"She is such a gifted child," the teacher gushes. "She reads the Bible and she preaches like hell." The teacher pauses, then smiles.

"When she preaches, the devil knows that it's time to run out. And when she sings, the heavens open up!"

Oblivious to the excitement going on around her, Dembe Ndou (14) is standing in front of the half-length mirror hanging on one of the walls in her classroom, running a purple comb through her short hair.

Her teacher scurries around the five desks facing one another at the opposite end of the room, trying to get the rest of Ndou's classmates to settle down. One boy is restlessly rolling around on the carpeted section of the classroom.

The teacher's anxious efforts go almost unnoticed, except for one boy who asks: "Ma'am, uyo shay' ichoir?" (Ma'am, is she going to play choir?)

"Yes!" she answers enthusiastically. "Now let’s all keep quiet and listen."

A hush falls over the classroom. Straightening out her black school blazer, Ndou takes a seat in front of the keyboard, flanked by a set of oversized speakers. After laboriously fiddling with the settings of her instrument, she patiently adjusts the microphone in front of her. She starts playing and the speakers boom loudly as she belts out a hymn. Her classmates sway back and forth to her singing, some clapping unco-ordinatedly while others sing along.

'She sings very well'

Her song is simple: "We lift Him higher, higher, higher. When the praises go up, His glory comes down."

Dembe continues to play the keyboard as her song reaches a crescendo; her eyes are closed.

"She sings very well. But the strange thing is that she has a speech problem, you cannot communicate with her. When she speaks she doesn't pronounce some words correctly, but when it comes to singing she is perfect," says Dembe's father, Maanda Ndou, with a wistful look in his eyes.

Dembe was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in 2004 and has since been a pupil at Usizo Lwethu Special School in Daveyton on the East Rand. Autism spectrum disorder is a "complex disability that occurs because of a difference in brain development and functioning", says Sandy Klopper, head of Autism South Africa, a nongovernmental organisation that works with those affected by the condition.

"The spectrum is huge. On one side of the spectrum you'll have individuals that will never learn to communicate and who have real difficulty making sense of the world, and will be dependent on support for the rest of their lives," she says. "And then at the other end of the spectrum you have individuals that are just slightly affected and will lead independent lives – then of course you have everything else in between."

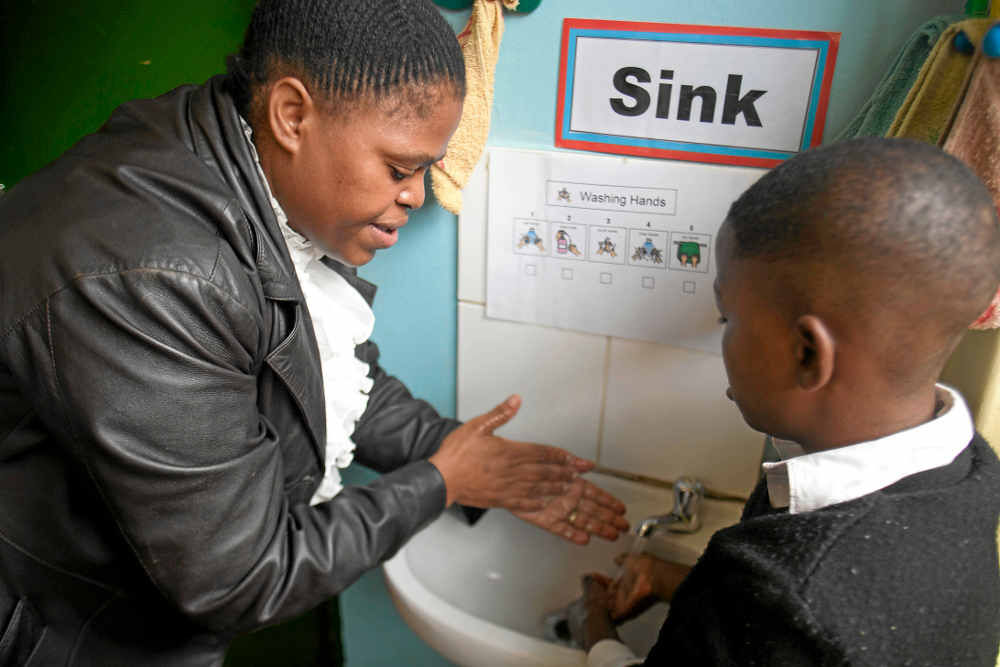

Thabile Mphogo helps a pupil to wash his hands. (Oupa Nkosi)

Once a month the organisation runs an autism assessment clinic where parents from disadvantaged areas can have their children evaluated by some of the country's top neurodevelopmental specialists, along with teachers and therapists.

