When Jeremy Acton feels a cold coming on, he says he regularly stops it in its tracks. “I smoke a joint of dagga and, mostly, half an hour later, there’s no flu. Sorted.”

If the cannabis does not deter the sickness, he lights a joint and allows the smoke to cover his “snotty nose and throat area”, or he drinks “dagga tea” mixed with ginger and chilli. “It opens up my chest, reduces the fever and pain from the flu and the chilli makes my nose run, which helps to get the bugs out.”

But, mainly, Acton believes that “prevention is better than cure”.

“People over the age of 21 should be smoking dagga moderately. I’d say between four and 12 joints a day, to prevent all those ailments from happening or to slow them down from arriving, including cancer,” he says.

Earlier this month, Acton helped a woman in her 80s who is in the advanced stages of womb cancer to produce cannabis oil illegally by providing her with the cannabis and the recipe, so she could make it at home.

“A state hospital told her she was too old for chemotherapy so she decided to take as much of the oil [orally] as she could for three weeks, until her next scan, so that we could see if it’s made a difference to the progression of the cancer,” Acton explains.

“The law is at fault, not me. I don’t care a shit if I get arrested anymore; I’m merely claiming my constitutional right to act in compassion and according to my conscience. We’ll know the results of the scan next week.”

Believer

Acton is 50 and has been smoking about eight joints a day since he was 24. He lives in Durbanville, north of Cape Town, in a middle-class townhouse complex with a “small pool”, along with his daughter (9) and partner. The mother of his child doesn’t approve of his cannabis use.

“The smell freaks her out so I only smoke outside, and I take care to ensure the smoke is blowing away from my neighbours,” he says.

That Acton approves of cannabis is clear. He is, after all, the leader of the Dagga Party, which hopes to get 10 representatives – all cannabis smokers – into Parliament or provincial legislatures after this year’s elections.

“The neighbours know about me and my dagga because I regularly wear my Daggaboer [cannabis farmer] T-shirt, which I designed myself,” he laughs.

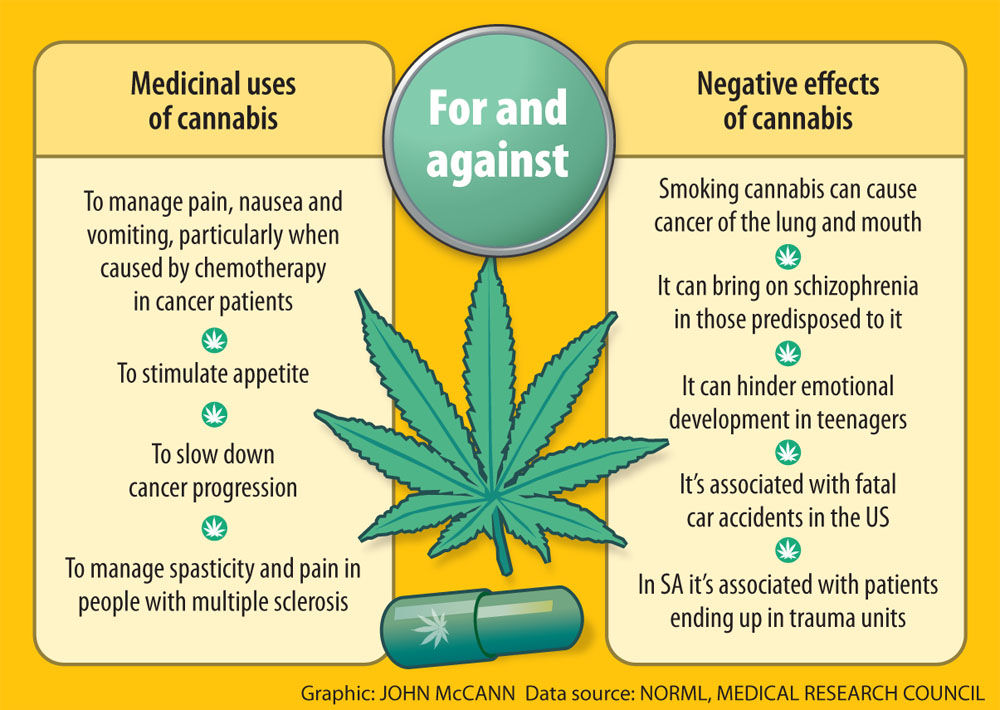

Medical research has shown, however, that although the cannabis plant might have several promising attributes that could be used in the management of pain, nausea, spasticity and vomiting, smoking the plant is not healthy.

Health risk

“There are studies which have shown cannabis smoking is up to eight times more likely to lead to lung and mouth cancer, as well as diseases such as bronchitis and emphysema,” says Stellenbosch University toxicologist Gerbus Muller. “It would be naive to think that smoking dagga is good for your lungs.”

But Acton remains adamant: “The studies are plain rubbish. Dagga cures cancer – it doesn’t cause it.”

