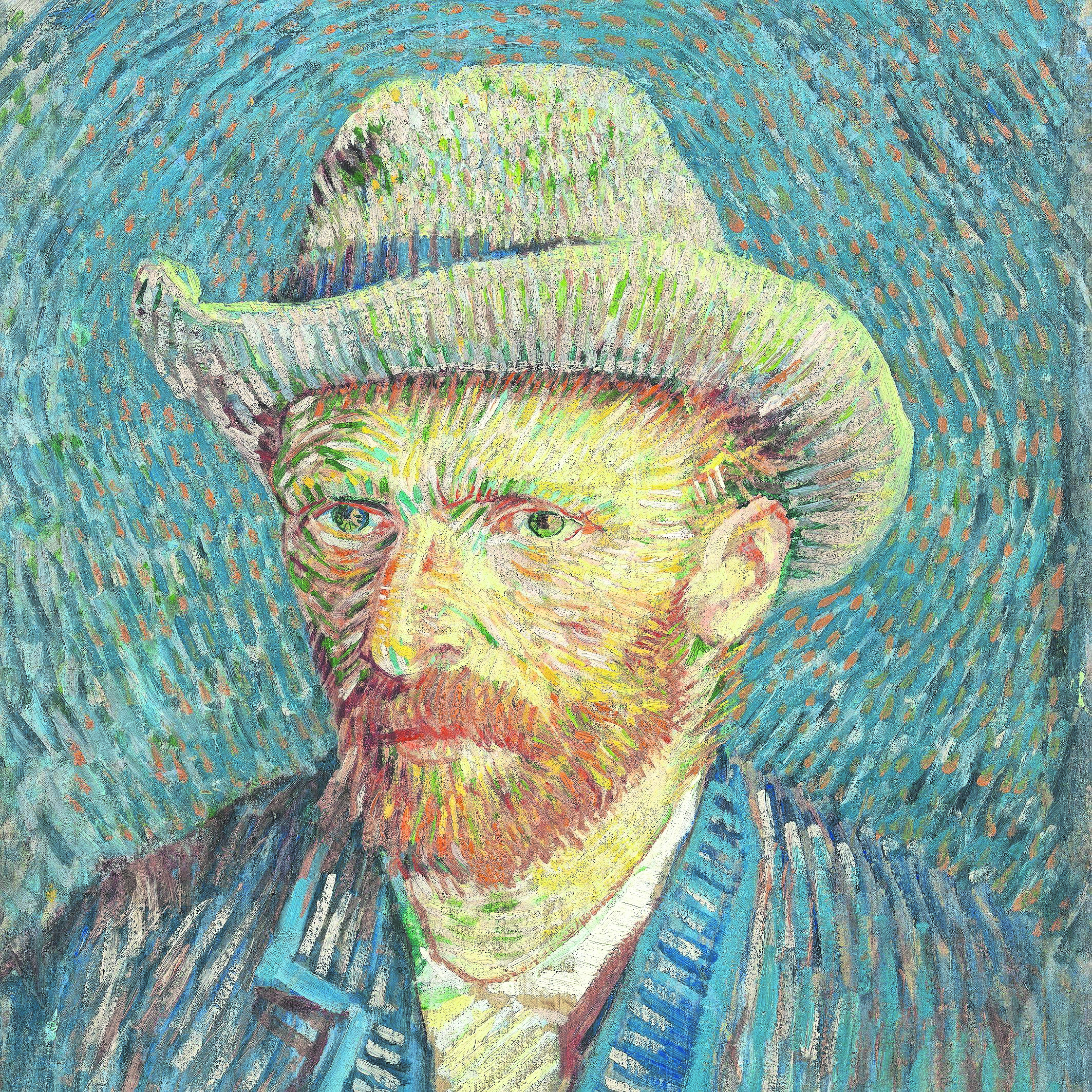

The film "Vincent van Gogh – A New Way of Seeing" is an opportunity to experience Van Gogh's masterpieces such "Self-portrait with Grey Felt Hat"

The life and work of one of the most famously “tortured artists” in history is in the spotlight at Cinema Nouveau this month.

Vincent van Gogh – A New Way of Seeing is a virtual walkabout around the recently re-curated Amsterdam Van Gogh Museum, interspersed with explanations from curators and art historians and dramatic reconstructions of the postimpressionist’s brief but prolific existence (1853-1890) – in which he produced no less than 2?000 paintings, but sold a mere handful.

The film – the latest in the Exhibition on Screen series, an international project that brings significant art exhibitions to cinemas around the world – starts promisingly. It seems set to deliver on its claim made in the media release that it will explore “exclusive new research, revealing incredible recent discoveries”.

We enter the mind of the artist through the image of a dark attic strewn with dusty, unopened boxes. An actor resembling Van Gogh tentatively treads the space.

His familiar, piercing expression freezes and transforms into his famous self-portrait. A voice-over reads from a letter written by Van Gogh to his brother Theo, in which he intricately observes the world around him and seeks his unique place within it, asking: “What most makes me a human being?”

Oddly, the film seems to then turn against the inquisitive mode that this has prompted, dodging compelling questions raised by the same new research it explores.

Were Van Gogh’s hyperproductive tendencies indicative of a pathological illness? Was the severing of Van Gogh’s ear the result of self-harm or an argument with fellow artist Paul Gauguin? Could his mental suffering have had anything to do with an inability to marry his staunch evangelical beliefs with an infatuation with Gauguin? These questions remain unanswered.

“Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat

“Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat

A meaningful human connection

The reluctance to diagnose Van Gogh is understandable – but it produces a searingly “sensible” account of his creative journey that “puts myth and legend to one side”, as if to suggest the possibility of a neat, objective narrative.

By drawing heavily on Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, the film establishes this relationship as the most meaningful human connection experienced by the artist. In doing so, it ignores 10 years of research by art historians Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegan, which observes an intense bond between Van Gogh and Gauguin, who lived together in Southern France in 1888.

They attribute responsibility to Gauguin, a skilled fencer, for the ear mutilation incident, arguing that Van Gogh made up the story of self-harm to protect his friend in a “pact of silence”.

The film glosses over the suggestive ideas that the research throws up, simply painting the artists’ friendship as a “fruitful collaboration” that soured after a disagreement about art. The opportunity to shed new light on possible reasons for Van Gogh’s sharp physiological downturn, culminating in suicide two years later, is squandered.

A cry for help

Sweeping across a room in the Amsterdam gallery that displays 12 self-portraits by Van Gogh, the film acknowledges that he “worked like a madman to push certain thoughts out [of] his mind” but penetrates no further. The argument is that we’ll simply “never know what his illness was”. What we get is a bland abstraction, which fails to address the intriguing theories that present his behaviour as a pathological cry for help.

Shortcomings aside, the opportunity to experience masterpieces such as Sunflowers (1888) and The Starry Night (1889) in high-definition close-up on the big screen is nothing short of spectacular.

So although the film does not interrogate the man behind the picture as provocatively as it might, the visceral closeness it affords to Van Gogh’s work is enough to inspire in audiences a new connection with this revolutionary artist who sacrificed his wellbeing to carve out a “new way of seeing”.