When there are rows over transport routes

Once every three months or so, taxi boss Timothy Mazibuko takes over from one of his drivers. Timothy Mazibuko is not his real name because in the volatile taxi industry “you can’t just speak without being given permission”, he explains, “otherwise you get dealt with”.

He gets up at 4am to take the first commuters from Mamelodi, east of Pretoria, to the bustling Van der Walt Street in the Tshwane city centre.

Most of his passengers get out at a busy intersection. Mazibuko, a softly spoken, dapper man who is never without his cloth cap, says he usually just stops in the left lane leaving a column of traffic behind him. Drivers hoot and swear, but there’s no way around it because “his commuters come first”.

Mazibuko likes to keep his hand in: he must know routes, people and problems his drivers encounter on the road. He also sometimes drives his routes to verify that the amount he receives from his drivers is more or less correct.

He adds that the reciprocal honesty and fair treatment of his drivers is essential because “in the taxi industry you can survive today and vanish into thin air tomorrow. How you treat your drivers is very important.”

Mazibuko has three drivers in his employ. He doesn’t want to say how much he makes a year but says that like any other business it can be lucrative when it’s run correctly.

Expelled student

As a young man, Mazibuko enrolled for a science degree at Fort Hare University. He joined the ANC’s underground movement. When he was discovered, he was expelled from the university.

“I had very good knowledge of chemicals. I was once interviewed for a job in government but, on them finding out who I actually was, I was escorted off the premises by the security guards and police,” he recalled. “I am a part of the sacrificed generation, we sacrificed our lives to fight against apartheid.”

The taxi industry was the only place he could make a living.

Two weeks ago taxi violence made news again when taxi operators, drivers and leaders protested against the introduction of a new player, state-owned intercity operator Autopax, in Mamelodi. The problem began with the withdrawal of the Putco bus services from routes it had operated for more than 19 years. Gauteng’s transport department, under executive council member Ismail Vadi, granted Autopax an interim tender of three months to operate in the area.

Autopax buses started running in Mamelodi on July 1; taxi operators protested by stoning the new service. The protests carried on to the second day and metro police, with the South African Police Service, escorted the buses out of the township.

The violence escalated. On Friday, July 3, a Putco bus driving down Solomon Mahlangu Street was stoned and shot at, leaving four people injured and one admitted to hospital.

‘Taxi violence’

The incident was termed “taxi violence” by the Gauteng provincial government and Premier David Makhura said: “We are not going to allow anyone to hold us to ransom. If the police must be reinforced with the South African National Defence Force, it will be done.”

At issue are lucrative routes out of Mamelodi and the contracts the Gauteng government awarded Autopax.

Vadi says the tendering process was closed. There was no requirement for his department to go on an open tender process because the contract was a short-term arrangement between two government agencies.

Vernon Billet, secretary general of the South African National Taxi Council (Santaco), says the organisation never saw, in any government gazette, adverts for operational licences for Autopax buses. Affected operators were not called to meet to tender for the contract, he says.

The focus then quickly shifted to taxi violence and the possible re-implementation of Operation Fiela into Mamelodi. Santaco, through the organisation’s president, Philip Taaibosch, admits that their members threw stones at the new buses in protest. It denies involvement in the shooting because “our members’ issues are with Autopax and not a Putco bus that was driving from Mpumalanga and only passing through Solomon Mahlangu Road”.

Intimidation

Billet accused Makhura and Vadi of intimidation and trying to pit the media and the Mamelodi community against the taxi industry, holistically dismissed as violent. By doing so Makhura and Vadi would not deal with the real issues on the table: the Autopax contract, the issues of subsidy and the “destructive competition” driven by government.

Billet says the taxi industry was started without subsidies and continues to exist without subsidies. “One passenger is subsidised in the bus coming from Mamelodi. The next passenger in a taxi also coming from Mamelodi is not subsidised.”

With the contract being awarded to Autopax, it took away an opportunity that ensured all operators and stakeholders were satisfied, according to Billet.

A heavy police presence at the Putco depot in Mamelodi. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Taxi boss Mazibuko says contract corruption and route invasions were two major causes of taxi violence. There were rogue elements in the taxi industry who preferred to use violence and intimidation instead of reason.

He says that when Putco announced it would pull out of its services in February, the local taxi associations’ leaders told their operators they had entered into an agreement to take over the routes with the Tshwane municipality.