There is indeed research that has shown a link between cannabis and a positive effect on cancer, says Charles Parry from the Medical Research Council (MRC), but the studies are in an “elementary stage”.

It’s still at the cellular level, and animal studies have also been conducted, but a sufficient number of human trials, which are generally needed before a medicine can be approved by a medicine’s control council, have not been done. It’s possible that cannabis can have an effect on cancer, but perhaps people are running ahead of the evidence.”

Most preliminary studies have been conducted with extracts of some of the main active ingredients of cannabis – the cannabis itself was not smoked.

“When you have a medicine, you want it to be stable, so everyone gets the same amount every time,” Parry says. “If you’re smoking dagga, you’re not all going to get the same amount because plants and the sizes of zols [joints] differ.”

Medicinal use

Last week IFP MP Mario Oriani-Ambrosini, who has late-stage lung cancer, made a passionate plea in Parliament for the legalising the medicinal use of cannabis by tabling a medical innovation Bill.

The MP had not been smoking cannabis either: he has been using cannabis oil suppositories (illegally) for pain relief. He believes the oil has enabled him to survive his cancer so far.

According to Parry, given the gaps in human trials, it is “not clear that we can recommend moving ahead with legalising the medical use of cannabis at this time.

There seems to be a substantial disconnect between the therapeutic use of cannabis by Oriani-Ambrosini and others and solid research on the risks and benefits of such use”.

But Ambrosini’s speech was met with a standing ovation from Parliament, an indication that the government is open to change.

Compassionate response

Lindiwe Sisulu, the minister of public service and administration, said she was pained to see his state. “I had a word with the minister of health and he indicated to me we are really keen to follow up on the discussion and research around the world on the issue of the potential of decriminalising medical marijuana. We are a caring society.”

But the MP’s appeal was not unique. According to Parry, at least 10 countries, including Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain, have legalised the medical use of cannabis.

Twenty American states have done so too, with Colorado becoming the first state to legalise the recreational use of cannabis in 2012. Retail “weed” is taxed at 25%, making it one of the most heavily taxed consumer products in Colorado. People aged 21 years or older can buy up to 28.3g from a licensed cannabis store.

According to the organisation, NORML, which advocates for the legalisation of cannabis, medical users, with a written doctor’s recommendation, don’t face the 25% additional taxes and may possess 56.6g, which is twice the normally allowed quantity of cannabis. They’re allowed to cultivate six cannabis plants in a private space. Conditions for which doctors can recommend cannabis include cancer, chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, HIV and nausea, among others.

Cannabis regulations

Section 7 in Ambrosini’s Bill suggests that “no one shall be liable or guilty of any offence for growing, processing, distributing, using, prescribing, advertising or otherwise dealing with or promoting cannabinoids for the purposes of treatment and commercial or industrial uses identified by the minister of trade and industry”.

According to the Cancer Association of South Africa’s head of research, Carl Albrecht, this is “extremely concerning, because if you look carefully, they want to decriminalise dagga use across the board … It seems that anybody would be able to grow dagga, process it and advertise it if it’s for treatment. How do you police whether it’s for treatment or not? And treatment of what?”

Parry says, following the tabling of Ambrosini’s Bill, the MRC has been approached by people, including a medical doctor, who want to obtain licences to be “involved in growing cannabis, because they think the government is about to start a big project”.

Neil Kirby, from Werksman’s law firm, says the “policing” of cannabis use and production will be essential, but costly. “If one has a system that is largely uncontrolled it would mean that almost anyone could have access to cannabis for any ailment whatsoever. And if that is so, do we want a society where there is an existing drug problem, which may be exacerbated by a well-intended law?”

Recreational use

The recreational use of cannabis has negative effects, according to certain studies. A study, published in last month’s American Journal of Epidemiology, found that “drugged driving, specifically under the influence of cannibis and narcotics, may be playing an increasing role in fatal motor-vehicle crashes”.

An MRC study detected cannabis in 58% of Cape Town-based patients who ended up in trauma units. “It suggests that cannabis increases someone’s risk of ending up in a trauma unit, because it might have impaired someone cognitively,” says Parry.

He says we should rather learn a lesson from morphine (the main psychoactive chemical in opium). It also started as a plant derivative (from the poppy plant) that wrecked society when it was used as an “opioid analgesic recreational drug” until it was legislated as a heavily regulated Schedule 6 medicine. “We tend to say, ‘cannabis is a harmful substance, it can’t be used at all’, whereas we use substances like morphine on patients for pain management.”

The Dagga Party’s Acton hops on a minibus taxi every 10 or so days for a 20-minute ride to the township of Delft, where he pays R50 for 80g of “good Transkei weed”.

Acton insists he has “the constitutional right” to his beliefs. “And besides, at R1 a zol, dagga’s cheaper than cigarettes – and I don’t have to pay VAT.”

[This piece was originally published on February 28 2014.

Tell us what you think – make a comment and rate our story on a scale of 1 (really bad) to 10 (excellent). We’d love to hear from you.