Former president Thabo Mbeki's presidential library is intended to give context to issues that characterised his term in office.

“Thabo Mbeki built a library so large and so complex only he could navigate it”, writes author Stacy Hardy in A brief history of presidential libraries.

She writes of Mbeki’s ability to carry his books in his head, a library as “reliable as the great archives of France, the United Kingdom and Russia”.

Former president Thabo Mbeki’s presidential library will be constructed in three phases: the first is a miniature library in the Kgorong Building at Unisa Muckleneuk campus. The second phase involves the Unisa main library and is expected to open next year. The third phase will be the establishment of a facility to house the expanded library and museum.

This week, reporters were shown around a “prototype” of the library on the first floor of Kgorong building on Unisa’s main campus.

Dr Buhle Mbambo-Thata, the executive director and curator of the Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library, or TMPL, said: “TMPL [which she pronounced “temple”] is not a shrine for Thabo Mbeki but a place for us to share ideas, a living library to preserve the presence of the man.”

Mbambo-Thata said the library was launched in September to commemorate heritage month and to celebrate Steve Bantu Biko, whose anniversary was four days before the launch.

‘This is where he can tell his story’

Mbeki’s presidency was marked by HIV and Aids denialism, neoliberal economic policies and his “quiet diplomacy” on Zimbabwe. With the establishment of the library, Mbeki wishes to place his political work within a larger context.

Mbambo-Thata said: “We want to provide a space to reflect on the processes and realities which have created the conditions where Africa is today and to be able to confront the question: Where should Africa be tomorrow?”

