The statue of Cecil John Rhodes on the campus of the university of Cape Town

It took one single act of self-incineration by Tunisian hawker Mohammed Bouazizi to spark off the Arab Spring.

Likewise, it took faeces splattered on a statue of Cecil John Rhodes from a township bucket in March this year to set off a wide-reaching students’ movement.

There is an old saying that one man’s shit is another man’s treasure.

When Chumani Maxwele flung his container of human excrement it was not the start of the protest, nor was it the end. But, as the action attracted media attention, it marked perhaps the first significant public acknow-ledgement of what would become known as the #RhodesMustFall movement – a literal tipping point that, in turn, would subsequently birth a national collective student protest under the expanded banner of #FeesMustFall.

In October, university students marched on Parliament and the ANC’s headquarters, Luthuli House. Then they marched on the Union Buildings. The Twitter hashtag of #FeesMustFall topped local trend lists and allowed the nation to connect – as bystanders, supporters, objectors, providers of food or water or airtime or bail money. The suffix “-mustfall” was promptly appropriated, both with and without irony. Now everything must fall: colonialism, heteronormative capitalist patriarchy, Zuma, rain.

Are the students standing at the precipice, catching the first glimpses of a coming revolution?

Are we as South Africans, almost 22 years after the collapse of legislated apartheid, fed up with episodic injustices (Andries Tatane’s death and the Marikana massacre were a mere 16 months apart) that we silently or actively cheer anything that looks like the proverbial storming of the Bastille?

The answer is yes, if we believe the hype. This year (the media tells us) was the year of the student, and the student is our “person of the year”.

But the shit that Maxwele threw was, literally, the same old shit. And he knew it. The evening before the Rhodes statue protest at the University of Cape Town, Maxwele had visited Khayelitsha where he stole a portable flush toilet together with its contents. It was the very same model of toilet that had been at the centre of the much-derided “poo protests” back in mid-2013, when residents of Cape Town had, similarly, flung faeces at the symbols of an establishment that was insisting they should be happy to shit in a bucket that nominally flushed. There was no commensurate outpouring of support, no poo zeitgeist. For this shit to have any sort of value, it needed a different target (audience).

The convenience of a hashtag typically elides these and other formative stories from the popular narrative, but not necessarily from the students’ own discourse. Social media may have broadcast the story of the Year of the Student, but it was always only a vector, not an agent.

“In the political and intellectual history of Western society, it is Marxism that has claimed the concept [of revolution],” says University of the Witwatersrand #FeesMustFall member Lwazi Lushaba. “It assumes a palaeology. We assume that it has to be waged by a certain class. If you look at how revolutions have been defined, the capability rests on modernity and urbanity. You never hear of rural people waging a revolution. Once you frame it as a revolution, people think a revolution is supposed to achieve one, two and three. Others will say it was not a revolution because it did not achieve certain things, like the Arab Spring. People say it was a failed revolution but those societies have changed.”

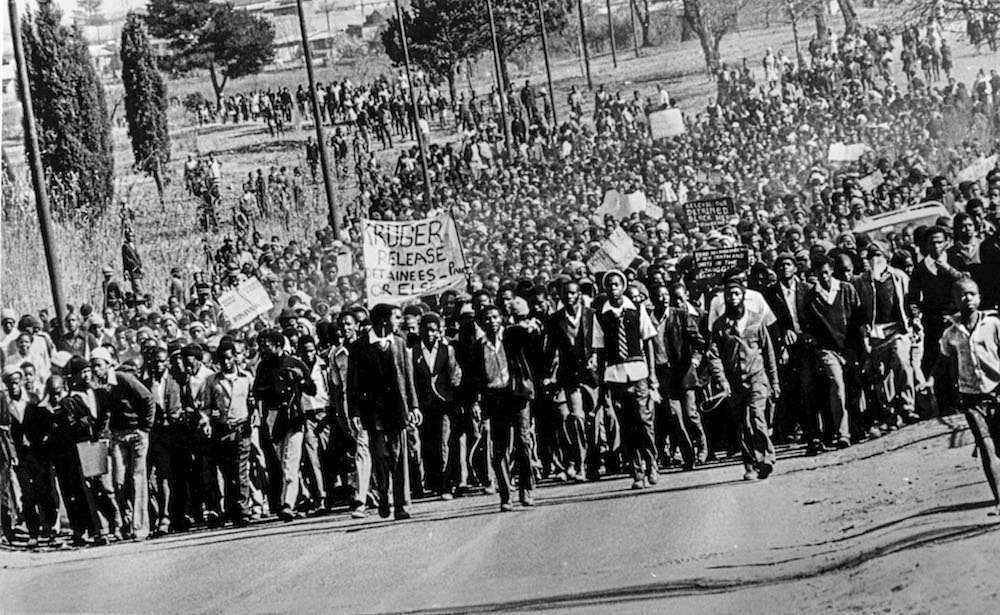

Uprising: Students march in Soweto during the 1976 protests. (Robben Island/Mayibuye archives)

It is easy, too, to understand the desire to compare the class of 2015 with the student uprisings of 1976. University of Johannesburg-based activist, researcher and PhD candidate Trevor Ngwane says that students function as a barometer of society, able to transmit the rumblings of the lower middle classes as well as the working classes. This is why as a society, he says, we can expect “big struggles” over the next few years. “After 1976, there were the 1984, 1985 and 1986 uprisings that nailed apartheid.”