"Autism is a disorder of social communication, so that’s the main disability that these children have. They can’t communicate and communication is obviously more than just speaking; it's nonverbal communication as well as eye contact and so on," says neurodevelopmental paediatrician Lorna Jacklin, who heads the neurodevelopmental clinic at Charlotte Maxeke Hospital in Johannesburg and works closely with Autism South Africa.

"People with autism also struggle with social interaction and don’t make friends easily. They actually struggle with social empathy and they don't relate to people on a social level. It doesn't mean that they don't relate at all, it means that they don't relate like other people relate.

"They also have what we call astereotypical behaviour, which might be hand flipping, or it might be behaviours like lining things up, or excessive collection of things," says Jacklin.

Dembe's mother, Rendani Makhado, already knew her child was different when Dembe was only a toddler. "She couldn’t speak [like other children], she only started saying words at the age of four," says Makhado.

But they had no idea exactly what she was suffering from. "We took her to many different specialists and therapists, but they couldn't tell us exactly what was wrong with her. They only said that she had a speech problem," Makhado recalls.

Very talented

Her parents say they realised early on that, despite her disability, their daughter was very talented. They enrolled her in Usizo Lwethu Special School, a school for children with disabilities, in 2004. It wasn’t until the school opened separate classes for children with autism that they learned that Dembe was autistic – before that, children with autism were taught in the same class as children with other intellectual disabilities.

"Parents often have that gut feeling that there’s something different, or something wrong with their child. And they are literally sent from pillar to post with doctors just not understanding what autism is," says Klopper.

Parents are often turned away by doctors who tell them that "boys develop slower than girls" and their child will outgrow the problem. This, according to Klopper, is largely because autism affects a child's communication, social behaviour and sensory processing, and this sometimes translates into problem behaviour because the child doesn’t have the tools to communicate their needs in a socially acceptable manner. So often a child will be diagnosed with a behavioural, (or in Dembe’s case, a speech problem) instead of autism.

Jacklin says that diagnosing autism depends a lot on the child and how they are affected by the disability – in "high-functioning children", who are usually very intelligent and present with "mild behavioural problems", it’s often difficult to diagnose autism.

“Generally about 50% of the children [with autism] are intellectually disabled and some of them are severely intellectually disabled. So then you have to determine whether the child is really autistic or if it is just an intellectual disability,” she says.

"So at the two ends [of the autism spectrum], there are the very intelligent children and there are the very intellectually disabled, so it becomes more difficult to make a diagnosis. Those in the middle [of the spectrum] are easier to diagnose."

Although the exact number of people affected by autism in South Africa is not known, a study this year by the United States government’s Centres for Disease Control found that one in every 68 children in the US is affected by autism.

"So if we look at our birth rate in South Africa, every 45 minutes a child that will develop autism is born," says Klopper.

'Genetic predisposition'

Jacklin and her colleagues see around 80 children a month at the clinic for autistic children at Charlotte Maxeke Hospital in Johannesburg – but no one really knows what causes it.

"There seems to be a genetic predisposition which is triggered by environmental factors, although no one can as yet identify these specific factors. Nobody can put their finger on exactly why it happens," says Klopper.

Autism is under-diagnosed, partly because South Africa has very few doctors qualified to diagnose the condition. Specially trained paediatricians, paediatric neurologists, psychiatrists and neurodevelopmental specialists can diagnose autism. There are only nine neurodevelopmental paediatricians in the country. Jacklin says that South Africa only produces two neurodevelopmental specialists a year.

Autism can be misdiagnosed if a medical practitioner is not specifically trained in diagnosis. A neurodevelopmental paediatrician is equipped with the specialist knowledge to ensure differential diagnosis.

"Making a diagnosis is a team effort. It is doctors who are expected to make a diagnosis. But the input from occupational and speech therapists clearly define the challenges a child faces and informs the doctor’s diagnosis," Klopper says.

Early diagnosis and intervention is essential to help improve the quality of life of children with autism, she says. "There are plenty of stories of how a child starts with high support needs and then, with intervention, improves so that they can function in society in a meaningful way."

