Testing times: The antiretroviral gel

Medication adherence is critical to the study of HIV prevention in women, but researchers are struggling to find treatments that can be adapted to the lives of different women. In the Follow-on African Consortium for Tenofovir Studies (Facts) 001, the latest large-scale study to test the effectiveness of an HIV-prevention gel, researchers found that around 50% of participants were able to use the gel but only one in five used it consistently.

The study concluded that the gel, which contained the antiretroviral (ARV) drug tenofovir, was not able to protect women against HIV infection. Tenofovir is normally used in combination with two other ARVs to treat people with HIV.

The trial results were released last month at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle, Washington.

The Facts finding has renewed discussion around the effectiveness of using ARVs in HIV prevention as a form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In this approach, drugs that are normally used to treat people with a condition are given to high-risk individuals without the condition to protect them from future infection.

PrEP studies that target women at high risk of HIV employ gels, pills, vaginal rings and long-term injections. Gels, including the one used in Facts, belong to a group of compounds known as microbicides. These are substances that can be inserted in the vagina or rectum to help prevent sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Relative success

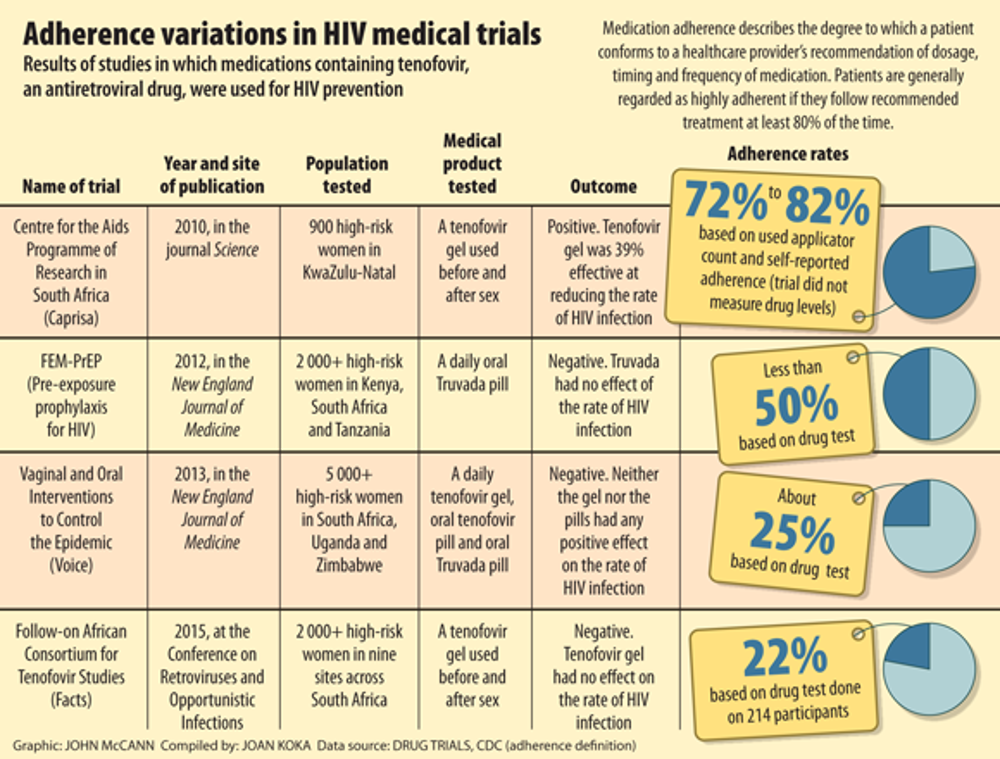

So far, only four clinical studies have found success in using oral PrEP drugs to reduce the rate of HIV infection in various high-risk populations. But only one study has demonstrated relative success with the use of microbicides: the Centre for the Aids Programme of Research in South Africa (Caprisa 004).

In Caprisa 004, researchers found a tenofovir gel reduced the rate of HIV infection by 39% in about 900 women tested in KwaZulu-Natal. But this positive result has not been successfully replicated in any large-scale microbicide study. Reports of inconsistencies in drug adherence in some PrEP studies could in part explain their disappointing outcomes.

Caprisa director Salim Abdool Karim says that getting sick patients to adhere to treatments is a big challenge in clinical research, but getting those without the disease to do so, such as participants in prevention trials, can be an even greater one. Sick people take the medication to feel better, but those participants without symptoms have less incentive to do so because they are well.

