There is not much of a view from Vijay Kumar's home near Shadipur depot, west Delhi. He lives in one of the most deprived slums in the Indian capital, in a square mile of narrow lanes, teetering brick tenement homes and open sewers shared by 15 000 people. Yet Kumar's ambitions have never been restricted by his circumstances.

Kumar (22) is studying for exams for entry to the prestigious Indian Administrative Service – at least when there is power to run a light in the two rooms he shares with his parents and siblings. There are only 4 500 of these elite bureaucrats, and just a hundred or so new recruits each year.

Kumar will be among up to 500 000 candidates. "I want to be in the system and from within do something for my community and for my country," he says. "To change things you need power. I am not interested in money but in doing something for India. This is the responsibility of my generation."

Over the next six weeks more than half a billion Indians will go to 930 000 polling stations in the 16th general election since the country won independence from Britain in 1947. The impact of the 120-million first-time voters is hotly debated, but what is undisputed is that Kumar's generation will decide their nation's future.

First there are the demographics: a third of the population is under 15, more than half under 24; every third person in an Indian city is aged between 15 and 32; the median age in India is 27.

Then there is the wider story of present-day India: the growth that boosted incomes and reduced poverty has faltered in recent years.

Time of uncertainty

Traditional values and customs have given way to uncertainty. Much is changing, and the process of transition is traumatic for millions. India's youth could be a "demographic dividend", ensuring prosperity for decades to come – or a disaster, condemning the country to years of deep social tensions.

For, as a recent report by the United Nations commented, if there is a "vibrancy" among young people, there is great anger too.

In part, this is provoked by the challenges that Kumar and people like him face in their search for a better life for both themselves and for others.

Shamsher Singh hopes the new government will provide more job opportunities

for the youth. (Reuters)

Educational institutions are over-subscribed and under-resourced. Worse, perhaps, there is little guarantee of satisfactory employment whatever the investment of time and money. According to Indian government data, although growth averaged 8.7% from 2005 to 2010, only a million jobs were created, leaving 59-million new entrants to the labour market with nothing.

That is what worries Saklan Shukla (19), who spends six hours on a crowded bus every day to get to his college in Delhi to study computer science. "The biggest problem is there are no graduate jobs. And I have to travel so far to find a good college that is affordable."

Graduate unemployment can reach 30% for women in rural areas. Even for men in towns, it is at least 17%. Javed Khan, from the north-western city of Meerut, described the "tension in the mind" that results. "A good job is a very hard thing to have. Maybe a government job is best. But for that you need to be knowing someone," said Khan (20).

Basic public services

In the cities or towns, such stress is exacerbated by the failure of authorities to provide even basic public services – power cuts are common.

Potable water is rare. Food prices are rising, so are rents. Bribes have to be paid for school and college places, to the police, to petty officials to ensure they perform basic administrative tasks, even for hospital beds. If you have connections – to a doctor, a head teacher, a top bureaucrat, a police officer or, best of all, a politician – life can be much easier. But without, it is a struggle.

There is also violence. As elsewhere in the world, 18 to 25-year-olds in India are disproportionate victims, and perpetrators, of violence.

So-called "honour killing" does not just involve parents, but siblings too.

Young women living more independent lives than their mothers suffer systematic sexual harassment, and sometimes assault, in public and, increasingly, in the workplace.