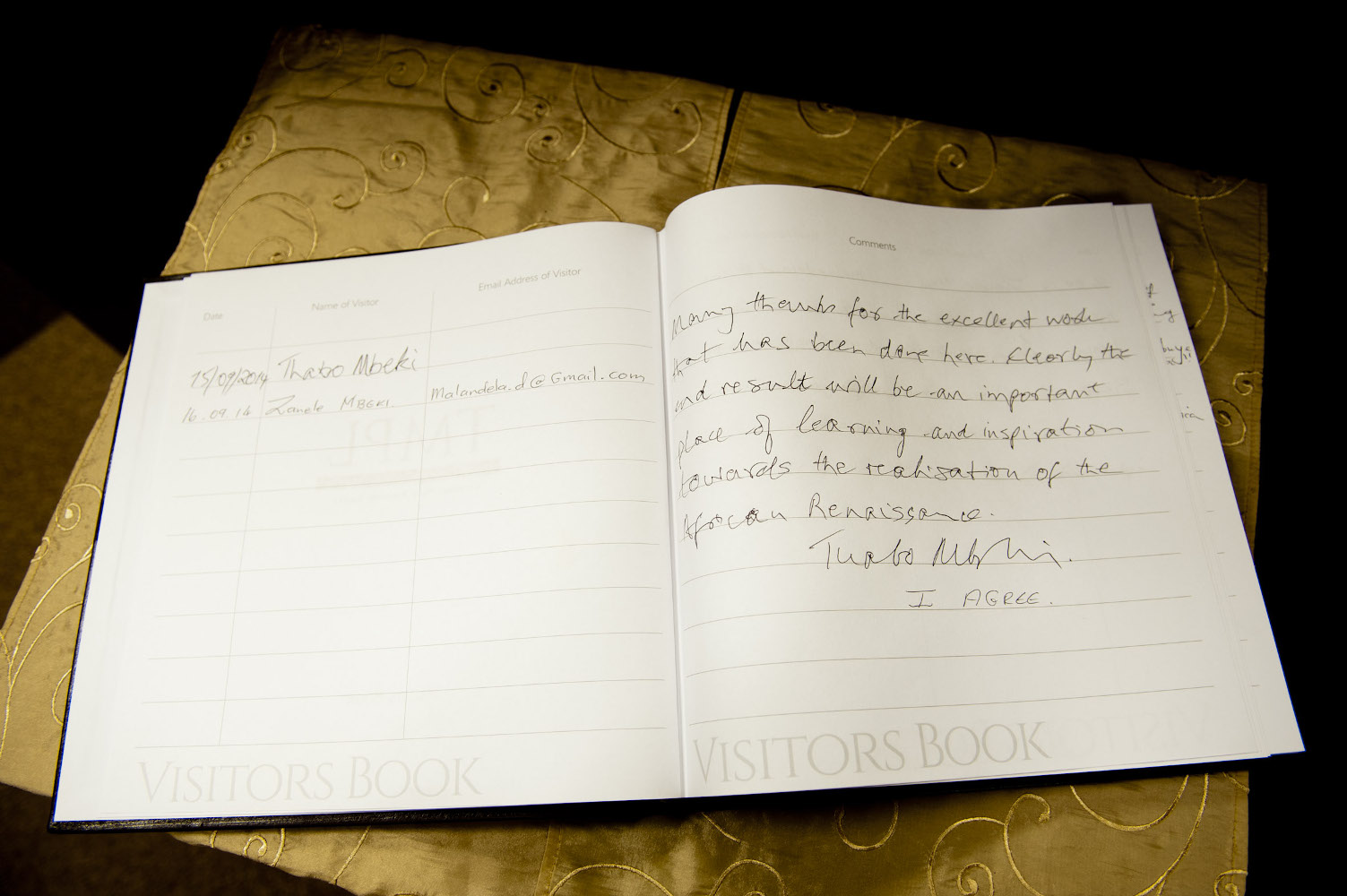

Mbeki himself was not at the event on Tuesday, but Zanele, his wife of 40 years, showed reporters round the room, where cabinets with mementoes from their life together, had been set up.

She told the Mail & Guardian on Tuesday that, along with Barney Pityana, the former vice-chancellor and principal of Unisa, she had travelled to the United States (US) to study presidential libraries this year.

“What I learned about presidential libraries is that they tell their president’s story. Some presidencies are very controversial but what is important is for him [Mbeki] to tell his story. There’s Aids, there’s Zimbabwe, there’s this, there’s that … this is where he can tell his story.

“The Franklin D Roosevelt library talks about the US Depression, the interventions he took during the depression, everything was there, [including his paralysis, caused by polio]. We said ‘We think, here, this is what we must do’,” she said.

“[George W] Bush’s presidency was full of controversy. The war in Iraq was very controversial. He was able to explain why he did what he did in some material in his library. We need our own presidential libraries.”

Communist controversy

She points at the glass cabinet that encapsulates a period of Mbeki’s pre-presidential era. Inside are black and white photographs of her wedding to the former president in 1974. She shakes her head in disapproval, saying what is missing are Mbeki’s archives.

“It is not about artefacts. We want scholars studying the work of African presidents to come here and not have to go to the US for essays they [African presidents] wrote,” she said.

When asked if the work that the former president wrote under the pseudonym JJ Jabulani will be displayed in the library, she said some of Mbeki’s work is in the ANC archives, but discussions are taking place to move some of the original work to the library.

This is one of the controversial matters pertaining to the former president’s economic policies.

When Mbeki wrote under the pseudonym JJ Jabulani, he declared himself a communist. In 1971 Mbeki wrote a moving article in the then banned journal, The African Communist, “Why I joined the Communist Party”. The article described how his upbringing among the rural poor and the urban working class in the Eastern Cape shaped his political outlook on Marxism-Leninism.

“Here, poverty stares you in the face. The filthy, tattered clothes, the tin shacks patched with pieces of cardboard and abandoned rags and sacks,” wrote Mbeki.

During his presidency, Mbeki was criticised by the left in the tripartite alliance for following neoliberal policies centered around privatisation of state-owned companies and tax breaks using the notion of trickle-down economics.

“You must remember that presidential terms are long, this library will provide the platform for Thabo to explain his presidency and for us to share in his ideas,” said Zanele Mbeki.

‘He never asked us to call him doctor’

We stop at the next cabinet. Here is the handwritten draft of the speech Mbeki made at the ANC 75th anniversary of the ANC. Parts of the speech are scratched out, with additions in blue pen.

“He made several changes in the speech. He would make us read it and then make the changes. The speech was to tell [Oliver] Tambo about progress. It was in 1986 and it was about the progress the ANC was making against the apartheid government,” said Zanele Mbeki.

Next to the speech is “one of his eight passports” that describes Mbeki as:

Height: 5’6’’

Hair: Black

Eye Colour: Brown

Nose: Flat

Complexion: Dark

Special peculiarities: None

The passport was issued in the UK.

“On the last page, it said we could go to any country except South Africa. Can you believe it?” she laughs.

There is also a notebook, also written in blue ballpoint, which Mbeki kept at the 1976 Soweto students in Nigeria.

“I took them all [the South African students] from Botswana to Nigeria. The meeting was about the complaints the students had and the way demonstrations were being suppressed by the government,” she said.

The next section of the library has Mbeki’s doctorate of law from the University of Sussex. “And he never asked us to call him doctor,” said a Unisa staff member.

The presidential library will open next year and cover Mbeki’s life from 1955 to the present. The second phase, for which R22-million has been put aside, will take five years to complete.

The Mbeki library is not the first presidential library in Africa. In 2012, Nigerian former president Olusegun Obasanjo opened a presidential library in Abeokuta, Nigeria.

Former Senegalese Leopold Sedan Senghor also built his own library in his home country, which was said to contain all the literature by black thinkers of that time.