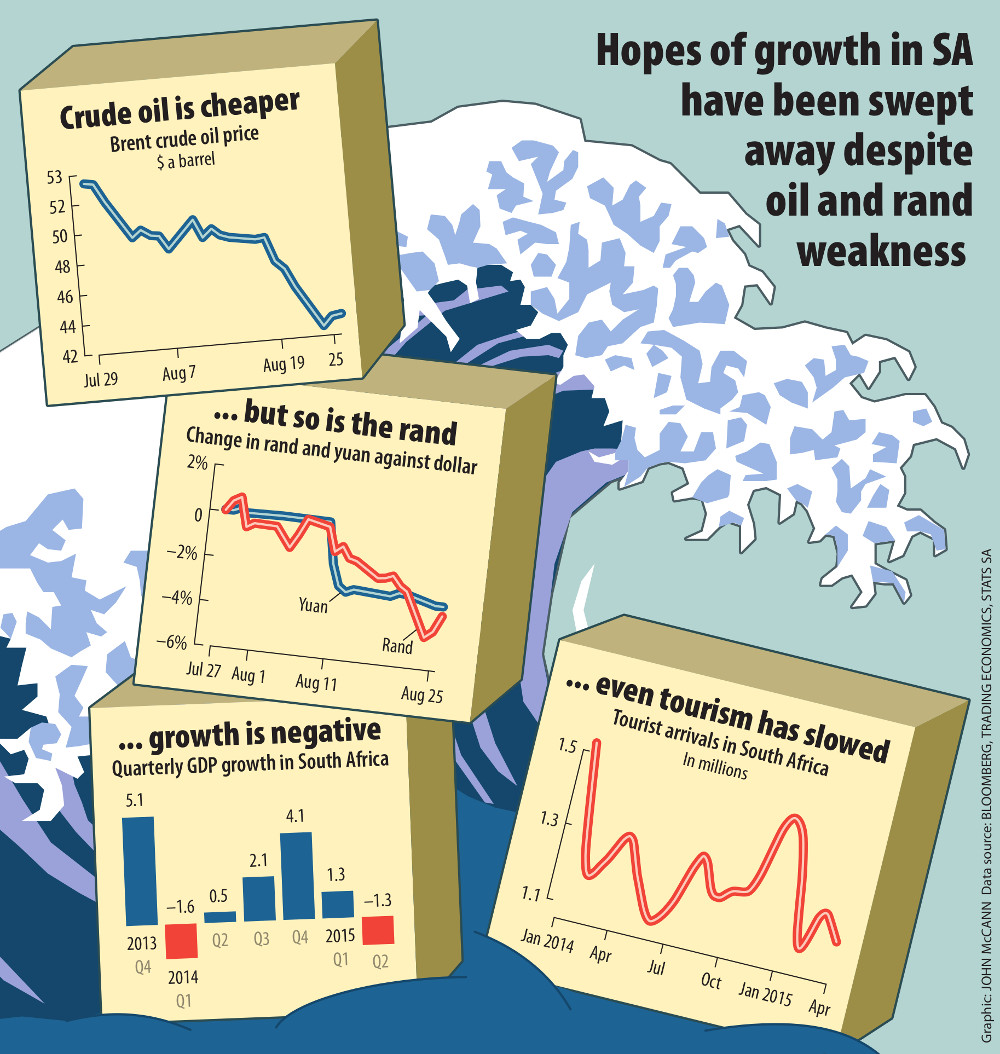

Amid poor economic data, most notably poor gross domestic product (GDP) numbers and a weakening currency, the low oil price is a reminder that things could be worse.

While commodity prices continue to fall as China falters, South African motorists rejoice because a lower oil price likely means a drop in the petrol by as much as 70c next week. Of course, the price drop would have been higher had the weak rand not offset some fuel-price benefits. The rand traded from between 12.95 to 13.67 this week – weaker than 11.27 in January, or 10.62 last September.