But even this exposes the folly of centering the narrative around “the student”. The deepening resistance to apartheid in the 1980s was fought on many fronts in the townships – it required the efforts not just of the youth but also of women, of workers’ unions, of rent boycotters …

“Apartheid was not unravelled in elite spaces or places of privilege,” says Professor Premesh Lalu, director of the Centre for Humanities Research at the University of the Western Cape. “It was unravelled in places where people were creative and thoughtful.” Places, he says, that are now “marked by atrocity and underdevelopment. But those are the places that proved to be most thoughtful at the height of the struggle against apartheid.”

One could argue that, as in other uprisings, it was the actions of the students that functioned as the all-important spark. Such was the case with the 8888 protests in Myanmar, where what was initially a distinct student-led protest quickly swelled into a mass of national protests, joined by farmers, workers, and even monks. On August 8 1988 the ruling junta’s security forces opened fire on some of the crowds. Thousands were killed; many (as in South Africa in 1961, and in 1976, and …) had been shot in the back while trying to flee.

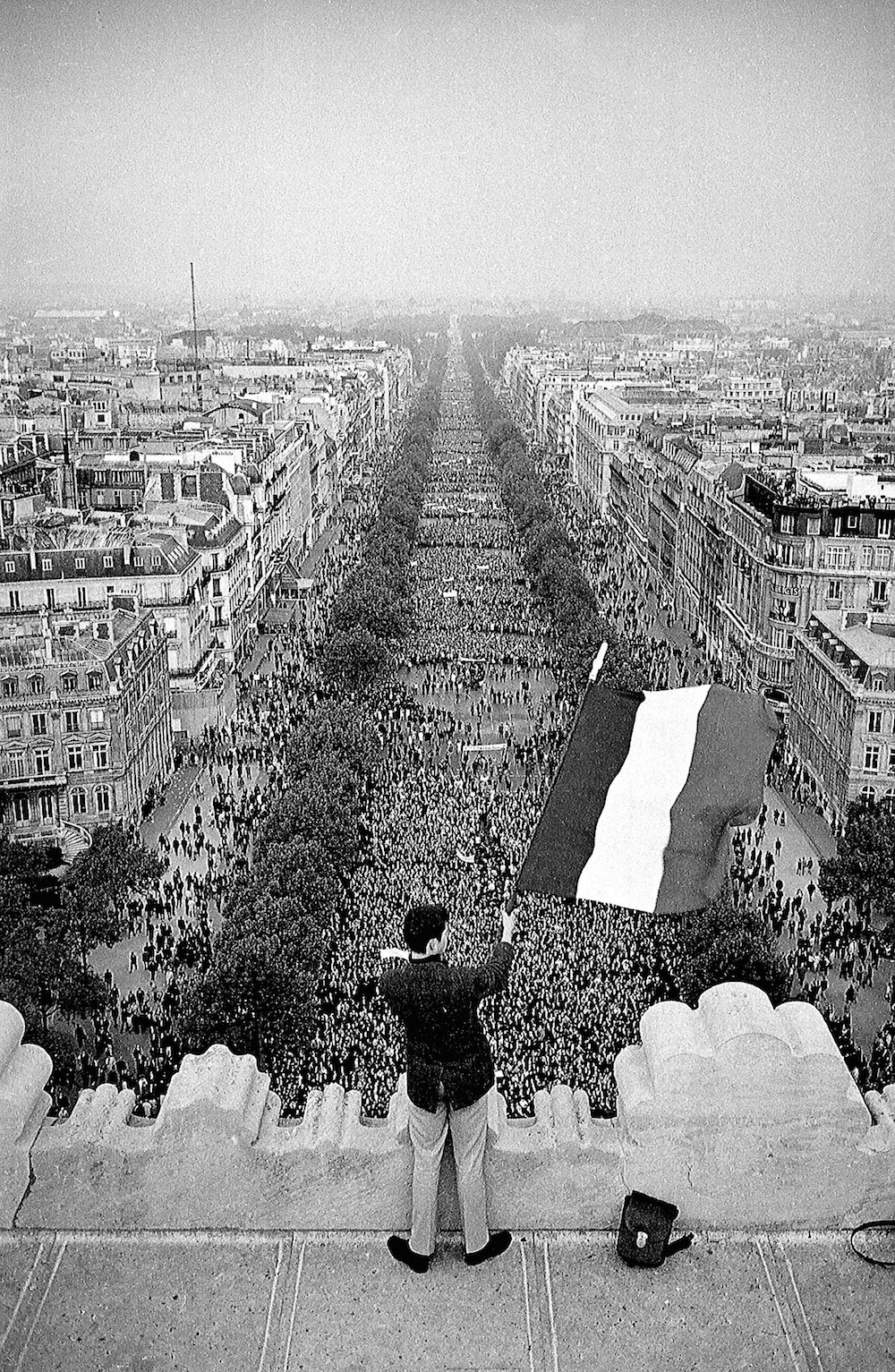

Students gather in Paris during the ‘other French revolution’ in May 1968. (Robben Island/Mayibuye archives)

But then there is the (other) French revolution, of May 1968 – a slightly romanticised student campaign that captured the imagination but ultimately failed to gain sufficient traction with a parallel workers’ revolt (the New York Times once described it as the “revolution that never was”).

Although President Charles de Gaulle was forced to dissolve the National Assembly and announce a new election, the all-too-brief moment when it seemed France might indeed be on the brink of a real leftist revolution quickly passed, and De Gaulle and his supporters were quickly voted back into power (with an absolute majority too!). Plus ça change, as they say.

Thabiso Bhengu, a researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand and popularly known on Twitter as @fistvoices, says the “decolonisation project” is a lead-up to the revolution. “Ours is a commitment towards decolonising the world we live in. Any political agenda that seeks to oppose this will be met with tremendous revolutionary violence,” he tells the Mail & Guardian in an email.

Lalu, however, offers another perspective. “The current debate for me appears somewhat reductive,” he says. “What we are doing is treating colonialism in quite the same way liberalism tries to see its relationship to apartheid. It is a reductive racial reading of the problem of colonialism.”

Lalu suggests we start to think, instead, about “the concept of the post-apartheid. The problem is that we have thought about decolonisation as an extension of the development of a narrative of ‘under-development’.

The question of post-apartheid requires a different sensibility, getting beyond a narrative structured around need and what the state can deliver and so on. It’s about how we make possible worlds that are nonexistent. No post-apartheid is going to be delivered,” Lalu says. “There is only one that is going to be thought and made.”

