One of Karl Marx’s most repeated quotes is that history repeats itself “the first time as a tragedy, the second time as farce”. Like history, the interpretation of history also gets repeated, first as myth – and then in service of the political agenda of those in power.

That is why Albert Grundlingh, professor in history at Stellenbosch University, really shouldn’t be surprised. But he is.

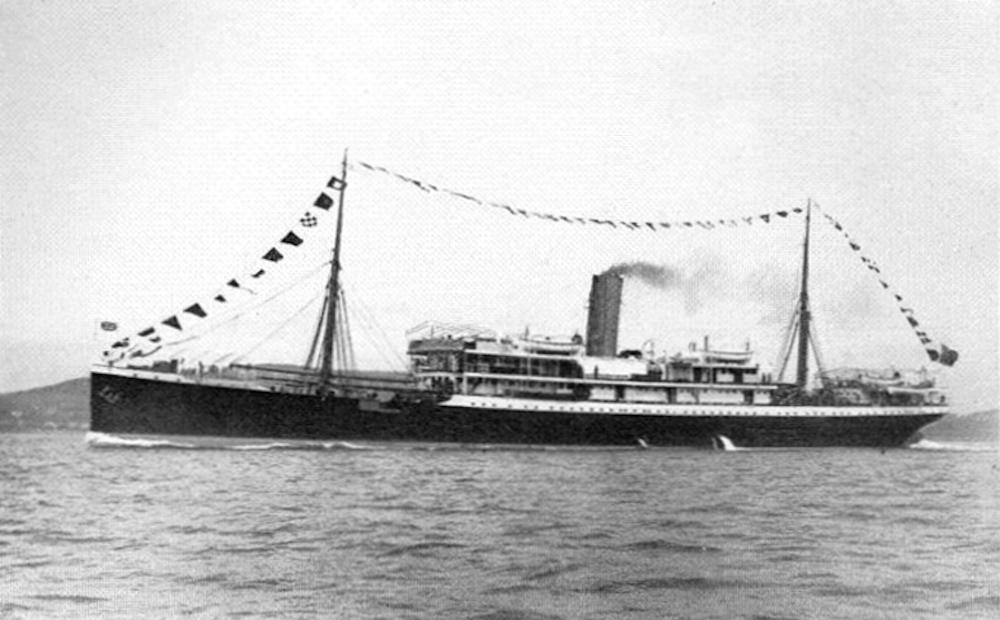

A case in point is the mythologising of the SS Mendi – the ship that sank when it collided with the SS Darro on February 21 1917. A total of 616 out of the 823 men from the Fifth Battalion of the South African Native Labour Contingent lost their lives. The collision occurred only a few hours after the ship had left Plymouth en route to France. The disaster has also served a number of political agendas and Grundlingh brings it under the spotlight in his book, War and Society: Participation and Remembrance – South African black and coloured troops in the First World War, 1914-1918 (African Sun Media).

“Until the 1980s, the sinking of the SS Mendi was commemorated regularly,” said Grundlingh in an interview with the Mail & Guardian. “But then black participation in the war was regarded with suspicion. Those black people who had participated were seen as sellouts. However, in the 1990s the ANC rediscovered the Mendi with a vengeance. And it became a symbol of heroism for the ANC.

“The ANC appropriated the SS Mendi post-apartheid, perhaps because the organisation has a weak military history. Its military wing, Umkhonto weSizwe, was known for armed propaganda rather than armed engagement,” says Grundlingh.

SS Mendi. (National Library of Scotland)

Shortly after the SS Mendi disaster, there were suspicions among some black South Africans that there was more behind the disaster than what has been revealed. But a court of inquiry in England had found that HW Stump, captain of the Darro, was guilty of gross negligence. He had failed to transmit the relevant warning signals and had exceeded the ship’s speed limit for the specific conditions. He also did not do enough to help the men of the SS Mendi who were struggling in the water.

Being aware of these sentiments, General Louis Botha, then prime minister, expressed his and the government’s regrets and sympathies about the disaster in a speech to Parliament. The subsequent motion of sympathy was unanimously passed and led to “the unusual sight of an all-white Parliament rising to pay respect to deceased blacks”, writes Grundlingh.

The government allocated a gratuity of £50 (close to a year’s income for the average black South African at the time) to the next of kin of each man.

Newspapers described the tragedy with phrases such as “they died to set us free” and “those who died by drowning had given their life for the liberty of all peoples of the Empire”.

Yet, “such hopes were forlorn at the time given the powerful forces against equality in South Africa”, says Grundlingh.

