If Oscar Pistorius the reckless killer is ever to be rehabilitated in the eyes of a once-adoring public it will begin with the movie adaption of Chase Your Shadow by John Carlin, launched in South Africa last week.

Matt Damon and Clint Eastwood have not yet called to lay claim to the movie rights, Carlin says, so as yet there is no Invictus (the movie about the 1995 Rugby World Cup based on his book Playing the Enemy) in the making. Also, as he grimly jokes, Damon is too old to play the role of Pistorius, and there is the small matter of finding an actor willing to have both legs amputated below the knee to cast the main part.

But Carlin has produced what resembles a movie script before the screenwriters even get their hands on it. And the story is one that has already proved its ability to grip the attention of a significant portion of the world. Signing the contracts to start on the road to a screen adaptation seems a mere formality.

Like Invictus, the movie based on Chase Your Shadow will drive even cynical audiences to tears. This time, though, it will not be the struggle of Nelson Mandela to unite a country that elicits the emotion, or the image of Damon as then Springbok captain Francois Pienaar lofting the jubilation of both black and white.

Instead it will be the image of a toddler Pistorius joyfully bumbling about on his first set of artificial limbs, or a teacher standing awestruck as a “disabled” teenage Pistorius outruns his classmates, or a sister standing sentinel to ensure her broken brother does not attempt suicide. Or, perhaps, it will be the expression on the faces of the parents of Reeva Steenkamp as Pistorius is granted bail even as they have only started to mourn their daughter.

There is certainly enough sadness to go around.

There is also, as things stand, enough prejudice. Some continue to insist that Pistorius is akin to a saint, martyred by the state because of a tragic accident, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding. Others continue to believe him to be a cold-blooded murderer, even though the high court judicially disagrees.

Pistorius as human

Carlin, neither sympathetic to nor respectful of either viewpoint, insists on seeing Pistorius as human, with flaws and redeeming qualities. He draws the reader to the same muddled and uncomfortable understanding. For that Carlin is unrepentant.

“It is something we do all the time, with famous people, with public figures, with politicians, even with political issues. We have a tendency always to try to clarify the unclarifiable, to simplify, to caricaturise,” Carlin says. “And my attempt was to paint the portrait of a complex and, I think, fascinating human being. That may generate feelings of rejection and disgust among people, but I hope above all else it generates some degree of sympathy and a sense of, ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’

“If your starting point is that Pistorius is a monster then you will find this book shockingly sympathetic. But I am absolutely sure, too, that the whole sector of people around the world who believe him to be this heroic, saintlike figure will be equally disappointed.”