A weaker currency is not all bad news. It may make imports costlier, but would see South African exports become cheaper globally – a boon for export-oriented sectors.

As energy constraints dragged economic growth in the second quarter, it may prevent export-orientated industry from taking advantage of the weak currency through expansion.

Said Azar Jammine, chief economist at Econometrix: “Possible benefits for the real economy could transpire for this kind of situation, but we don’t want to overstate that: there is a lot of industrial action in mining and manufacturing, and issues with tourism, preventing us from capitalising on the low rand as we should.”

Tourism numbers released by Statistics SA this month show a slow growth of 0.1% between 2013 and 2014. New, stricter visa regulations introduced recently by home affairs, critics say, will have a negative effect on tourism. India, whose currency trajectory against the United States dollar is similar to that of the rand, last week reported a 1 000% growth in tourism since it introduced a fuss-free e-visa nine months ago.

Economists believe farming benefits from a lower fuel price, which constitutes about 11% total variable costs of grain production.

According to Grain SA economist Wandile Sihlobo, the lower price is welcome – but would have been a larger drop had the currency not weakened as it had. The weaker rand is negative for agriculture in other ways, especially at this time of the year when farmers start preparing their soil for the next season, he said.

“South Africa imports roughly 70% of the domestic fertiliser consumption and 98% of agrochemicals, so a weaker rand worsens the inflationary effects in these products,” he said. “Fertiliser constitutes roughly 30% to 35% of total variable costs of grain production, so an increase in prices will lead to increased input costs and add pressure to farmers.”

Mining incurs costs on domestic currency but it earns in dollars and benefits from a weaker currency.

René Hochreiter, an analyst at Noah Capital Markets, said not all platinum group metals miners would benefit from the current economics. By calculating the last reported costs of a company, the spot rand price and platinum group metal (PGM) prices, Hochreiter determines how many out of 15 PGM companies are working at a loss at any given time.

“At the beginning of the year, when PGM prices were higher and the rand was stronger, we had four mines working at a loss. If we go back to 12.50 to the dollar, and a lower PGM price, five mines were working at a loss.”

For every mine’s margin to be positive, the rand must go to R15, he said. The inflationary pressures coming with that kind of exchange rate would affect wage demands.

Nedbank chief economist Dennis Dykes said the inflationary effect of the rand at the moment was not coming through as it normally would. This is clearest in durable goods inflation, which grew 2.4% year on year. This, Dykes said, is an indication producers cannot push price increases through to consumers. “There is no demand-led inflation. It’s been a very bizarre time.”

Jammine was reluctant to adjust his inflation forecast. “Oil prices have fallen dramatically, but that is part and parcel of the same story of the rand falling, which is weak Chinese demand, which resulted in weak commodity prices more generally.”

It’s likely the weak currency’s downward trend will outperform the benefits from the oil price, he said, noting that the weighting of petrol in the consumer price index basket is 5.68%, whereas imports played a more substantial role in the economy and, as such, rising import costs will have more of an effect.

According to Dykes, current circumstances may translate into a narrower current account deficit, but for the wrong reasons. “The deficit could come in smaller than expected, but for reasons related to less imports and no export response. As far as fiscal deficit is concerned, the circumstances only make things worse. If GDP growth is weak, it will have an impact on business and then income tax won’t be as high as expected and sales tax will also be affected.”

GDP figures are not just at risk of simply being weak; the latest numbers have ignited concerns over a recession when numbers for the second quarter of 2015 showed a decline in growth by -1.3%. Year on year the economy grew by 1.2%, which was well below market expectations.

“There is a real risk South Africa will experience outright economic recession over the coming quarters,” said Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings, adding it was crucial that economic policy leaders find ways to encourage business investment. He said this could be achieved with firmer implementation of the national development plan, targeted infrastructure development and labour market stability.

“Government should increasingly adopt a more practical approach to resolving key infrastructural bottlenecks,” he said.