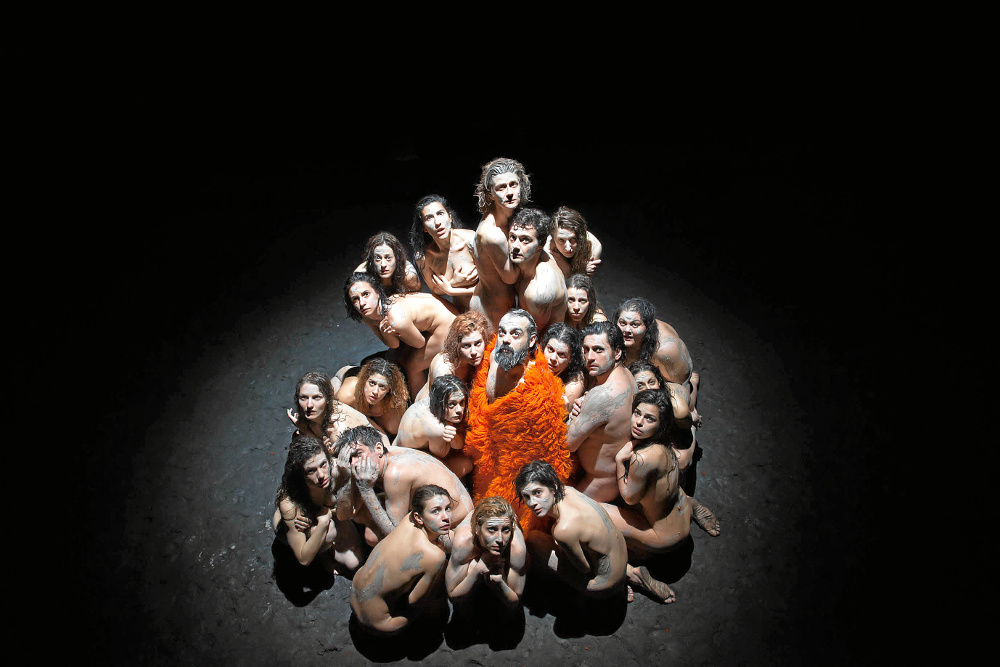

Greek tragedy: Argyris Xafis as Heracles in Women of Trachis suffers a painful death after donning a robe that transmutes into a boiling film.

Sophocles's Women of Trachis is coming to Johannesburg. Why, one asks, should anyone bother going to an archaic (more accurately, "classical", but who but the classicists will know the difference) Greek dramatic production?

It is about the death of the great hero Heracles (yes, yes, he is the same as Hercules). Surely, you may ask, he died in some vaguely heroic way, overcome by some outdated monster we have seen rehashed so many times recently on the silver screen in the flurry of Hero versus Monster epics that have been enjoying a revival?

No, actually, he dies at the hands of his wife, enveloped in a poisoned robe, writhing in agony and crying "like a girl". The story of the demise of Heracles is the story of a love triangle, of jealousy, infidelity and desperate measures. Thus it is a story that has no anchor in any particular chronological framework, social setting, age or epoch. It is as relevant in South Africa today as it was in Ancient Greece some 2 500 years ago.

The term "Greek" tragedy is used to describe what is more accurately "Athenian" tragedy, as this art form was unique to the city of Ancient Athens at a very particular time in its history. Athenian tragedy was only produced for roughly 50 years, namely the last half of the fifth century BCE, mirroring the height and decline of the Athenian Empire, which came to an end with Sparta's victory in the Peloponnesian Wars.

Tragic production was intimately connected to the political and religious life of the city and its people and reflected a self-conscious ideology of Empire and Victor resulting from victory over Persia in the Persian Wars at the end of the sixth century and resultant accrual of much more territory than had previously constituted the city-state.

Heracles struggles with being half mortal and half divine

Sophocles wrote Trachiniae, or Women of Trachis as it is translated, in the Twenties of the fifth century BCE. As a tragedian, he enjoyed great success during his lifetime. Today, he is most famous for Oedipus Tyrannos (more commonly known as Oedipus Rex), Antigone and Electra.

Trachiniae tells the story of the death of Heracles at the hands of his wife Deianeira. As fascinating as the story is, it is one of the least known stories about Heracles except to those with a special interest in mythology or the classics.

In the popular imagination, Heracles is the monster slayer, son of Zeus and the mortal princess Alcmene. Heracles is the hero who performs the 12 impossible tasks imposed on him by King Eurystheus.

Few know that these tasks were imposed as a penance for the murder of his first wife and children in a fit of madness visited upon him by Hera, Zeus's wife and queen of the Olympian gods.

Few know that, like many Greek heroes, Heracles's deeds and behaviour are less than praiseworthy. Indeed, the "real" Heracles, if any mythological hero can be so-called, is a complex one whose external battles may be read as the manifest forces of internal darkness and chaos as he struggles to come to terms with his divided nature as half mortal and half divine. As with many heroes, his dual nature is essentially irreconcilable, reflecting the essential unbridgeable differences between the mortal and divine planes.