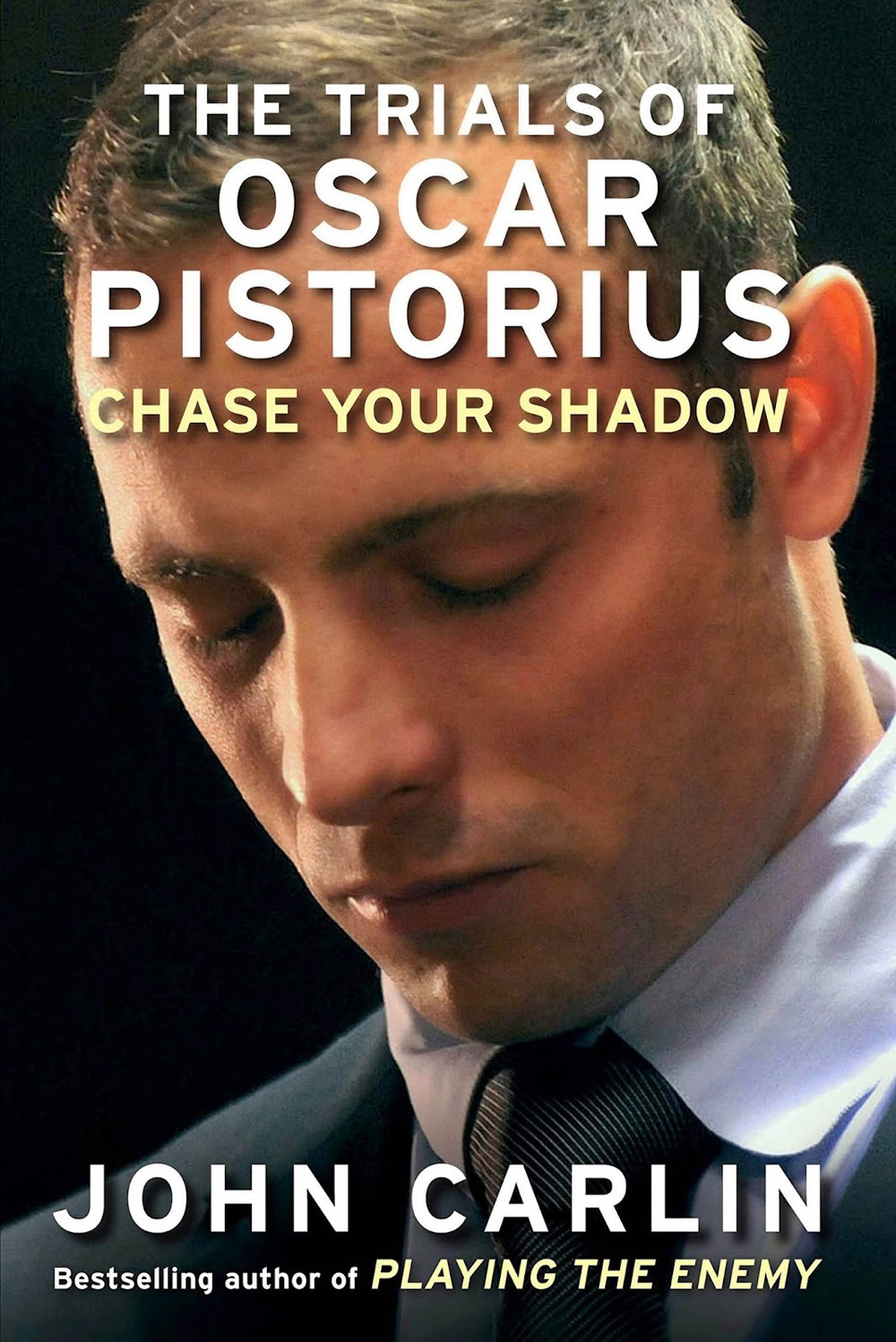

Author John Carlin’s insider-outsider perspective gives him unique insight into both Oscar Pistorius and South Africa.

Carlin has no apparent liking for Pistorius. “He remained trapped in a floundering adolescence,” Carlin writes of Pistorius at one point in the book, “too unfinished to stop the fame and the money from going to his head. He was a teenager in an adult’s body, prone to foolish infatuations with women … irresponsibly susceptible to the allure of guns and fast cars.”

That, it turns out, is not so much a value judgment as an honest assessment arrived at after research spanning three continents.

‘Blinded by bias’

Carlin is equally searing in his appraisal of the South African media “blinded by bias against Pistorius”. And of the “poseurs and parvenus” who make up the Johannesburg glitterati “where leering males hunted for casual sex, where the chatter, the squealing and giggles were all about who was dating who”.

For that matter, Carlin is not particularly kind to Port Elizabeth either, “a plain, listless city”.

It is such clinical candour that makes his case compelling and, though he confesses not to know whether Pistorius wilfully murdered Steenkamp, Carlin has a case to make. Sometimes subtly and sometimes bluntly he paints a picture of a man catapulted to fame and fortune but still terribly insecure and fearful, a public persona of bravado built on a foundation of self-deceit. It is intimate in a way nothing – not the blanket media coverage over many months, not Pistorius’s self-serving autobiography – has ever approached. And with that intimacy, perforce, comes sympathy.

Such sympathy for a convicted killer is all the more unlikely given where Carlin himself began.

“At that time, just after it happened, I did what everyone else did,” Carlin says now. Pistorius, he instinctively felt, was obviously a monster. “And I was outraged when he was let out on bail, as I’m sure a lot of other people were, and I found myself utter phrases like, ‘Oh, rich man’s justice’ and that sort of thing.”

A month and a half later he began writing the book.

Following in footsteps

He travelled to Italy to see the town where Pistorius had trained, to Iceland to meet the family that had joked about adopting him, to the United States to interview the prosthetics engineer who fitted his first “Blade Runner” blades. Through the eyes of these people he glimpsed, for the first time, that the “utterly, ludicrous, insane notion” that Pistorius may have killed Steenkamp by a combination of accident and recklessness could, just maybe, be true.

In much the same way, Carlin began the book project thinking it absurd that South Africa was even debating whether Pistorius could be seen as a symbol, an analogue, of the country. He ended up firmly convinced of just that.

“The country is very much still searching for itself and its identity and what it is going to be,” he says. “It is an adolescent nation … And like adolescents, South Africa sort of goes all over the place in all kinds of different directions still seeking to define itself. That is where I find an analogy in Oscar Pistorius, who, in my amateur psychoanalytic reading of him, is someone who – without realising it – pressed the pause button in terms of emotion at the age of 16 or so and he is all over the place. He is a man of extraordinary extremes, and so is South Africa.”

Carlin comes to explain South Africa by way of Pistorius, sparing the country no more than he does Pistorius – or Port Elizabeth. South Africa is a schizophrenic country, he tells us, where ubuntu and baby rape can sit side by side.

South Africa is a friendly country, no doubt because of a certain “sweetness of nature” of its inhabitants, but maybe also because we realise there are many who are dangerous and unpredictable among us, and we therefore, perhaps “pre-emptively, defuse any danger or evil that might be in their hearts with a smile and courtesy”.

South Africa ‘at its worst’

“After Pistorius killed Reeva Steenkamp, it became tempting to see him as a symbol not of South Africa at its best but at its violent criminal worst,” Carlin writes in the final pages of his book. “That, as Judge [Thokozile] Masipa’s verdict helped indicate, was to oversimplify. Pistorius did remain a symbol of South Africa, but of a South Africa that was complex, ambiguous and could no longer claim to play a heroic role on the world stage. In 2014, Pistorius offered a more faithful mirror of the country than did Mandela.”

Carlin can reach this conclusion as South Africans, perhaps, cannot, thanks to a unique insider-outsider perspective. He was once and is once again a stranger to the country, but one who spent the turbulent period between 1989 and 1995 as a British correspondent here, and wrote two books about Mandela.

His vantage point comes with disadvantages, though, as he tediously insists on framing everything from the Free State province to disability in terms of apartheid – and links what he cannot frame in apartheid terms to Mandela.

Even so, it is hard to argue with Carlin that in the story of Pistorius South Africa can find “a worthwhile mirror” and, if not the final word, then at least some clues “to the nature of this country and its multiple personalities”.