. But what's the point of longevity if you don't have the tools to become a successful adult?

"We realised we hadn't yet done anything to help them to have productive lives and that's how our new cause was born: education."

A survey that Cotlands undertook revealed that 80% of children in the Turffontein area did not start school with the "required foundational skills in literacy and numeracy", despite having attended preschools in the area.

Therefore the former hospice transformed itself into a child care centre that offers early learning development classes and facilities to children.

"We've developed a playgroup model whereby kids come to us twice a week for two hours of structured sessions. During these classes, social workers observe them to identify cases of possible abuse and a nurse offers vaccinations and TB [tuberculosis] screening," said Schoeman.

Home-based careworkers who previously visited families to offer care to those who were dying have been retrained to run educational play sessions at homes and at Cotlands. There are also several classrooms that kids and teachers from the area can use, and a toy library.

‘If we address the remedial challenges in preschool and make learning a positive experience, the children are less likely to drop out of school and less likely to perpetuate the vicious cycle of poverty," said Schoeman.

Several studies have shown that girls who don't complete their schooling are more likely to become infected with HIV, particularly in poorer areas such as Turffontein.

Dangerous neighbourhood

According a Cotlands survey, Turffontein is inhabited mainly by migrants from the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo and neighbouring African countries. The study found the neighbourhood to be "unsafe" for children; the local park was listed as "the most dangerous place in the community".

"Children live in houses that their families share with several other families. They're told to go home after school and lock themselves in their rooms for their own safety. Many children, therefore, spend excessive amounts of time watching television," Schoeman said.

Cotlands started an aftercare service that children could attend for free until their parents arrived home. There they play and volunteers help them with their homework.

For Karabo Leptisi (9), who wants to be a nurse, and Asanda Gwence (8), who is adamant she'll be a doctor one day, Cotlands is the only alternative to being locked in a room after school.

"We don't have a garden. Here we can play and there are toys and books. There's none of that at home," Asanda said, pointing at the jungle gym and the caregivers. "I learned how to read and spell here."

Latifah Khaphetshu (11), who calls herself "Queen Latifah", wants to be a "celeb" in the near future.

"The health minister visited us recently to see how we're doing. He is a celebrity. So I want to be one too," she said, adding: "We can all become what we dream of."

Cotlands assisted 11500 children and parents with education and/or counselling in 2012 and plans to reach 15000 by the end of 2013.

"The treatment of HIV has not led only to us changing our cause; it has meant that we can now help thousands of people for the same amount that it cost to keep 70 beds running for mainly HIV-infected kids," said Schoeman.

"I hope that we will be able to have a similar impact on the education sector as we've had on the health sector. We no longer want these kids to just survive. We want them to thrive."

Cotlands also offers a facility for children to stay while they await adoption.

Dube sighed: "I can now love these children with my bare hands. I can hold them and touch them."

Walls of memories

At the Westpark cemetery, the sun reached its peak in the sky on a winter's morning. Brown, dry leaves rustled softly, the sound meandering through the skeletons of the trees that guarded the graves. Birds twittered, a joyful sound that betrayed no awareness of the surrounding death.

At the rear of the graveyard, on a lawn, the three facebrick Cotlands memorial walls loomed large, and alone, near the fence of Westpark's "Jewish section" and the "stillborn section".

On one wall is the name of Thabo Mojela. He lived for three months. On another brick is the name of Nobuhle Sangweni. She drew breath for four months. Then there's the name of Tsepho Mphahlele – an "elder" – on the third wall. He died a month before his second birthday.

Since their deaths, many walls have fallen in South Africa. But for people like Dube, who once saw death by HIV every day, memory is a wall that will never crumble.

One of Cotlands' babies memorial walls in Westpark Cemetery in Johannesburg (left). Karabo Leptisi (9), Lee-Anne Monoketsi (10) and Asanda Gwence (8) (right) all attend Cotlands new aftercare centre where they are helped with homework and play freely. Photos: Skyler Reid and Madelene Cronjé

Success in preventing HIV transmission to babies marred by ARV shortages

A Medical Research Council study conducted across South Africa's nine provinces shows that the country's HIV transmission rates from infected pregnant women to their babies has dropped from an estimated 25% in 2004 to 2.7% in 2011 (see graphic above).

According to deputy health director general Yogan Pillay, this translates to 66900 fewer babies being born with HIV annually – 8100 in 2011 as opposed to 75000 in 2004. "The cost of treating a mom/baby pair in the programme is about R780 per pregnancy," Pillay said.

Research has shown that babies of HIV-infected mothers can contract the virus while in the womb, during birth or through breastfeeding.

The United Nations Programme on HIV and Aids said in report this week that South Africa had shown the second greatest decline in the rate of new HIV infections among children in seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Botswana, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia).

Studies have found that a single dose of the antiretroviral drug (ARV) Nevirapine, given to the mother during labour and to the baby after delivery, can reduce the mother-to-child transmission rate from 25% (the transmission rate during pregnancy and labour without any intervention) to close to 10%. The Constitutional Court ordered the health department to start providing this drug to HIV-infected pregnant women in 2002.

The department has subsequently expanded its programme to prevent mother-to-child infections by providing all HIV-positive pregnant mothers with a full course of antiretroviral treatment for the duration of their pregnancy as well as while they are breastfeeding, which further reduces the chances of babies contracting the virus.

Since April 1, HIV-infected pregnant women are receiving a three-in-one pill, or fixed drug combination, to make it easier for them to adhere to treatment.

"Only 40% of South African pregnant women access antenatal clinics before 20 weeks in their pregnancy, however, so some women access the treatment at a later stage than others, which results in higher transmission rates," said Pillay.

South Africa now has the largest public sector antiretroviral treatment programme in the world, with 2.1-million people on treatment. According to Pillay, 65% of HIV-infected children are being treated with antiretrovirals.

But drug shortages, particularly in rural areas, are an increasing problem. Last week, the Eastern Cape Health Crisis Action Coalition, consisting of the Rural Health Project, Section 27, the Treatment Action Campaign and Médicins Sans Frontières, reported that 28 of the 70 health facilities surveyed in the Mthatha area in the Eastern Cape ran out of HIV treatment between March and May this year.

Some hospitals and clinics received only 10% of the ARVs they had ordered from the Mthatha depot and the medicine generally arrived at clinics and hospitals about two months after it was ordered. Stock-outs were also reported in Gauteng, Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal.

Gynaecologist Coceka Mnyani from the Anova Health Institute said another challenge was the decline in international funding to support service delivery in ARV clinics. As an Anova employee, Mnyani works in public-health clinics in the field of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Her salary is paid for by funding from the United States President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief.

This funding, however, has decreased substantially and will decline further in five years' time, making it difficult for health organisations to assist the health department with staff.

"Understaffing is a constant problem in government clinics. If staff from health organisations are pulled away from the clinics, the current staff complement will have to cope with the additional workload. We need to find a way to make the government's programmes sustainable without help from outside," she said. – Mia Malan