Facts researchers measured adherence by counting the number of gel applicators women used and by monitoring tenofovir levels in a small sample of women. Women were instructed to use the gel before and after every sexual encounter.

Inconsistencies

Other large-scale PrEP studies, including FEM-PrEP and the Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic (Voice), used similar methods to measure adherence and also found inconsistencies in drug use.

In FEM-PrEP, researchers tested truvada, an oral drug containing tenofovir and emtricitabine, another ARV, among more than 2 000 women in South Africa, Tanzania and Kenya. Women were instructed to take the pill daily and, though 95% told researchers they adhered to these instructions, less than half had detectable amounts in their blood.

Voice tested a daily vaginal gel and oral tablet in a similar sample of women and found that about 70% of women reported using the gel or taking the pill as prescribed, but only about a quarter had detectable amounts in their body. As with Facts, researchers in FEM-PrEP and Voice found that their treatments had no positive effect on the rate at which women contracted HIV.

The women who were most at risk of infection in the Facts and Voice studies – those who were young and unmarried – were among the least adherent to treatment. These women also had two other distinct features: most lived at home with their family and had little to no income.

Not practical in all lifestyles

“As you paint that picture together, what you are seeing is a young woman who’s got a boyfriend, who’s living in crowded circumstances, so she’s probably staying at the boyfriend’s place, who doesn’t have a lot to dispense for income,” says Facts co-chair Helen Rees. The gel product, its design and application, was probably not practical in such a lifestyle.

“What we’re probably seeing is that people in steady relationships who are cohabiting could use a gel like this. But people whose lives are much more chaotic, who are having sex outside the house, who don’t know how long they’ll be spending with their boyfriend, [are people for whom] we now have to develop technologies that fit into their lifestyle.”

Ariane van der Straten, a behavioural scientist in the Voice study, says that social influences such as negative feedback from friends, family and community members fostered a sense of distrust of the clinical study and a fear of being seen as HIV positive, all influences that could have made women less likely to use the products.

“When you hear your friend, your neighbour, your partner, or other participants in the waiting room bad-mouthing about the product or telling stories about bad research motivations for testing on women, it can be scary. Basically, they got scared and you could see how it’s easy to get scared when you yourself are healthy and you’re testing an investigative product which you’re not even sure works,” she said.

Concealing nonadherence

Fear of failure and of being dropped from the study are common reasons why many women in the Voice and FEM-PrEP study did not report nonadherence.

“One of the main reasons women join the trials is that they receive very good service. They receive health services, they get checked every month for HIV, they are treated with respect,” Van der Straten said.

“[The women] valued that and they didn’t want to lose that. So in some ways they were concerned that if they provided answers that were perhaps not socially desirable like ‘I’m not using the products’ or ‘I’m scared of using the products’ they would be dropped.”

In all three studies, adherence was measured by counting the number of pills or gel applicators used, collecting self-reported information provided by participants, and performing lab tests to detect the amount of ARV drug present in the body.

But drug tests, often regarded as the “true” measure of adherence, have their limitations. One example is that the test for tenofovir provides a “snapshot” of the amount of drug present in the blood but no information about how long the drug has been present or the consistency of use, Van der Straten said.

Better technologies

To improve adherence, researchers need better technologies for measuring it, especially over the long term, she said. Also, drug monitoring should be promoted not as a policing tool but as a way to help women who have difficulties with adherence.

Rees, Karim and Van der Straten agree that technologies must be better tailored to participants’ lifestyles.

Researchers are now altering the design of products to better suit the lifestyles of different populations. For women in the high-risk group, this means introducing products that require less user input, such as long-term injections and monthly vaginal rings. Two studies that explore the effectiveness of vaginal rings – A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use (Aspire) and the Ring Study – are underway in different parts of Africa.

“You can’t keep saying to somebody ‘do something, do something, do something’ when their lifestyle just doesn’t support that approach,” Rees says. “I think one of the issues here is looking for technologies that fit into the lives of different women [such as those that the Ring and Aspire studies are exploring]. The gel fits in some women’s lives but probably a minority. For these very young women, we probably need to get different types of technologies.”

Joan Koka is a master’s student in science journalism at the University of Missouri, Columbia. She is doing an internship at Bhekisisa.