“Now taxi operators are profit-minded people,” says Mazibuko. “When they are told of an opportunity such as this, they prepare. Some bought mini buses. A lot of money was spent in preparation for this.

“But I thought, ‘Ke sailo bona mothlolo mo. Bare ho setse beke fela?’ [We are going to see a miracle. You mean to tell me we’ll take over in just a week?],” he laughs.

“Don’t misunderstand me. The taxi industry is in its embryonic stage. Our guys need to be trained. We don’t have ticketing, we don’t have schedules, we haven’t proved ourselves trustworthy to the government and they are mandated to provide this service. What happens to the commuter if we fail?”

Transport subsidies

Mazibuko says another point of contention in the taxi industry is the subsidising of bus and train services by the government, a practice started during apartheid.

Vadi says Gauteng has 63 000 taxis on its system, of which 45 000 have been recorded. “How do you now contract with 45 000 people with route 1, 2, 3, 4 etcetera … and monitor that? And say we subsidise it and monitor it? I will need a whole bureaucracy to monitor that. But if they [the taxi operators] form companies, either in the region or municipality then we will look at it.”

Vadi says if that was done the province could consider possibilities of subsidising them.

Free Market Foundation’s Eustace Davie, having done extensive research on the taxi industry, says the lack of formalisation in the industry is an excuse used by the government not to enter into good faith contracts with the industry.

He recommends that commuters be subsidised by means of tickets. “These tickets would be presented when using public transport and the commuter would only pay the difference. It would be up to the operator to keep track of all tickets and if they chose not to use them, the commuter would be well within their rights to choose a different operator.”

Mazibuko says the unfair competition often led to violent protests. However, even with all these difficulties, taxi violence needs to stop. He says minibus taxis, buses and trains are all part of the public transport system.

“All the government needs to do is improve our conditions so when we compete, we are on the same floor.”

Minibuses keep SA moving

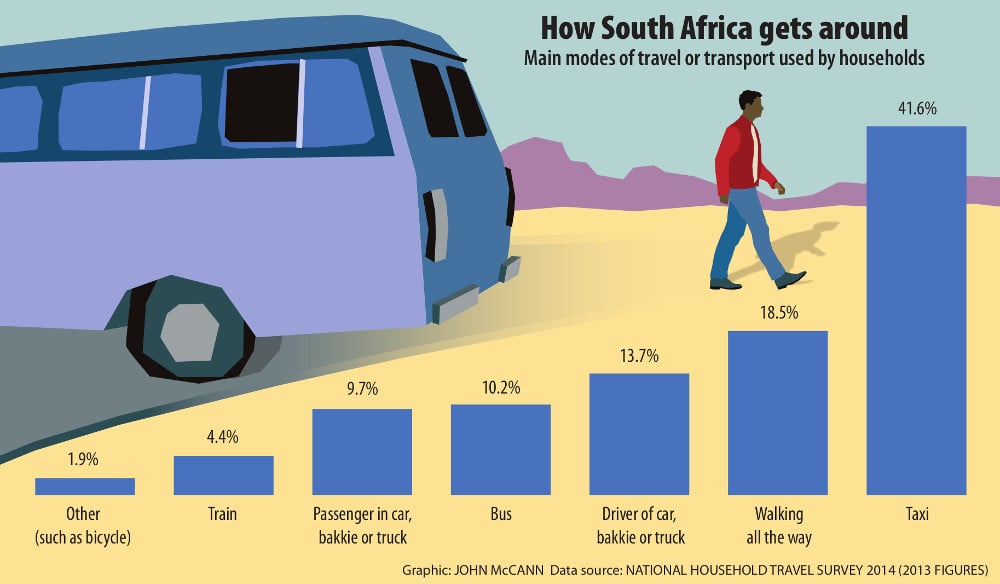

About 15-million South Africans take minibus taxis to work every day. Between 2003 and 2013 the percentage of households who use taxis increased from 59% to 69%, according to Statistics South Africa.

The taxi industry made about R90-billion in revenue and spent roughly R15-billion a year on petrol, said South African National Taxi Council (Santaco) president Philip Taaibosch.

The Free Market Foundation’s Eustace Davie said: “About 180 000 people are employed in the industry, including drivers, taxi marshals and administrators, but this is not easily verifiable because of the informal and dynamic nature of the industry.”