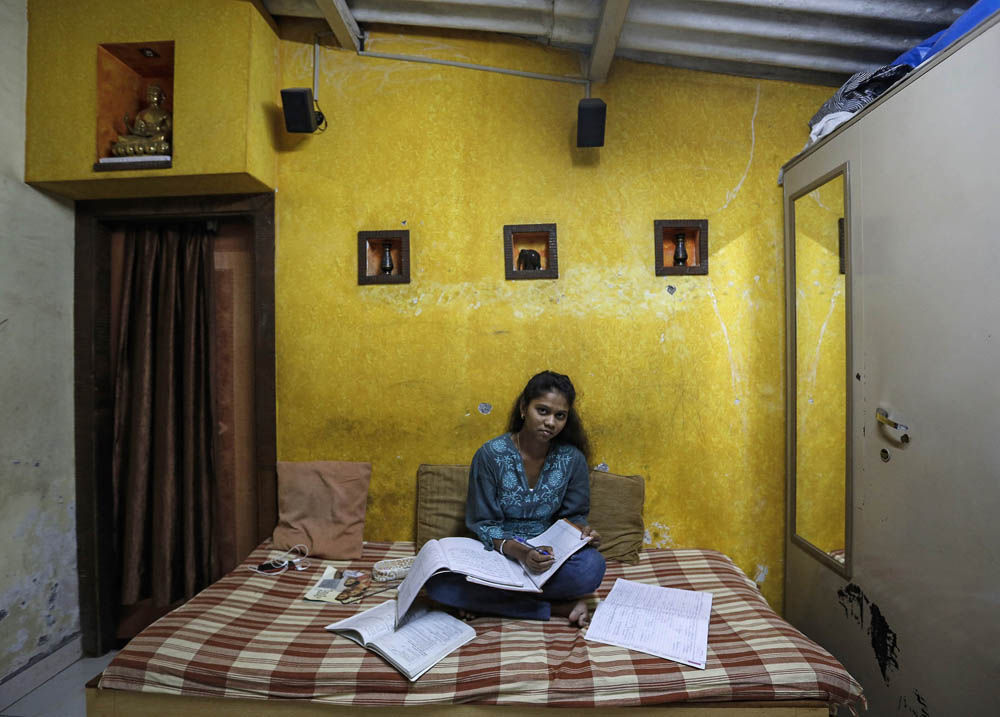

Riteesha Tambe wants a better higher education after the extended elections. (Reuters)

But young people say their generation is no longer prepared to accept their circumstances – and that alone is a major change. "I know hate is a strong word. But I hate people who sit at home and in an office and complain about the country. If we want change, then action is the only way forward," said Palak Muchhal (21) from Indore in Madhya Pradesh.

Muchhal, a professional singer, has raised more than 37-million rupees (about R6.3-million) to save the lives of more than 550 children with heart ailments. "I have a gift and I want to use it for the betterment of people around me. I feel blessed."

Others, too – from a young Kashmiri woman who invented an Android app that acts as a directory of all the important and often unobtainable government numbers in the state to a student who started a nongovernmental organisation connecting donors and charities – are active in guiding the transformation of this varied and complex country.

There are people such as Jason Temasfieldt (26), a former event organiser who launched a campaign against harassment of women in India's commercial capital of Mumbai after his cousin was stabbed to death while intervening to try to protect a female friend. He said the tragedy made him realise he could no longer turn his back on people in trouble and needed to get involved through social activism.

"I'm not alone. There's been a tremendous change in recent years. Once we were not bothered by what is happening around us. Now we are, and I can see some big change that is going to come in the future."

High expectations

Even in the slum that was home to the men who gang-raped and murdered a 23-year-old physiotherapist in Delhi in 2012 – an event that prompted tens of thousands of youngsters to take to the streets – young people have high expectations of life. Young women talk about being fashion designers, doctors and scientists. Their male counterparts are less ambitious, or perhaps more realistic, but still hope for something better.

"I could start as a rickshaw driver, like my dad, but then invest my savings and start a taxi business. Eventually, if I work hard, I can move out of here and be earning some real wealth," said Rakesh Singh (21).

Sameer expects food prices to go down. He is among more than 100-million newly

registered voters. (Reuters)

Perhaps the greatest challenge for India's often elderly policymakers lies in managing expectations.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta, president of the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research think-tank, says it is unlikely that young voters would vote as a bloc.

"A lot of the old historical examples by which the parties used to discredit each other, probably for good or bad, no longer have any resonance," Mehta told the local Mint newspaper. "Memories of the Emergency [a period of unrest in the mid-1970s], 1984 [anti-Sikh riots], all of that, which in a sense defined that ideological space, perhaps even around secularism and so forth, are not very big for these kids."

Party promises

This explains why senior Bharatiya Janata party officials believe their party's message of economic reform and decisive leadership will appeal to a widespread desire for both solutions and "empowerment".

Congress party strategists said their campaign leader Rahul Gandhi's relative youth – the scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty is 43 – and their tradition of "pluralist secularism" will win over young people. Many young people are expected to vote for the Aam Aadmi party, formed in 2012 to combat corruption and present a new, transparent, accountable alternative to the established political groups.

The election commission, which hopes to see a turnout of more than 70% in the polls, has been trying to motivate the young to vote. In the capital, registered voters have increased in four months from 11.9-million to 12.7-million, with roughly 42% of the newly enrolled voters in the 18-19 age group.

But some experts downplay the likelihood of any "youth revolution".

"There are some signs of a greater interest in politics compared with the past, but it's marginal. There's a lot of euphoria but any difference from the last election is likely to be purely demographic," said Professor Sanjay Kumar, of the Centre for Developing Societies, Delhi. "At the very least there appears to be no sign of a lot of tension. That gives hope." – © Guardian News & Media 2014