This is the "man" Deianeira gets or, more accurately, "wins" for a husband. Initially grateful to him for saving her from the terrifying alternative – the shape-shifting river god Achelous – Deianeira soon learns how lonely is the day-to-day existence of a saviour hero's wife.

Once she has borne Heracles a son, Hyllus, she finds herself exiled and alone, far from her native home in Trachis, and rumours of her husband's feats keep her fearful and sleepless.

She describes herself as an outlying field that Heracles visits to sow on rare occasions. The traditional metaphor she uses reveals much about Deianeira's self-image: she sees herself as embodying the image of the faithful wife who waits at home, whose duty is to bear children and keep the household in order.

A scene from Women of Trachis.Photogragh by Patroklos Skafidas

A scene from Women of Trachis.Photogragh by Patroklos Skafidas

A prophesy about Heracles

The play opens under the auspices of an oracle inscribed on a stone tablet that Heracles had given to his wife for safekeeping. The oracle seems to state that the end of the hero's labours is drawing to a close.

While Deianeira dares to hope that this could mean Heracles's imminent return to her, she hears the news that he has indeed just finished sacking a great city and is making preparations to return. He sends ahead the booty he has plundered from the city while he prepares to purify himself and sacrifice to Zeus his father.

As first prize in a long train of riches and plunder and captive slave women is the Princess Iole, spear-won bride of Heracles, daughter of the fallen King Iolus. She arrives, younger and more beautiful than the now ageing Deianeira, her very presence threatening to weaken the already tenuous grip the lonely wife has had on the affections of the great man.

As important as the character of Iole is, being the catalyst that sets the ineluctable events in motion, she remains silent – a tragic convention that is visually powerful and evocative of the prophetess Cassandra, who arrives in Aeschylus's play (Agamemnon) in a similar fashion.

The cursed love charm

It is the intrusion of the captive human prize that changes everything: patient, and hitherto long-suffering, Deianeira is galvanised into retaliating by sending Heracles a gift of her own, "in return for the gifts given". She brings out an elaborately embroidered robe, woven by her own hand, intended for her husband to perform ritual sacrifice in.

She makes a bold decision to anoint the robe with what she believes to be a powerful love charm in the desperate hope that it will re-secure her husband's affections.

The love charm has a dark history – the story of its procurement and employment is one that tells a further tale of revenge, rivalry, prophecy and of the guilt or innocence of Deianeira regarding the role she played in bringing about the death of her husband.

When Heracles dons the elaborate robe and approaches the sacrificial flames, we are told how the fabric of the robe transmutes into a boiling film that clings to his skin and eats into his flesh, causing the onset of his slow and agonising death. It seems as if the love charm has malfunctioned.

This brings us only two-thirds of the way through the play, which continues for another 460-odd lines during which Deianeira's guilt is confessed in a scene of wordless, almost ritualised suicide, and a bizarre arrangement is made between the dying hero and his son that ensures his object of plunder is appropriately handed down from father to son.

Those more familiar with the mechanisms of Athenian tragedy will know that the events of this drama were not innovations of Sophocles. Indeed, the material for these plays was hundreds of years old, inherited from a far older oral tradition dating back to Homer and Hesiod. It was the treatment of these stories, familiar to the audiences, which marked the genius of the playwright, and in this play Sophocles's true genius reveals itself particularly in the multiple interpretations one is able to extract from the action.

The Women of Trachis seems to allow for many readings: Deianeira sends Heracles a robe, woven by her own hands, anointed with what she believes to be a love charm in a desperate attempt to regain his love and win him back from Iole; or Deianeira sends Heracles a robe, woven by her hands, anointed with a substance she knows to be a deadly poison hoping to secure his death by guile, in order to punish him for attempting to replace her with Iole; or Deianeira sends Heracles a robe, woven by her hands, anointed with what she knows to be a deadly poison but in the hope that its correct dosage and application will have the effect of a love charm to regain the heart of her husband.

The author Christopher Faraone makes a compelling argument for the last scenario in Deianeira's Mistake and the Demise of Heracles: Erotic Magic in Sophocles's Trachiniae, Helios 21, 1994.

Andrea Doyle is the chair of the department of Greek and Latin studies, faculty of humanities, University of Johannesburg

A director’s instant classic?

Thomas Moschopoulos, an internationally renowned director of opera and theatre, directed Women of Trachis with the National Theatre of Greece for the Epidaurus Festival in Greece last year. It was filmed under his supervision and, with his permission, is being screened for two nights only at the University of Johannesburg Theatre under the auspices of the university's Greek and Latin studies department and the Greek embassy.

Moschopoulos, who is being brought over by the embassy, will introduce the play at both screenings on February 21 and 22.

His staging of Sophocles's Elektra at the Toronto Stratford Shakespeare Festival in 2012 was widely acclaimed.

He will also be holding workshops at the University of the Witwatersrand drama school on February 18 and 19 as well as a morning of seminars at the UJ Theatre on February 20.

For bookings and more information, contact Natasha at [email protected] or Barbara at [email protected].