Daniel Friedman and his dog Gangster. The comic thrives on the gaffes and blunders of politicians.

By his own admission, Daniel Friedman, otherwise known as Deep Fried Man, the comic and satirist, was “plump” at high school. He realised it made him an irresistible target for playground bullies and he worked on his material, arming himself with the quick-wittedness and keen eye for natural justice upon which he’s subsequently built a flourishing career.

“My dad [the political commentator and columnist, Steven] introduced me to Monty Python and tried to flog the Goon Show – which mainly failed – when I was younger,” he says wryly, noting that he believes that when it comes to the current social crisis it’s “perfectly acceptable” to use issues such as rape and xenophobia for one’s material, just as long as they expose to ridicule the perpetrators rather than the victims.

“If I had to generalise, you can’t talk about comedy without talking about race in this country; it’s unavoidable,” he says, adding that the British and North Americans, who have been known to tiptoe around such issues, find it amazing that South Africans display such fearlessness in walking across such booby-trapped terrain.

Of the most recent descent into xenophobia and load-shedding, he labels the latter “an inconvenience”, and says of the former “that it’s left a horrible taste in people’s mouths”. His fear is that the embers of xenophobia glow quietly away from prying eyes and simply flare up again when nobody notices, a case of the politicians and councils addressing the symptoms rather than the causes.

Kings and chiefs

The irresponsibility and self-regard of kings and tribal chiefs in all of this is brilliantly addressed in a sketch by Zulu-speaking comedian Skhumba Hlophe, whom Friedman sees as being one of the more cutting-edge comics operating locally today, many of whom are doing their most challenging work away from the cities and in the vernacular, playing to audiences of thousands in the pondoks.

In the sketch we see fictional Chief Geoffrey Mkhondwana, the king of Soshanguve, complaining bitterly that Zulu King Goodwill Zwelethini drives a Merc whereas he’s condemned to busy about in a battered 18-year-old Cressida. “Sometimes things get so bad in this tribe that we have to choose between a new carburettor and groceries,” says Hlophe with an impeccably straight face. “We always chose the carburettor.”

The theme of being bullied is a well-grooved one for local comics, who’ve had to arm themselves with wit to keep the goon squads at bay. Robby Collins, who grew up in the tough Durban suburb of Wentworth, left school before he could matriculate and uses the experience in his routines, some of which will be aired in his new show, That Bushman’s Crazy, due in August.

“I was a horrible learner – that’s why I liked sport and drama because it allowed me to get out of the classroom,” he says. “I went to a gangster government school and I dropped out at 17.

“You can see I’m coloured. I never make it explicit in my routine, but I do use what comes from my life and my upbringing. My brother married a white woman and that’s also changed our life and allowed us to move up in the world. We now drink wine out of the box, not the packet, and my mother has credit for the first time in her life. We travel more, just like white folk, so those are the kinds of things I use in my show.”

In demand

Collins has been much in demand in the past month because of his association and friendship with Trevor Noah, recently lauded with a job as host on probably the United States’s most influential comedy talk show, The Daily Show. “The thing I learned from Trevor is to work hard and be as consistent as possible,” says Collins. “I’ve seen him get a standing ovation and come off stage and not be happy because it wasn’t perfect. From a guy like Loyiso Gola I’ve just learnt that you’ve got to be fearless. If you are going to talk about hectic things on stage you can’t show audiences your fear because if they smell fear on you then they’ll just turn on you and your joke is going to bomb.”

As far as the current moment in South African political life is concerned, Collins is sanguine, pointing out that upheaval is invariably good for the business. “I’m a great fan of Quinton Jones and I remember him once saying that the Vietnam War was great for comedy in the 1970s with guys like Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor coming on the scene. After turmoil it seems like the art really improves, so maybe that kind of thing is going to happen here.”

