With more talk than action, a lack of technical expertise is holding the government back from delivery and causing an exodus of engineers from the country

There may be a lot of talk about billion-rand government infrastructure projects in the wings but South African business is not smelling the cement, and the reason they say are the "blockages" in project pipelines that are delaying them.

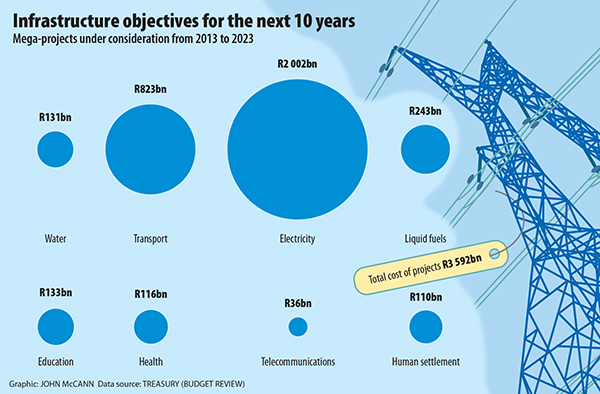

Infrastructure development, or the lack of it, is important, because it forms the centrepiece of the government's job-creation programme.

Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, in his budget review in February, acknowledged that "weakness in planning and capacity … continues to delay implementation of some projects".

But he said the government was improving its capacity to plan, procure, manage and monitor projects, and was working more closely with the private sector at different stages in the "projects' development cycle".

But industry players said that, besides a lack of capacity at government level to roll out the projects, other issues that must be addressed include corruption at municipal level, complicated and expensive tender processes, political interference, like that surrounding the Gauteng e-tolls, and labour disputes, such as those that have delayed Eskom's Medupi project.

The February budget statement highlights mega-projects that are already experiencing delays, including Eskom's Medupi and Kusile power stations and Sentech's roll-out of digital terrestrial television.

Expenditure increasing steadily

Expenditure in the public sector, including on capital expenditure and maintenance, has been increasing steadily, but a general criticism is that the money allocated for some projects is insufficient.

To the government's credit, the Presidential Infrastructure Co-ordinating Commission (PICC) has been set up, and six months ago a task team led by the treasury began meeting members of the private sector and the department of public enterprises to look at ways of attracting potential investors, like asset managers and life assurance companies.

Nicky Prins, acting chief director of the treasury's national capital projects unit, the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa (Asisa), and the Banking Association of South Africa are members of this task team.

Prins said there is "significant appetite from the private sector" but Banking Association managing director Cas Coovadia expressed the concerns of the private sector about the lack of projects and some of the reasons for the delays.

"The banks say the appetite is there, they are funding projects in different parts of Africa, but we need to see the projects come on the table sooner rather than later," Coovadia said.

"Government needs to make a decision [about a project commissioned], follow the correct procedure and stick to it, or it creates a lot of uncertainty in the market," André Smit of Asisa said.

Concerns about the delays

South Africa's big construction and engineering groups have repeatedly raised their concerns about the delays in rolling out infrastructure projects and about the spending plan outlined by the presidential commission. The delays are having a negative effect on their bottom line, they say.

Aveng, which saw its share price fall in September after announcing this year that its annual headline earnings had dropped 3% to 124.6% compared with last year, cited a slowdown in spending on infrastructure and strikes as having a major impact on productivity and profitability.

The South African Federation of Civil Engineering Contractors in July this year complained that, although work was trickling in, many of the municipal infrastructural projects that would provide them with low-cost, consistent work, such as sewerage works, water reticulation and housing, were still too slow to get off the ground.

Criticism is that the work is steeped in politics and the paperwork for tenders is cumbersome.

Coovadia said the private sector just wants to get the work done. "Just let us get in there and get our hands dirty," he said, clearly frustrated.

"I would like to see government and the private sector locked in a room where they can thrash out how best to fund these projects and get them up and going."

"No issue with policy"

He said his members have "no issue with policy", they just want to do away with uncertainty.

The infrastructure and capital project leader at Deloitte, André Pottas, said in the government's defence large capital projects by nature take a long time to get to the implementation stage, "but our planning and decision-making processes do currently take too long. There is room for capacity and process improvements to make the process shorter."

Pottas said: "The time lag for tender adjudication and the decision on appointment of a transaction adviser and contractor, and from the selection of the bidder to the conclusion of the contract is often long by international standards and leads to delays in breaking ground."

He said front end planning, feasibility studies and environmental impact assessments are important because delivery is in the construction and operations phase.

Smit, although upbeat about the task team talks with the government, said that if the government wished to see more private sector involvement in the funding of projects, there had to be certainty that projects will go ahead in the time planned.

The private sector is asking for a "pipeline" plan that will give asset managers and investment schemes a clear idea of what, and when, projects are expected to come on line.

Wrong perception

Minister of Economic Development Ebrahim Patel said the perception of "slow spending on infrastructure is flatly wrong".

"Over the last few years the PICC has helped unlock spending across more than 100 projects," he said.

Patel said more than R800-billion had been spent since 2009. Coovadia said the renewable energy project was a success story.

"Why did it work? Because there was a recognisable team co-ordinating the process and treasuring transparency and consistency of decision-making," he said.

The liquidity requirements for banks, outlined in Basel III, will mean a fundamental change in the way many of these infrastructure projects can be financed.

Basel III, a global set of rules for banks to adopt when calculating their capital and liquidity requirements, stipulates that banks must have enough cash on hand to meet their cash requirements for 30 days at a time.

Funding long-term projects

This makes it harder for banks to fund long-term projects, such as infrastructure projects.

Pottas said that infrastructure projects have relied heavily on the banks, but a broader range of funding options will now have to be considered.

"Instead of banks funding the entire 20-year project, we are likely to evolve to a model where they finance the initial stages of a project. The remaining funding will stem from project bonds or loans sold to institutional investors such as pension funds and life companies that have an appetite for long-dated assets to match their long-dated liabilities."

A popular option in Europe and the United States is an equity tranche and a short-term debt tranche.

"The equity tranche is typically funded by the project promoter and the debt piece by a bank in the construction phase, as institutional investors do not like to take construction risk," said Pottas.

"Once the project is commissioned and proven, the funding is refinanced, with an infrastructure fund taking the equity piece from the promoter."

The project bond, often listed, replaces the bank construction bridging finance and is then sold to institutional investors, such as pension funds and life companies.