Specialist educator Naomi Crous says, however, "many times they are only diagnosed when they are six or seven years old, because often parents are in denial that there's something wrong [with their children]. It is only when children go to school and the teachers pick up something [is not right] that they are referred for more tests."

Crous works for the Children's Disability Centre, a nongovernmental organisation started by Jacklin that trains teachers of children with special needs and provides support for parents with disabled children.

"Children with autism need a specific intervention and a specific way in how they are taught in the classroom, but there aren’t a lot of public schools that specialise in autism," says Klopper.

"A lot of schools are trying to develop autism units that are part of the main school. But unfortunately most of our [autistic] children are actually in school."

Mmatseleng Magane teaches pupils about the weather. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Usizo Lwethu, Dembe's school, is nothing like a "normal" school; instead of science and literature, the curriculum consists of basic life skills such as personal hygiene, and vocational training such as sewing and cooking. Unlike in their community, here the pupils are not seen as "abnormal" or "crazy".

"My sister’s child has autism so I have always been aware of this condition," one teacher says. "But people in the community call this the crazy school. Sometimes they will say stuff like 'you are starting to act like those crazies you teach'."

Klopper says this type of attitude is part of the "misunderstanding and a lack of awareness of what autism is". People stigmatise children with autism, she says. They think such children have behavioural difficulties when in fact they battle with communication and processing sensations such as touch.

"Some of our children have sensory difficulties and communication difficulties. You can imagine if you have a child who is very tactile defensive but he's unable to tell you that when you hug him it hurts – not that it's just a preference, but it literally hurts.

"If they are unable to tell you that, they will start developing behaviour [to show how they feel] like 'I don't have the words to tell you, so I might just push you away'."

'Punishment from the ancestors'

She says that in rural areas children with autism are perceived to be "a punishment from the ancestors or that it looks like they are hallucinating because they often cover their ears, or that they are talking to themselves.

"Often when our children are covering their ears it's because there is a sound or noise in their environment that is overwhelming them. But it appears to somebody who doesn't understand autism that they are kind of possessed or that they are talking to demons."

This was not the case for Dembe, however, whose parents decided at an early stage that "keeping her at home will not help us, so that little improvement that she will gain [at school] is better than nothing".

"Now she can read the Bible and she can read English," says her proud mother.

Dembe is as popular in her community as she is at school. "People are only interested in her singing. They don’t care about her disability. Even our extended family is starting to take note of her talent," says her father excitedly.

Back at Usizo Lwethu it's break time. The classroom is packed with spectators – teachers and other pupils have abandoned their lunches to watch Dembe perform. And she doesn't disappoint.

Seemingly oblivious to her audience, she drums hard on the keys of her instrument. This time she sings a lively gospel tune that sends the crowded classroom into a gyrating frenzy. Teachers and students jump up and down while others sing along with their hands waving in the air.

Dembe's musical talent is strongly supported by her parents. Her father bought her a keyboard when she was just nine years old.

"She taught herself how to play it within four months," says Makhado with a proud smile. "Our church doesn't have a keyboard so Dembe takes her own and plays during service every Sunday, and she sings in the worship team [choir]."

For the soft-spoken man and his wife, their eldest daughter is heaven-sent. “When she was born it was difficult [to accept her condition]. I would even ask myself why.

"But you can see that she is not an ordinary child. I just wish that the whole world can see her talents, and that she becomes everything that God has designed her to be," says Maanda Ndou.

A pupil makes beadwork at Usizo Lwethu Special School in Daveyton. The school teaches those who are mentally disabled skills such as learning how to sew to help them to become self-sufficient.

Warning signs of autism

- No babbling by 11 to 12 months of age;

- Odd or repetitive ways of moving fingers or hands;

- Oversensitivity to certain textures, sounds or lights;

- Compulsions or rituals (has to perform activities in a specific way or sequence);

- Preoccupation with unusual interests, such as light switches, doors, fans, wheels;

- Doesn’t play normal baby games such as peek-a-boo;

- Doesn't point to show things he or she is interested in;

- Doesn’t play with toys in the same way other children do. A little boy who is not affected by autism will put a toy car down and play with it whereas a child with autism may, for instance, turn the car upside down and focus on spinning the wheels – they don’t use their imagination and become creative with play;

- Struggle to make friends; and

- Rarely smile or make eye contact when interacting with people. – Source: Autism SA