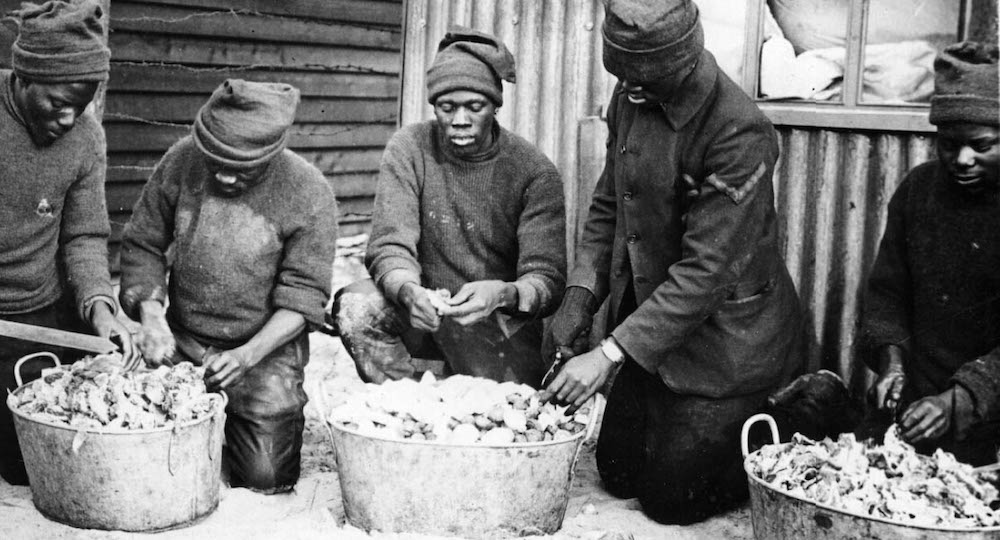

Cheap labour: Even in Europe during World War I, the members of the South African Native Labour Contingent were subjected to segregated living conditions, which left them in basic wooden barracks. (National Library of Scotland)

Nonetheless, the Mendi Memorial Club was founded in 1919 with the support of some white South Africans and foreigners with the aim of keeping alive the memory of the ship and the troops. But this club was run by Samuel M Bennet Ncwana, a former member of the native contingent with a reputation for using funds for his own needs, and the club ran into organisational problems. In its place came an educational fund and an annual memorial day in February.

The contingent’s participation was later acknowledged by a monument in France at Arques-la-Bataille and the names of the Mendi deceased were recorded at the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton. Smaller memorials were also erected in Mthatha, Langa, Soweto and at the University of Cape Town.

There were regular Mendi Day commemorations, but after the National Party came to power in 1948, the government actively discouraged the meetings and fewer people attended these gatherings in the following years.

By the politically volatile 1980s many progressive black leaders felt uncomfortable with the memory of black soldiers participating in a white war. These sentiments were felt on the streets. Black soldiers who had fought in both world wars were seen as sellouts. At the same time, in a seemingly opportunist about-turn from their previous attitude to the fallen black soldiers of the world wars, the white National Party government suddenly recognised their contribution by fixing a bronze plaque depicting the sinking of the Mendi to the South African Delville Wood Memorial in France in 1986.

“This act should be seen against the background of a government desperately casting around for legitimacy in the face of overseas boycotts and sanctions in the 1980s,” Grundlingh says.

The men of the SS Mendi were left in peace by the politicians until 1994. With democracy there was a deluge of pride in this war ship’s heroic soldiers. In 2002 Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, then minister of foreign affairs, in a sitting of the African Union said: “Efforts of Africans to address the problems facing their continent resonate with the aspirations of those brave warriors who perished on the SS Mendi for a better Africa.”

The next year the highest decoration for heroic deeds was named the Order of Mendi for Bravery. In 2007 Zola Skweyiya, then minister of social development, declared: “The courage displayed by these men is now legendary in South African military history.”

‘Never used for political purposes’

Responding to Grundlingh’s statement that the story of the SS Mendi was manipulated by the ANC government to fulfil a particular agenda, Keith Khoza, the party’s communications manager, says that he has not yet read the book.

“However, if somebody wants to make statements about any historical event, they have to be able to deliver proof that what they say is correct,” he says. “The ANC has never used the SS Mendi for political purposes. We commemorate this event as a well-documented historical event.”

Grundlingh emphatically states that mythologising is a common occurrence in all wars and in all countries.

“No matter who we are or from which part of the world we come from, we need heroes, and political parties and groups for social change will not hesitate to create these heroes if it suits their purpose,” he says.

Short leash: White South African soldiers watch a dance by men of the South African Native Labour Contingent, who were not allowed to fight because of South Africa’s segregationist policy. (National Library of Scotland)