A better way to understand the impact of the student protests, then, would be by its duration.

“Histories are constituted by two things,” Lalu says, “by events, or by duration.” And, “with the rise of new technology, the question of time has become constricted. We think about events in very immediate ways. But actually histories, even revolutionary histories, are profoundly about duration,” he says, mentioning the influence of the work of West African philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne.

“That doesn’t mean we’re not going to see changes that are dramatic,” he adds, citing Egypt’s Tahrir Square uprising as an example, but says that we still need to take a longer view on history. “The idea that revolutions happen as eruptions is a particular conception of history that I don’t necessarily find useful. Duration is not time stretched out, or time on a continuum. Duration is how you come to live in the present.”

Lalu says that, in order to discuss such questions – and to find new ways not just of talking about them, but also of thinking about and describing them – we need to continue to create new spaces and histories where such thoughts can flourish.

And “they are happening. I’m completely amazed at how much is happening,” he says, with many (perhaps even most) such innovations taking place well off campuses, away from the trolls and adjudicators of social media.

One example of this is the annual puppet parade in the Karoo town of Barrydale, which is presented by Net vir Pret (Just for Fun) and the Handspring Trust of the Handspring Ukwanda Puppet Collective. This year the theme was Die Name Wat Ons Gee (The Names We Give),and explored themes of slavery and indentured labour in the farming district.

“Young people in rural areas were thinking about where their names came from, and how slavery was part of their inheritance,” says Lalu. “It is profoundly important. We need more history, not less.

But more history of a different kind. And,” he finishes (paraphrasing French historian Jules Michelet), “we need a history that teaches us how we live, not only how we die.” – Additional reporting by Kwanele Sosibo

We’re liberated, but we’re not free

“Thus, in this precise sense, emancipation cannot be the guiding light for liberation/decoloniality but the other way round: liberation/decoloniality includes and remaps the ‘rational concept of emancipation’.” – Walter D Mignolo

The arc of revolutionary justice bends towards decolonisation. The moment that Nelson Mandela was sworn in as South Africa’s first democratically elected president was an incomplete one, its missing elements to be revisited at a later time.

That time has arrived, not just in the form of the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall student protests but in our debates as we tussle with the meaning of being formerly disadvantaged beings in an emancipated state.

For most South Africans, 1994 was a moment of freedom. April 27 is celebrated as Freedom Day.