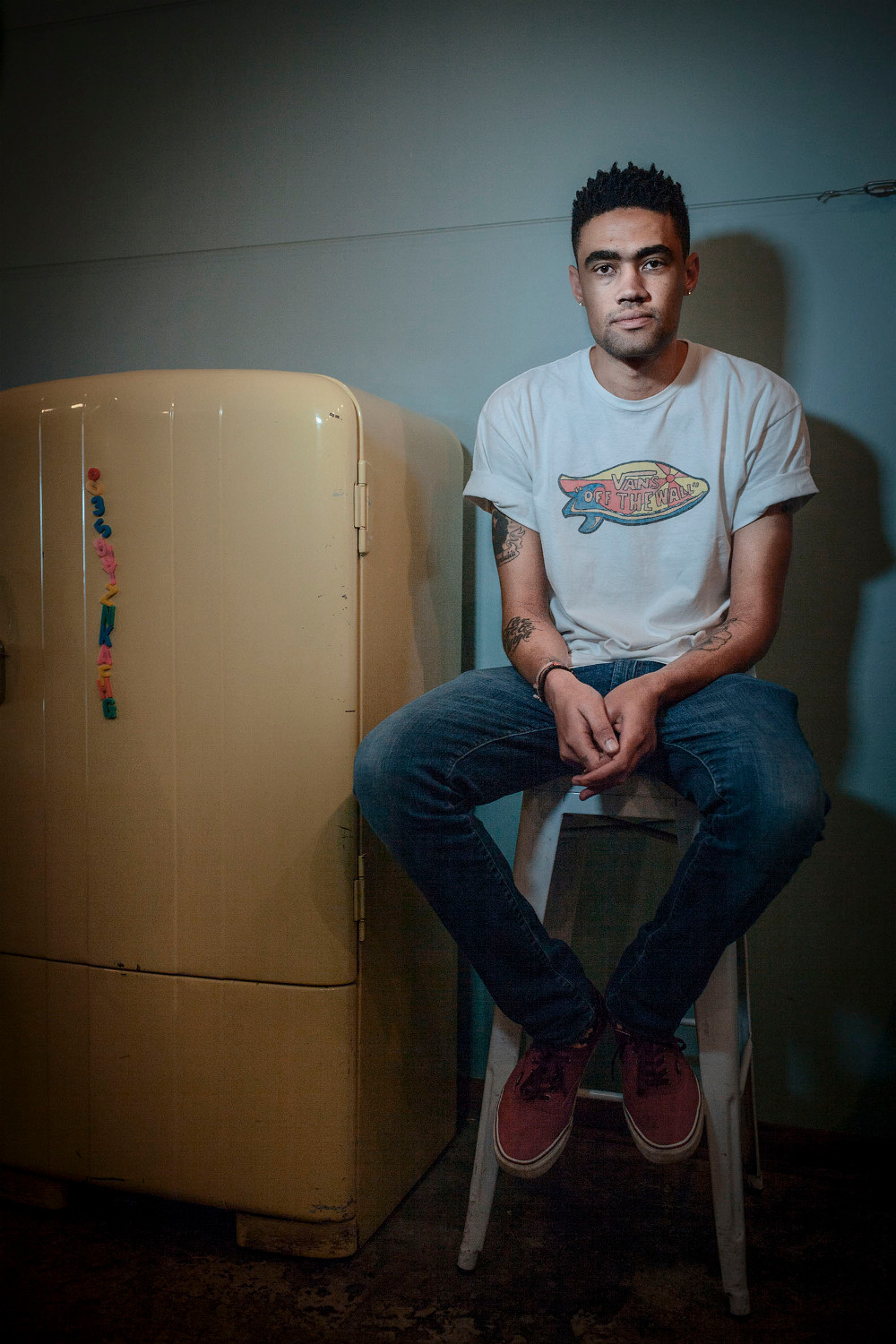

Robby Collins draws heavily on his own experiences to enrich his act. (Gustav Butlex)

All of this presumes, of course, that comedy bubbles along in the wake of big ships marked “society” and “democracy” and “current affairs”. If South African comedy has an obvious failing it is that it has become overly dependent on the idiocy of the politicians, without perhaps looking at life a little bit more tangentially or idiosyncratically – one of the ways in which comics can find their personality or unique voice. Julius Malema or the honourable president only has to open his mouth and the one-liners will surely follow, which rather raises the question of what happens to one’s routine when they stop talking or in the admittedly unlikely event of them beginning to start talking with a little bit more sense or dignity.

Friedman doesn’t explicitly say as much but gives the impression that he understands this better than most. He has piggybacked on popular songs, changing the words to suit his purpose, and once sang a song in which he apologised as a white man for the sins of apartheid.

Broad sensibility

He might not be any funnier than his contemporaries but his sensibility seems broader, although he’s not immune to the all-too-common angst that has him worry about whether he wasn’t once a little funnier. “I have been known to mock white people,” Friedman says. “I wouldn’t call my style gentle but I’m also not one to bludgeon people over the head. Some people have called me brave.

“I guess you could say that my favourite style of comedy is one which makes people uncomfortable but not so uncomfortable so as to not laugh.”

For all comics – whether Friedman, Collins or Hlophe – the issue of where to find one’s material isn’t nearly as immediate or frightening as walking the constant tightrope of performance. Everyone I spoke to said the adrenaline high that comes from being on stage and making people laugh was unsurpassed, perhaps only balanced by the shame and mortification of having an audience figuratively turn their back.

“I’ve often wondered what makes us seek out a career that amounts to nothing more than a constant search for validation,” muses Friedman philosophically, noting that there have been times when a darkened room seemed to be the best place in the world after a show that didn’t go as well as he had hoped.

In all of this it is possible to forget that South African comedy is only in its infancy – certainly in its democratic guise. In this regard Noah has done all South African comics an inestimable service. He has shown what hard work, chutzpah and cultural self-confidence can do, particularly when you have a society as rich in political and verbal absurdity as ours. There will be others following in his wake, of that we can be sure, whether it is Collins and his papsak (wine sack), Hlophe in his battered Cressida or Friedman with his happy caravan of baggage.