However, decolonisation makes us consider it a moment of emancipation, or of narrow political reform and class ascendancy, rather than one of freedom, a moment of complete change.

Black people gained buy-in to a system that remained colonial without changing it into something else. Professor Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni argues in Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonisation that emancipation is incomplete, as the freed slaves of the United States found when emancipation continued to trap them on the very lowest rungs of a racial-hierarchy society, necessitating a civil rights movement.

“The post-1994 South African situation speaks volumes about how the liberation movement was disciplined into an emancipatory force that finally celebrated the achievement of liberal democracy instead of decolonisation and freedom.

“This means the day was won by liberals rather than nationalists,” Ndlovu-Gatsheni wrote.

Much of the criticism aimed at the student decolonisation movements misses that point. This is not about redecorating a few campuses but uprooting an entire system and replacing it with something else. There is no vocabulary for it other than “trauma” within a liberal world view. There can be no reaction other than denunciation and resistance.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni further separates decolonisation from liberalism thus: “In Africa, the genealogy of liberation discourse is traceable to slave revolts and primary resistance, and in the diaspora to the 1781 Tupac Amaru uprising in Peru and the 1804 Haitian Revolution.

“The resisters who participated in these struggles did not fight for internal reform within Western modernity and its logic of imperialism and colonialism … The clarion call was for independence, not reform of the system as emancipatory demands tended to do. Liberation is the expression of aspirations of the oppressed non-Western people who desired to de-link with the oppressive colonial empires.”

This distinction is why critics, who are embedded within the 1994 moment, fail to appreciate the ambitious vision of decolonisation, not to mention the distinction between emancipation and freedom.

Ferial Haffajee displays this amply in her book What If There Were No Whites in South Africa? when she dismisses decolonisation as an “obsession with whiteness”.

She writes: “When I preach my gospel of change, of black accomplishment and of the good and healthy fruits of freedom, it is as if I am the anti-Christ. It is as if I have journeyed to a place where nothing has changed, where an oppressive minority controls thought and destiny.”

That is, in fact, precisely the place where she finds herself. The liberation movements understood, in theory at least, that 1994 was not the end of the natural end-point of the revolution.

The South African Communist Party’s Paths to Power paper, adopted in 1989, argued that it was necessary to place a moratorium on the attainment of socialism in order to preserve the unity of the liberation movement.

Certain elements of the ANC used the fourth national policy conference in 2012 to pave the way for a realignment of powers that would give the president broader powers over the economy.

That paper was watered down by opposition within the ANC until it gave way to the National Development Plan. The debates about social and economic transformation have receded from their high points within the tripartite alliance. The ANC must also grapple with the irony that, as a party of government, further transformation requires it to break and remake a system it worked very hard to join.

The vast patronage network built around the reallocation of state resources and black economic empowerment deals for a connected few further reinforces its position as a protector of the system.

Several thinkers, including Nigerian political theorist Peter Ekeh, force us to consider that the current state of the ruling party was inevitable. The African bourgeoisie class, the protagonist in the clash against colonisation, depended on it for legitimacy once it came into power. “[The African bourgeoisie class] accepts the principles implicit in colonialism but rejects the foreign personnel that rule Africa,” Ekeh wrote.

For all the talk of postponed revolutions and second transitions, the heart of the decolonisation movement increasingly lies outside of the tripartite alliance – notwithstanding the involvement of certain ANC Youth League figures in the #FeesMustFall protests.

The decolonisation movement is enjoined with the responsibility of imagining a new system. It is here that its commitment to radical change will be tested.

Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek famously dismisses “the 20th-century communist project” as a total failure and Karl Marx’s notion of a communist society as “itself the inherent capitalist fantasy; that is, a fantasmatic scenario for resolving the capitalist antagonisms he so aptly described”.

It failed for not being radical enough. Is the movement brave enough to imagine something better, that is not in itself a reproduction of capitalist/colonialist fantasy? At this point, we may not be able to imagine that better something – in fact, Zizek insists that it may be impossible – but even the mythical nature of decolonisation must drive us towards revolutionary resistance of the prevailing system.

Imagination is the core property of the decolonisation movement. To fail at it is to fail the movement. Author Thando Mgqolozana is on this path in his conceptualisation of decolonisation of the literary landscape not as a transformation, but as a complete break with the past.

In explaining why his new Khayelitsha Book Fair was so necessary, he told Redi Tlhabi in a radio interview: “Because the literary landscape that we have was formed not with black people in mind, and it is now being maintained not with black people in mind. Black people are excluded from it. I see no reason for us to beg to be integrated into this system.”

Mgqolozana continued: “We need a new think, not to modify what we have but to start a whole new thing that is not framed by concepts of colonialism.” – Sipho Hlongwane